Eurocopter AS350 B2 had been improperly loaded before it struck a snow-covered mountain slope as the pilot attempted to deliver a group of skiers to the top of several ski runs in New Zealand’s Mount Aspiring National Park, the Transport Accident Investigation Commission (TAIC) says.

One of the skiers was killed in the Aug. 14, 2016, accident, after he was trapped beneath the wreckage, and the other six occupants of the helicopter experienced moderate to serious injuries, the TAIC said in its final report, published in December 2017. The helicopter was destroyed.

The TAIC’s investigation identified two safety issues: “that the operator’s standard operating procedures did not require its pilots to routinely calculate the performance capabilities of their helicopters for the intended flights” and “that there was a risk of not knowing an aircraft’s capability when using standard passenger weights, and therefore of pilots operating close to the limits of their aircraft’s performance.”

The report said the accident, along with several others, was “suggestive” of a third issue — that the safety culture experienced by some New Zealand helicopter pilots may include “operating their aircraft beyond the manufacturers’ published and placarded limits, with the possibility that such a culture has become normalised.”

The accident occurred during the helicopter’s fourth heli-ski flight of the morning, conducted in “fine and clear” weather with light variable winds. The helicopter was one of five that the operator, The Helicopter Line, had scheduled to ferry three heli-ski groups to the top of various ski runs between Mount Aspiring and Lake Wanaka.

Earlier in the day, before the heli-ski flights, the pilot left Queenstown in a different AS350 B2 to fly passengers to the Cardrona snow park. He then flew to Wanaka to leave the helicopter with a maintenance organization and departed in the accident helicopter, which had recently been imported from the United States. The accident flight was its first commercial flight in New Zealand.

After checking over the helicopter with a maintenance technician, the pilot flew the helicopter back to Queenstown, where the three groups of skiers were given a helicopter safety briefing before a heli-ski guide loaded the first group of five, and their gear, onto the accident helicopter.

“When the pilot boarded the helicopter, he noted that the passengers in Group A were all males of about medium build,” the report said, adding that the heli-ski guide told the pilot that he did not know how much the passengers weighed and that one passenger told him that although they had not been weighed individually, they each weighed about 85 kg (187 lb).

“The pilot thought this was a reasonable estimate that he would use when calculating his fuel loads for the loaded flights to the high-altitude drop-off points for the rest of the day,” the report said.

The helicopter departed for the Phoebe Creek staging area at 1014 local time, and the pilot fueled the helicopter there, while the passengers were briefed on mountain safety and the plans for the day. When leaving Phoebe Creek, the pilot asked “a smaller member of the group” to sit in the center front seat.

“This was a company procedure to minimise the risk of exceeding the weight and balance limits of the helicopter, and to minimise the risk of a passenger’s arm obstructing the pilot’s use of the collective lever located between them,” the report said.

After fueling, the Group A skiers were boarded and flown to the top of the first ski run, and the pilot returned to the staging area for a flight to deliver Group B to the same drop-off point. He then refueled to about 60 percent of capacity before picking up Group C and flying them to the same point. After that, he flew to the bottom of the run to pick up Group A and take them to a flat ridge near the summit of Mount Alta for their next run.

After fueling, the Group A skiers were boarded and flown to the top of the first ski run, and the pilot returned to the staging area for a flight to deliver Group B to the same drop-off point. He then refueled to about 60 percent of capacity before picking up Group C and flying them to the same point. After that, he flew to the bottom of the run to pick up Group A and take them to a flat ridge near the summit of Mount Alta for their next run.

The report described the wind as out of the south and “nearly calm” as the pilot conducted what he called a “relatively shallow approach” to the flat ridge. When the helicopter was 10 to 20 m (33 to 66 ft) from the landing site, he detected “a bit of a sink” in the descent rate and raised the collective lever.

