The crew of the Sikorsky S-76A — dispatched to pick up a seriously ill child from a remote town in Northern Ontario, Canada — was “not operationally ready” for a visual flight rules (VFR) departure from Moosonee, Ontario, Canada, into total darkness, the Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) says. The emergency medical services (EMS) helicopter crashed after takeoff, killing its two pilots and two paramedics and destroying the helicopter.

Neither pilot possessed “the necessary night- and instrument-flying proficiency to safely complete this flight,” although both were qualified according to regulations, the TSB said.

Nevertheless, the causes of the May 31, 2013, accident “went well beyond the actions of this flight crew,” the TSB added, pointing to actions by the regulator, Transport Canada (TC), and the operator, Ornge Rotor-Wing (RW), which provides air medical transportation from seven rotary-wing and three fixed-wing bases throughout Ontario.

The TSB said the pilots “had not received sufficient and adequate training to prepare them for the challenges they faced that night,” and the operator’s standard operating procedures did not specifically discuss the hazards of night operations. In addition, “insufficient resources and inexperienced personnel in key positions … led to some company policies being bypassed and, ultimately, a suboptimal crew pairing that night.”

The TSB’s final report faulted TC for “inconsistent and ineffective surveillance” of the operator.

TC knew that Ornge RW “was struggling to comply with regulations and company requirements,” the TSB said. However, “despite clear indications that Ornge RW lacked the necessary resources and experience to address issues that had been identified months before the accident, TC’s approach to dealing with a willing operator allowed non-conformances and unsafe practices to persist.”

Emergency Evacuation

The departure at 0011 local time came about five hours after Ornge RW first received a request for the emergency evacuation of a young patient from Attawapiskat, Ontario; the helicopter would have been flown from Moosonee to Attawapiskat to pick up the patient, and then from Attawapiskat to Moose Factory. The first request — at 1900 local time May 30 — was turned down because of poor weather in Moosonee, as was a second request at 2009.

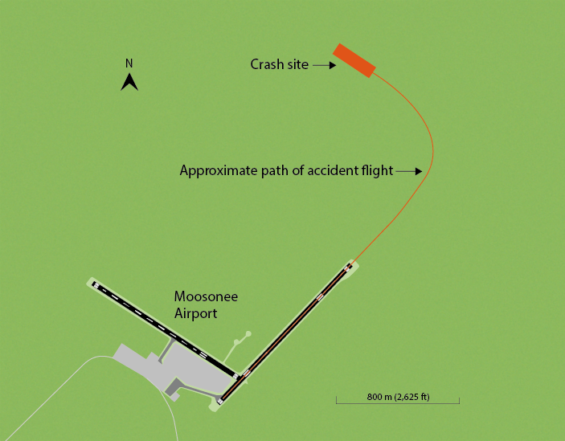

At 2319, however, the captain told the Ornge Operations Control Centre that weather conditions had improved, and he accepted the trip. The helicopter was fueled for the 108-minute VFR flight, and the pilots began the pre-start checklist at 0000. After takeoff, as the helicopter climbed through 300 ft above ground level (AGL), the first officer, who was the pilot flying, began a left turn, and the crew began post-takeoff checks.

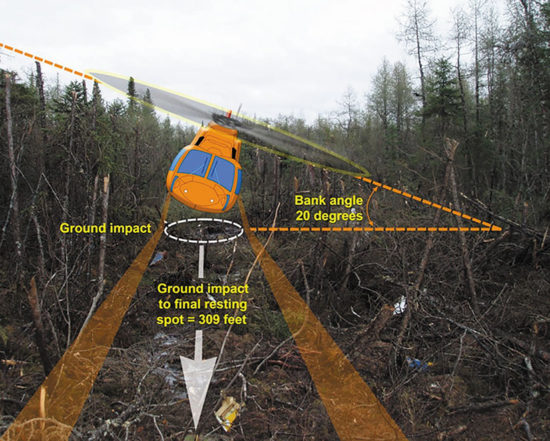

The captain called “30 degrees of bank,” and the first officer’s response “indicated that it was too much bank, and [he] apologized,” the report said. “One second later, the landing-gear warning horn sounded; the captain advised that they were descending and said, ‘Let’s climb.’ The aircraft struck terrain less than one second later.”

The crash came 23 seconds after the first officer had said he was beginning the left turn.

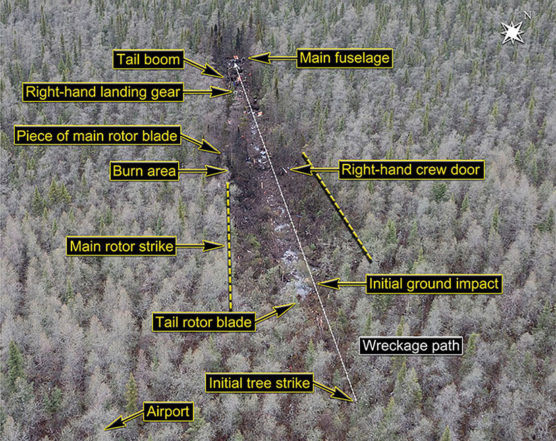

The burned wreckage was found several hours later in a thickly wooded, swampy area about 1 mi (2 km) from the runway.

