So few pilot weather reports (PIREPs) are filed during overnight hours that the U.S. National Weather Service (NWS) has difficulty developing accurate weather advisories, the U.S. National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) says.

The scarcity of PIREPs — not only overnight but also around the clock — has factored in a number of accidents, the NTSB said in a report made public in late March, citing investigations of 16 accidents and incidents between March 2012 and December 2015 that revealed “PIREP-related areas of concern.”

“Pilots are providing relatively few PIREPS, particularly during good or as-forecasted conditions, and air traffic controllers are not consistently soliciting PIREPs during weather conditions that mandate such services,” the report said. “Also, pilot assessments of weather conditions are subjective, and submitted reports can be inaccurate or incomplete.”

The scarcity of overnight PIREPs might be remedied, in part, if the Cargo Airline Association — whose members include some of the largest cargo air carrier operators, which conduct extensive overnight operations — would encourage its members to provide more reports, according to the NTSB, which included such a recommendation in the report.

PIREPs typically are submitted verbally, over the cockpit radio, to air traffic controllers; flight service station (FSS) personnel; or company dispatchers, flight coordinators or other company personnel, the report said, noting that smaller numbers are sent electronically using aircraft equipment or web-based tools.

After a PIREP is submitted, the person who receives it enters the information into a standard format set up by the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA); if a PIREP is submitted electronically, the information is encoded in the required format. From that point, the PIREP is made available to other users of the National Airspace System (NAS) — pilots; air traffic control (ATC) personnel, who consider weather in organizing the flow of traffic in the areas for which they are responsible; and NWS meteorologists, who consider PIREPs in developing aviation weather forecasts and advisories.

“PIREPs, because they provide in situ observations, are one of the most important pieces of information weather forecasters have when assessing the quality of their forecasts and improving graphical weather products used by pilots and others in the NAS,” the NTSB report said.

Nevertheless, the document added, “For PIREPs to be most effective, they must be numerous, accurate and made available quickly in the NAS.”

When those conditions are not met, the result can be delays, errors and loss of information.

“These types of issues — because they affect the accuracy and timeliness of the weather information upon which flight safety decisions are made — can play a role in the complex interaction of events and conditions that lead to aircraft accidents and incidents,” the report said.

The NTSB report described an analysis of a number of accidents and incidents and a series of discussions with PIREP users that revealed “deficiencies in the handling of PIREP information that resulted in delays, errors and data losses” — issues that can result in accidents.

“Complete, accurate and timely weather information is essential to support flight safety for all aircraft operations, large and small, in the NAS,” the report said. “It is vital for use in avoiding inadvertent encounters with hazardous weather and preventing weather-related accidents.”

Air carrier encounters with in-flight turbulence account for most injuries to passengers and flight attendants, and general aviation accidents with weather-related poor visibility typically have higher fatality rates than other types of accidents, the report added.

Improvements in Forecasting

The report characterized an overall improvement in weather forecasting over the past 10 to 20 years, largely as a result of increases in observed data from surface weather-reporting stations. No similar increase has occurred for weather conditions aloft, the report said.

Pilots have said that PIREPs are important in their flight planning, but although they appreciate the reports filed by other pilots, relatively few submit PIREPs themselves, the report said.

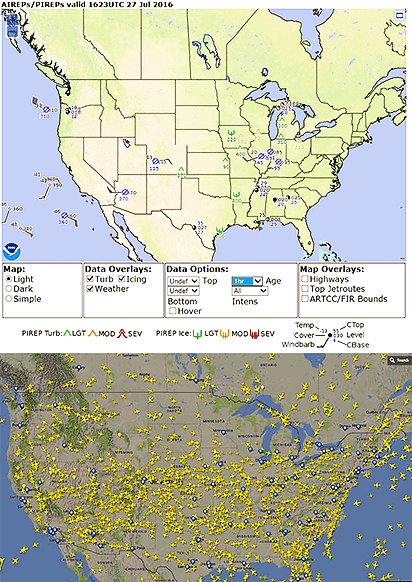

The report cited both a 2016 survey by the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association (AOPA),1 which found that, of 700 respondents, 83 percent said they considered PIREPs extremely or very important to aviation safety, as well as 2010 research2 that determined that U.S. pilots across the nation submitted, on average, 90 PIREPs per hour — representing only a small fraction of the number of flights in the air. Figure 1 illustrates the significance of these numbers, with a graphic comparison of the two dozen PIREPs submitted in an unspecified one-hour period and the volume of air traffic in the NAS during the same hour.

According to the report, pilots have a variety of reasons for not routinely filing PIREPs.

Some are unaware of the importance of PIREPs, especially those that reaffirm conditions described in the forecast and those that reflect fair weather, the report said, noting that the 2010 research found that many pilots believed PIREPs were designed for reporting bad weather. The AOPA survey found that 81 percent of pilots said they would “rarely to never” submit a report if conditions were as-forecast and 76 percent said they would rarely to never report “benign conditions.”