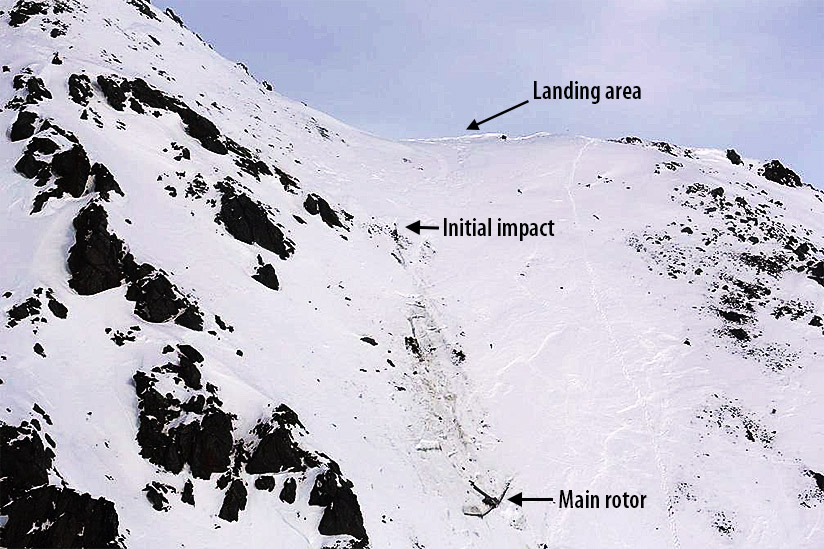

“The guide recalled that the helicopter appeared to be ‘almost stopped’ when it was about 30 m [98 ft] from the site and 2 to 3 m [7 to 10 ft] above it,” the report said. “At that point, the pilot turned the helicopter left, in the direction of his planned escape route, and descended away from the ridgeline. The pilot said that as the helicopter turned downhill, he felt it sink rapidly and unexpectedly. Before he could take any action to arrest the descent, the helicopter struck the side of the slope heavily.”

Five of the seven helicopter occupants were thrown from the fuselage as it rolled 315 m (1,034 ft) down the slope, including one passenger who became trapped beneath the wreckage and later died of his injuries, the report said.

The guide, who had been thrown from the helicopter after his seat belt attachment broke, radioed guides from the other heli-ski groups to inform them of the accident, the report said. The pilot of a company helicopter overheard the radio transmission and initiated the operator’s emergency plan, and within the hour, emergency personnel arrived.

Training in Australia

The 4,176-hour pilot, who began his training in Australia and received a commercial pilot license there in 2002, was issued a New Zealand commercial license in 2005 and joined The Helicopter Line in 2007 as a full-time line pilot. His flight time included about 605 hours in the AS350 and 1,493 hours in the AS355, a twin-engine version of the AS350.

His logbook and company records showed that he had been considered for heli-skiing flights in July 2011 and had completed ground training, but after a subsequent assessment flight “it had been determined that he did not meet the operator’s required standards for heli-skiing flying,” the report said. “During the assessment flight, the instructor had not been comfortable with the pilot’s approaches and considered that he needed more training before he flew heli-skiing operations and that he needed to be re-evaluated for heli-skiing in the future.”

He continued with his regular flying duties, and before the start of the 2012 skiing season, he received additional training and another assessment flight, and was approved for heli-skiing flights with several restrictions that were lifted as he gained experience.

‘High Levels … of Safety’

The Helicopter Line was established in 1986 and grew to become one of the largest helicopter operations in New Zealand. At the time of the accident, it operated 19 AS350s, which it considered “the most suitable type for the range of operations flown in the mountains,” the report said. A company audit conducted in July 2013 by the New Zealand Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) found “high levels of operational safety.”

The accident helicopter was manufactured by Eurocopter (now Airbus Helicopters) in 2004 and had been flown in the United States until it was imported to New Zealand in April 2014. It underwent routine maintenance and had been equipped for heli-skiing flights before its airworthiness certificate was issued on Aug. 15. Its recorded flight time was 3,215 hours. The Arriel 1D1 engine, which had been installed in 2009, had 6,788 hours.

Each of the three front-seat positions (for a pilot and two passengers) was equipped with a four-point harness consisting of a lap belt and two shoulder straps with a single inertia reel. The four rear seats had three-point harnesses, with a lap belt and one shoulder strap, and an inertia reel. The passengers’ harnesses had standard airline-type buckles, which were released by lifting a flap; the pilot’s harness was equipped with a locking mechanism that was lifted before the buckle could be rotated to release the straps.

The accident report said that the two passengers who remained in their seats after the accident had safety belts that were firmly buckled. Of the four passengers who were ejected, one had a buckled, but broken, four-point harness; two — including the passenger who was killed — had unbuckled belts, which the report said probably had been loosely buckled when the impact occurred and subsequently become caught on something and released as the helicopter rolled; and one had a loosely buckled belt. The pilot’s harness was bucked and pulled tight, but he also was thrown from the helicopter.

