In 90 commercial jet evacuations from 1961–2011, on average about half the available exits were used, and in only one case were all the available exits used. Those were among the findings presented by Fons Schaefers of SGI Aviation at the 2nd International Cabin Safety Conference in Amsterdam, Netherlands, in October.1

“All these accidents were survivable but life-threatening because of fire or submersion in water,” Schaefers said. “In situations requiring urgent evacuation, exits can make the difference between life and death. But how often are exits used in such critical situations?”

Surprisingly few attempts have been made to analyze exit usage in relevant accidents, he said. The Amsterdam presentation was an update of a similar presentation given in 1994, adding data from 1993–2011.

Accidents meeting the criteria for inclusion in his latest study database totaled 150.2 Of those, the reports for about 90 accidents included enough information to draw useful conclusions concerning exit usage. In 51 of the 90 accidents, the number of evacuees for each exit was known; in 39, data showed only which exits were used and not how many evacuees they served.

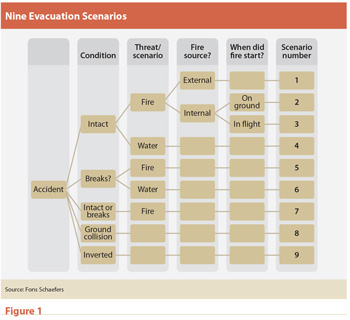

Various criteria can be present or absent in accidents in which evacuation is required. To clarify exit usage under different conditions, the accidents were grouped into nine scenarios (Figure 1). In addition, exits were numbered according to location, both for aircraft with wing-mounted engines (Figure 2) and those with fuselage-mounted engines (Figure 3).

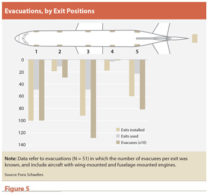

The number of evacuees per exit was known in only some of the accidents in each scenario. Because the known-to-unknown ratio varied among scenarios, the numbers of evacuees per exit may suggest differences but are not directly comparable. By the same token, not all aircraft have the same number of exits, so differences in usage do not necessarily indicate the efficiency of an exit position.

Scenario 1: Land — Intact — External Fire

This was the most common scenario, representing 42 of the 150 accidents in the database. In this type of accident, the aircraft came to rest on its landing gear, fuselage or a combination. “Intact” refers to the condition of the fuselage.

The overall exit usage rate was about 50 percent. Location 1, the farthest forward, was most used for evacuation in this type of accident.

Scenario 2: Land — Intact — Internal Fire Started on the Ground

This scenario led to seven evacuations. The overall exit usage rate was about 70 percent, with location 1 most commonly used, followed in frequency by location 3.

Scenario 3: Land — Intact — Internal Fire Started in Flight

Only four accidents in the database met the criteria for this scenario. These accidents had a “high fatality rate,” Schaefers said. “Only forward [location 1] and overwing [location 3] exits were used.”

Scenario 4: Water — Intact

Ten of the accidents were included in this category, and the exit usage rate was relatively high at 70 to 100 percent for all exits other than the tail.

Scenario 5: Land — Breaks — External Fire

This is the first scenario in which the fuselage broke into two or more sections, providing additional exit possibilities beyond the standard exits — in some cases occupants were ejected or extricated by rescue personnel through the breaks.

It was a relatively common scenario, comprising 40 accidents of the 150 in the database.

“In absolute numbers, position three scored highest in scenario 5,” Schaefers said. “However, although not that many aircraft have exits in positions 2 and 5, position 2 actually had the highest ‘usage rate’ of about 65 percent, position 5 had a rate of about 45 percent and the rest were lower.”

Scenario 6: Water — Breaks

In this scenario, also one in which the fuselage breaks up, the overwing exits — position 3 — had a high percentage of use. Position 2 was also used often. The other positions scored low.

Scenario 7: Land — Intact or Breaks Unknown — External Fire

This scenario accounted for the third highest number of accidents, 32. In 29 of those, however, the exit usage was unknown, thereby limiting analysis.

Two other scenarios included 8, “Ground Collision — External Fire” and 9, “[Fuselage] Inverted,” both rare enough to preclude significant findings about exit usage.

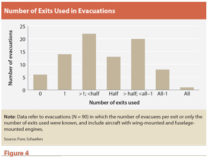

Besides the overall finding that an average of half the available exits were used, Schaefers reported that in six cases where exits were usable, no evacuation took place or only fuselage breaks were used for escape. In the greatest number of accidents, more than one but fewer than half the available exits were used (Figure 4).

Tail exits are only used on older aircraft types. Of 27 evacuations of aircraft equipped with a tail exit, that exit was only once used successfully. “In most cases, it was not used, but in two cases, passengers and crew became trapped and had to be extricated by rescue personnel,” Schaefers said. “This was not always successful and people have died as a result.”

Subdividing the entire 1961–2010 period into decades, it was found that the numbers of evacuation accidents rose in 1971 through 1980, but then decreased and were lowest in the most recent decade — in spite of considerable traffic growth over the whole stretch.

In the survival ratio, or percentage of occupants who survived the accidents, there was little change from decade to decade, more than 70 percent except in 1971–1980.

Most aircraft have the same number of exits on the left and right sides. Did passengers show a bias toward evacuating via the left side, from which they had boarded? It would appear so. In the 51 cases where the data for evacuees per exit were known, 1,847 were directed to or chose exits on the left, compared with 1,555 who used exits on the right.

The presence of fire might have influenced the side chosen for evacuation in some cases. However, in 63 cases involving external fire, there were 13 — 21 percent — in which exits on only one side were used. In only three cases were all the exits on one side used to the exclusion of the other side.

Positions 2, 3 and 5 had high evacuee rates per used exit (Figure 5). Position 1 had a high usage rate when the fuselage remained intact, but it was rarely used in break-up cases. Positions 4 and the tail were virtually unused. “Tail exits have become deathtraps,” Schaefers said, recommending that they not be included in designs.

Schaefers’s analysis included reasons for particular exits not being used. In approximate order of frequency, he said, they included these:

- There was a fire outside.

- The exit was in a destroyed section of the aircraft.

- The door was jammed.

- The exit was obstructed, inside or outside the aircraft.

- The aircraft’s position on the ground or water made the exit unusable.

- Passengers did not understand the use of exits, particularly overwing and tail exits.

Less frequent factors included exits that were out of reach because of a fuselage break, the difficulty or impossibility of opening and then closing an exit, inward door movement impeded by crowding, slide malfunctions and submersion in water.

To sum up, Schaefers said that generally, exit use depends on the accident scenario. “In light impact cases with external fire and all cases of internal fire, forward exits are most ‘popular,’” he said. “Where there has been a heavy impact, rear exits are most often used, sometimes supplemented by breaks. In water scenarios, overwing exits are most used.”

His recommendations included the following:

- “Exits should be installed in opposite pairs;

- “Exits should be designed so that they can quickly be closed again after opening; [and,]

- “Do not assume exits are not usable on one side because a fire is reported on that side.”

Notes

- Schaefers, Fons. “Exit Usage in Survivable Accidents Under Life-Threatening Conditions.” Proceedings of the International Cabin Safety Conference, 23–25 October 2012.” Portland, Oregon, U.S.: (L/D)max Aviation Safety Group.

- Criteria for inclusion of accidents in the study included the following: jet air transport aircraft; Western-designed; passengers aboard; at least one usable exit; evacuation vital (in hindsight) for life saving; not caused by hostile action. “Evacuations that were precautionary or could be determined retrospectively to have involved no threat to life were excluded,” Schaefers said.