Working While Vacationing

The captain held an airline transport pilot license–helicopter, with nine type ratings, including one on the S-76; he also was a licensed maintenance engineer. He had 11,500 flight hours, including 10,800 hours in helicopters, 150 hours as pilot-in-command in the S-76A, 650 hours at night and 244 total instrument flight hours.

He was working as a part-time pilot for Ornge RW while on vacation from his full-time job as chief pilot of the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (MNR) Rotor-Wing division — and periodically had done similar part-time work since 2001, when he completed his S-76A initial aircraft type course.

MNR helicopter flights were conducted predominantly as day VFR flights, although night VFR flights also were offered. In 2005, the MNR began using night vision goggles (NVGs) on all planned night VFR flights and on some other night flights, provided the NVGs were available and the pilots were trained and current in NVG use. The accident captain was described as instrumental in implementing NVG use at the MNR. Ornge RW had considered introducing NVGs but, largely because of cost, had decided against such a move, the report said.

Although the captain had flown to or from Moosonee on “a few” flights while at MNR and in his previous EMS work, there was no record that he had flown out of Moosonee as pilot-in-command on a night VFR flight “since at least 2001, when he first began flying as an EMS pilot,” the report said.

In 2008, he completed a pilot proficiency check (PPC) in an S-76A and received a score of 2 on a four-point scale for pilot not flying duties, the report said; citing TC’s Pilot Proficiency Check and Aircraft Type Rating Flight Test Guide (Helicopter).1 The guide said the score signified compliance with the “basic standard” but that “major deviations from the qualification standards occur, which may include momentary excursions beyond prescribed limits but these are recognized and corrected in a timely manner.”

The pilot joined Ornge RW in March 2013, briefly as a first officer because of his limited recent experience in night and instrument flight rules operations but ultimately as a captain. His training record included an entry by an S-76 line captain indicating that he had undergone “no training to date” in black hole operations. However, the chief pilot told accident investigators that he “believed that the training had been completed in the simulator,” the report said.

His first shifts with Ornge RW were all-day shifts (0700 to 1900) on a rotation from April 25 to May 4, 2013. The accident flight occurred during the second rotation, which began May 23. He worked days for the first week of that rotation, and his first night shift was from 1900 May 30 to 0700 May 31, working with the first officer involved in the accident.

“This was their first night shift together, and aside from the five night takeoffs and landings completed during simulator training at the end of March 2013, it was the captain’s first night flight at Ornge RW,” the report said. “At the time of the occurrence, the captain had flown approximately 28 hours on the S-76A since joining Ornge RW in March 2013.”

During most of his second rotation at Ornge RW, the captain had been “heavily involved with MNR business,” the report said, noting, for example, that on one day, he participated by telephone in a 45-minute MNR managers’ meeting and sent more than 50 emails — many of them related to MNR — between his four Ornge RW flights.

In the hours before the accident night shift began at 1900 May 30, the captain again filed a number of MNR-related emails and participated in another MNR telephone conference, from 0900 until 1215. The report noted that, although MNR had consistently approved the captain’s requests to conduct EMS flights during his vacation time, MNR employees were not aware that he was at Moosonee Airport during the teleconference.

The captain typically napped before night shifts, and investigators said it was “highly likely” that he had done so during the afternoon before the accident flight. There was no indication that fatigue played a part in the accident, the report said.

The captain’s logbook showed that, other than the instrument flight rules (IFR) portion of his recurrent S-76 training in March, he had conducted no IFR flights and undergone no IFR training at Ornge RW. Three flights earlier in 2013 were identified as IFR training. The logbook also showed no record of actual or simulated IFR flight between 2011 and 2013, the report said, adding, however, that “there were PPC/IFR entries in December 2012 and April 2013.”

The first officer held a commercial helicopter pilot license with endorsements for the S-76 and four other helicopter types. He had 3,700 flight hours, all in helicopters, including 158 hours in S-76s, 140 hours at night and 33 hours in actual or simulated instrument meteorological conditions. He completed his training with Ornge RW in September 2012.

A post-accident review of his records showed that he had conducted two night takeoffs and landings in the 90 days before the accident, and a total of 10 night takeoffs and 11 night landings during his time at the company. Because of his limited night flying experience, he typically performed pilot monitoring duties while the captains flew the helicopter, the report said.

“Company employees considered the first officer to be highly proficient in daytime VFR operations,” the report said. “However, he had previously encountered some difficulties at night.”

The report cited “a night departure into a black hole in early March 2013, [during which] the first officer began turning at 300 feet AGL. The captain intervened, applied collective thrust and directed the first officer to continue climbing straight ahead up to at least 500 feet AGL. … The captain of the flight had anticipated that the first officer would have difficulties because of his inexperience in night black-hole operations, and therefore did not consider it necessary to report this.”

The accident helicopter was manufactured in 1980 and registered as a commercial helicopter at Ornge RW in 2012. It had accumulated 15,600 flight hours at the time of the accident, and 48,400 landings. It was certified, equipped and maintained in accordance with regulations and there was no indication of any malfunction during the accident flight.