The report quoted an official at the NWS Aviation Weather Center as saying that PIREPs describing good weather are just as valuable as those that report poor conditions; PIREPs of good conditions can help air traffic controllers identify areas where they can safely route traffic and help them refine weather forecasts.

The report concluded that some pilots “find the process [of filing a report] too time consuming and therefore choose not to submit PIREPs.”

Other reasons for the scarcity of PIREPs may be that some pilots lack confidence in their ability to assess weather conditions or to use the PIREP format to submit the report, that the concept of submitting PIREPs was never emphasized during training and that they are reluctant to interrupt other flight duties, the report said. In addition, some pilots may fear enforcement action if they file a PIREP that makes clear they have had an inadvertent encounter with weather conditions in which they are not permitted to fly or their aircraft is not certificated to operate.

“Given that weather-related accidents have the highest fatality rate in [general aviation], it is unfortunate that pilots might withhold critical safety information based on enforcement fears,” the report said. “The consequences of even one unreported icing or low-visibility encounter in a mountain pass could be deadly.”

The report cited a PIREP filed by the pilot of a Cessna 180 who said he was returning to his departure airport because he could not keep the airplane in visual meteorological conditions.

“This information was potentially life-saving to other pilots and helpful to weather forecasters, particularly if the conditions were unexpected,” the report said. “Because of the importance of such hazardous-weather PIREPs, the NTSB believes that enforcement fears that could deter such reports need to be addressed.”

Reporting Errors

The NTSB study noted errors and inconsistencies in PIREPs, including one event involving a PIREP submitted by the captain of a Bombardier CL-600 that flew into turbulence in McCook, Nebraska, in June 2015. The location, altitude and time of the encounter differed from the information in the PIREP, which was distributed to the NAS.

“The captain notified both company dispatch (via ACARS [the aircraft communications addressing and reporting system]) and ATC of the event location, but, due to the immediate need to first fly the aircraft, request course deviations and assess the status of the passenger injuries, he could not recall the exact timing of when he made the notifications,” the report said. “The inaccurate PIREP, which differed from the actual weather encounter by more than 140 miles [225 km], 1,000 ft of altitude and about 20 minutes, had no value in potentially helping other pilots tactically avoid the area of turbulence or for helping meteorologists verify their forecasts or issue advisories.”

The report noted that 2013 research, which compared human-submitted PIREPs with automated data, found that human reports contained errors of distance that ranged from 22 to 28 mi (35 to 45 km).

“Weather researchers rely on accurate time, location and FL [flight level] information to avoid introducing errors that directly affect the weather products that NAS users rely on daily,” the report said. “Although on-board technology … can help capture time, location and altitude information, pilots must be diligent in accurately noting and reporting these for observed weather phenomena.”

Other PIREPS have lacked essential information, including whether an encounter with low level wind shear (LLWS) resulted in an increase of airspeed or a decrease, and whether the encounter occurred in clouds, the report said, adding, “These types of omissions make it more difficult for meteorologists to validate LLWS forecasts, particularly at airports for which a PIREP is the only source of LLWS information.”

In some cases, reporting criteria for specific weather phenomena — such as mountain wave activity, which can result in flight safety hazards in the form of large excursions from assigned airspeed and/or altitude — are unclear or nonexistent, the report said.

As an example, the report cited a PIREP filed by a Boeing 757 pilot, who reported that mountain wave activity caused airspeed changes ranging from plus 20 kt to minus 40 kt. As distributed, the PIREP classified the encounter as “turbulence” of “light” intensity, even though the event “involved large and potentially hazardous effects on airspeed.”

Dissemination Errors

Noting that a PIREP has value only if it can be made available quickly to others in the NAS, the report said that the NTSB study found that PIREP dissemination has been impeded by “procedural, workload, data-capturing and distribution issues.” These problems also have introduced inaccuracies into PIREP information.

Problems with dissemination may lie with air traffic controllers, who are responsible for relaying PIREPs to other ATC personnel, FSS specialists and other military and civil facilities.

As an example, the report said that the NTSB investigation of a February 2015 accident found that the Fort Worth, Texas, air route traffic control center (ARTCC) “did not disseminate … PIREPs described as ‘containing no significant weather information.’ This is unfortunate, given that a meteorologist at the CWSU [center weather service unit] associated with the Fort Worth ARTCC stated that null PIREPs are important for the CWSU’s work.”

The report noted that the NTSB has investigated cases “in which PIREP handling was inconsistent with good judgment and/or not in compliance with procedures.” For example, the report cited the NTSB investigation of an August 2015 event in which an Airbus A320 flight crew declared an emergency after an en route encounter with hail shattered the windshield and caused airframe damage.3

“The investigation discovered that the company dispatcher did not provide the flight crew with the most current turbulence and thunderstorm activity information that had been issued by the airline, both of which indicated potential thunderstorm activity along the route of flight,” the report said. The information was not provided even though the flight crew had asked the Denver ARTCC controller “repeatedly” about a so-called hole in a line of convective weather.