The report said that after the accident, the operator issued a reminder to staff members that seat belts were to be “snug across the hips” — in a position that reduces the likelihood that they can catch on something and be released inadvertently.

Calculating Weight and Balance

The helicopter’s maximum certified takeoff weight was 2,500 kg (5,512 lb), or, when the load was carried internally, 2,250 kg (4,960 lb). The TAIC calculated that the helicopter was about 30 kg (66 lb) heavier than its maximum permitted weight and that its center of gravity was about 3.0 cm (1.2 in) forward of the limit.

Company operations materials described accepted methods of calculating weight and balance, including one method using a predetermined standard passenger weight; one method placed weight and balance near the limit, but according to the other, the helicopter would have been slightly overweight.

Although a 2005 CAA advisory circular had described the procedure to be used in determining a standard passenger weight, the document also said that “there is no relief provided in the Civil Aviation Rules for an aircraft to operate overweight when using standard passenger weights.” The report noted that Civil Aviation Rules also require compliance with manufacturers’ weight limitations.

“The pilot attempted to manage the loading of his helicopter after he left the base,” the report said. “However, he had no means of weighing the passengers.”

Regardless of how the pilot determined passenger weights, the report said, “it was never going to be possible for him to calculate the helicopter’s longitudinal centre of gravity accurately without the aid of a weight and balance calculator. The risk of inadvertently exceeding the limits was, therefore, too high.”

The first indication that the helicopter was not performing as the pilot had anticipated was “the unexpected slight sink when approaching the landing site,” the report said. “The pilot said that, as he got close to the landing site, he had been focused outside the helicopter, managing the approach path, and had not paid close attention to the airspeed or power demand. He had noticed that he was demanding about 90 percent of the normal operating range before the sink occurred, after which he had immediately initiated his escape manoeuvre. … It was very likely that the helicopter’s speed had reduced below that for translational2 lift, and the power requirement was increasing with further speed reduction.”

The first indication that the helicopter was not performing as the pilot had anticipated was “the unexpected slight sink when approaching the landing site,” the report said. “The pilot said that, as he got close to the landing site, he had been focused outside the helicopter, managing the approach path, and had not paid close attention to the airspeed or power demand. He had noticed that he was demanding about 90 percent of the normal operating range before the sink occurred, after which he had immediately initiated his escape manoeuvre. … It was very likely that the helicopter’s speed had reduced below that for translational2 lift, and the power requirement was increasing with further speed reduction.”

The “slight sink” probably was a result of the helicopter’s movement into an out-of-ground-effect hover, the report said.

The report noted that accident investigators were unable to determine whether the helicopter “was affected to some degree by vortex ring state” — a condition also known as “settling with power,” in which a helicopter loses main rotor lift and the pilot experiences a loss of control. Nevertheless, the report said that vortex ring state was unlikely to have been a significant contributing factor to the accident.

‘High-Risk Activity’

The report characterized heli-skiing as “one of the riskiest types of helicopter passenger operation,” not only because of high altitudes, mountainous terrain and snow-covered landing sites but also because helicopters typically are carrying loads that place them near their performance limits.

“The risk is too high to be relying on standard loading plans with assumed standard passenger weights, when relatively small variations from the standards can put a helicopter outside its published maximum performance capability,” the report said, noting that after the accident, the operator changed its procedures to require calculations of actual weight and balance before every flight.

The report also noted that New Zealand’s helicopter accident rate is higher than accident rates for other sectors and that “there has been public criticism of how helicopters are operated in New Zealand, including a culture of operating outside the manufacturers’ published and placarded ‘never exceed’ limitations. Should this situation exist, there is a possibility that such a culture has become normalised.”

The report said the TAIC has not thoroughly investigated “this potential wider issue” but added that the CAA has begun a review of risk in the helicopter sector. The question of operational culture should be included in that review, the report said.

Note

- TAIC. Aviation Inquiry AO-2014-005, Eurocopter AS350-B2 (ZK-HYO); Collision With Terrain During Heli-Skiing Flight; Mount Alta, Near Mount Aspiring National Park; 16 August 2014. November 2017.

- The report defines translation as the phase of flight “when accelerating from a hover to forward flight or back to a hover.”

All photos: © Transport Accident Investigation Commission of New Zealand

Map: base, © Land Information New Zealand (LINZ) CC-BY 4.0; source, Transport Accident Investigation Commission of New Zealand; inset, © Ridcully Jack | Wikimedia CC-BY-SA 3.0