Limited Ambient Lighting

Transportation Safety Board of Canada

At the time of the accident, weather conditions at Moosonee Airport included winds from 40 degrees at 5 kt, visibility of more than 9 mi (14 km), scattered clouds at 4,600 ft above mean sea level and an overcast ceiling at 9,000 ft. About 50 percent of the moon was illuminated, but, the report noted, ambient lighting would have been reduced because of the overcast.

Few visual cues are present off the departure end of Moosonee’s Runway 6, the report said.

“Exacerbating this situation on the night of the occurrence was an overcast ceiling, which would have limited the ambient lighting available to provide a visible horizon or other visual cues necessary to maintain orientation” the report said. “Hence, the crew conducted a flight under night VFR regulations without sufficient ambient or cultural lighting to maintain visual reference to the surface. As a result, the occurrence pilots would have required complete reference to flight instruments to maintain control after passing the end of the lit departure runway.”

The investigation concluded that Ornge RW lacked standard operating procedures (SOPs) that would have addressed hazards associated with night flight operations. (Other SOPs applied to designated black-hole locations, but Moosonee was not among those airports.)

The lack of appropriate SOPs contributed to the accident, the report said.

The report also cited other problems in the company’s operations, including that it:

- Was not using a currency-tracking program designed to ensure that pilots were qualified “in accordance with both company and regulatory night flight currency requirements.” As a result, company schedulers “did not identify that … the first officer was not qualified for the flight.”

- “Bypassed and eroded” its own policies and procedures that defined a pilot’s operational readiness. This “resulted in the crew not being operationally prepared for the conditions encountered on the night of the occurrence.”

- Operated “with insufficient and inexperienced personnel in key positions, which allowed unsafe conditions to persist.”

The TSB noted that Ornge RW had eliminated pilot manager positions at each base in 2012, when it began using a centralized scheduling system. The change meant that “knowledge of local operating areas and crews thus was no longer considered when scheduling crews,” the TSB said, adding that because little consideration was given to pilot experience or proficiency, “the company did not recognize the risks associated with pairing the occurrence pilots together on a mission that they were not operationally ready to conduct.”

The report also criticized TC’s handling of oversight activities, which “did not lead to the timely rectification of non-conformances that were identified, allowing unsafe practices to persist.” The report added that the training provided to TC inspectors “resulted in uncertainty, which led to inconsistent and ineffective surveillance of Ornge Rotor-Wing.”

In the year before the accident, TC had repeatedly identified non-conformances involving the company’s pilot training program and did not modify its oversight methods when the problems persisted, the report said.

In a January 2013 inspection, TC identified the heavy workload for the Ornge RW operations manager and chief pilot, noting that several key positions were vacant when the accident occurred and that other manager posts had been eliminated.

“As a result, many safety-related tasks went either incomplete or were not started, including the rectification of training-related problems; support for pilot trainees; tracking/verification of training records, pilot qualifications and pilot currencies; updating and approving company SOPs and company publications; and hiring more staff,” the report said. “As a result of these staffing challenges, unsafe conditions persisted, with the ultimate result that the company was not ensuring that its pilots were qualified and adequately prepared for operational duty.”

The report also cited TC’s delay in mandating implementation of safety management systems (SMS) by smaller aircraft operators while maintaining an oversight philosophy that presumes all operators can identify safety deficiencies and rectify them.

Aftermath

In the aftermath of the accident, Ornge RW implemented dozens of related safety actions, including the adoption of new restrictions for all night takeoffs and departures, and new procedures for flight in black-hole conditions; prohibitions of turns that exceed standard-rate turns in night and IFR operations; creation of a program to monitor and document “all necessary steps in a first officer’s progression; and the study and subsequent adoption of plans calling for the use of night vision goggles in night VFR operations.

The TSB issued 14 safety recommendations, including one that calls on TC to “clearly define the visual references” required to reduce the risks associated with night VFR flight and another that calls for instrument currency requirements “that ensure instrument flying proficiency is maintained by instrument-rated pilots who may operate in conditions requiring instrument proficiency.”

In addition, TC should establish PPC standards that “distinguish between, and assess the competencies required to perform, the differing operational duties and responsibilities of pilot-in-command versus second-in-command”; require all commercial operators to implement a formal SMS, assess those SMSs regularly and enhance its oversight policies to “ensure the frequency and focus of surveillance, as well as post-surveillance oversight activities, including enforcement, are commensurate with the capability of the operator to effectively manage risk,” the report said.

This article is based on TSB Aviation Accident Investigation Report A13H0001, “Controlled Flight Into Terrain; 7506406 Canada Inc.; Sikorsky S-76A (Helicopter), C-GIMY; Moosonee, Ontario; 31 May 2013.” 2016. Available at <www.tsb.gc.ca>.

Note

- TC. TP 14728, Pilot Proficiency Check and Aircraft Type Rating Flight Test Guide (Helicopter), First Edition (November 2007).

Featured image: © TimesEditrtor CC-SA 3.0 | Wikimedia