The relevant PIREPs included “a report from the crewmember of a Boeing 737 who had just transited the gap between thunderstorms and advised that he ‘wasn’t sure if anyone was going to want to go through there behind us’ and from a crewmember of another transport-category airplane who had flown through the gap between the two areas of thunderstorms and advised the controller to ‘let the guys behind us know that … our computer’s thinking we’re falling out of the sky.’”

A PIREP for the encounter with hail was coded as routine, even though it met the criteria for an urgent PIREP, the report said. The misclassification resulted in a delay of PIREP dissemination, the report said.

Data Entry Errors

Data-entry errors such as the miscoding of urgent PIREPs as routine are common, the report said, adding that other similar mistakes involve typographical and formatting errors. These mistakes typically are made by ground personnel, but as pilot use of data-input systems increases, the number of errors made by pilots also is increasing, the report said.

The errors can limit a PIREP’s usefulness, the report said. The Aviation Weather Center website, for example, cannot process a PIREP containing these errors, and they might not be distributed to NAS users.

The report noted that formatting errors have prevented dissemination of some PIREPs, including one that reported a funnel cloud.

Proprietary Practices

In some cases, pilots file PIREPs not to ATC or FSS but to company dispatchers or other company personnel. Some of these reports are shared with the NAS, but other operators consider the PIREPs proprietary information to be shared only within the company.

The report cited the NTSB investigation of a July 2015 accident near Juneau, Alaska, in which investigators found that flight coordinators working for two competing operators did not share company PIREPs with the NAS.

“Both of these operators provide air service to remote areas that have relatively few weather observation sources,” the report said. “Therefore, PIREPs from these operators would be valuable not only to other pilots for avoiding weather hazards but also to weather forecasters for issuing advisories and improving forecasts in areas that have few observation stations.”

“Both of these operators provide air service to remote areas that have relatively few weather observation sources,” the report said. “Therefore, PIREPs from these operators would be valuable not only to other pilots for avoiding weather hazards but also to weather forecasters for issuing advisories and improving forecasts in areas that have few observation stations.”

Some companies, however, have “gone to great lengths” to share PIREP information with other operators, the report said, singling out United Airlines, which developed a computer processor and interface to collect and disseminate PIREPs, and Southwest Airlines, which included requirements for sharing PIREP information in company manuals.

The report concluded that pilots who learn during initial training how to file PIREPs are more likely than those who do not to routinely submit reports, and that pilots can be encouraged to file more frequent PIREPs if they are educated about the safety impact of the reports.

The NTSB also said that PIREP information should be shared “without exception to operator or weather service provider” and that an effective automated system for submitting the information would improve the quantity of PIREPs available to all users of the NAS.

Safety Recommendations

Along with the call for cargo pilots to increase their filing of overnight PIREPS, the report contained 18 additional safety recommendations, most of which were addressed to the FAA, including several recommendations for streamlining the process by which PIREPs can be submitted and for developing information to emphasize the importance of hazardous-weather PIREPs.

Other recommendations urged the FAA to work with the National Air Traffic Controllers Association to develop guidelines for all types of ATC facilities for soliciting and disseminating PIREPs, and to work with the NWS to revise guidelines for reporting several types of weather conditions, including LLWS and mountain wave activity.

Among other recommendations were calls for flight instructor organizations to teach all students the importance of filing PIREPs.

This article is based on NTSB Special Investigation Report NTSB/SIR-17/02, “Improving Pilot Weather Report Submission and Dissemination to Benefit Safety in the National Airspace System.” March 29, 2017.

Notes

- NTSB. “PIREPs: Pay It Forward … Because Weather for One is Weather for None.” Transcript of Forum, Day 2 (June 22, 2016). Washington. Cited in NTSB/SIR-17/02.

- Casner, Stephen M. “Why Don’t Pilots Submit More Pilot Weather Reports (PIREPs)?” The International Journal of Aviation Psychology Volume 20 (4): 347–374. Cited in NTSB/SIR-17/02.

- NTSB. Incident Report OPS15IA020. None of the 124 people in the airplane was injured, and damage to the A320 was characterized as minor. The NTSB said the probable cause of the accident was the flight crew’s “continued flight into a closing gap between areas of thunderstorm activity and their failure to maintain the required lateral separation from the thunderstorms, which resulted in the airplane’s encounter with hail and subsequent airplane damage.”

Featured image: © WestWindGraphics | iStockphoto

Figure 1: U.S. National Transportation Safety Board

Screenshot: U.S. National Transportation Safety Board