Despite concern about the risk posed by allowing large lithium battery–powered personal electronic devices (PEDs) to be carried in checked baggage on passenger flights, the International Civil Aviation Organization’s (ICAO’s) Dangerous Goods Panel (DGP) rejected a proposal that would have restricted large PEDs to the passenger cabin unless cargo placement was approved by the operator. Instead, the DGP, meeting in October in Montreal, decided to wait for guidance from the ICAO Council.

In related developments, many of the world’s largest scheduled commercial airlines soon will prohibit passengers from bringing battery-equipped “smart luggage” on board unless the battery is removable and can be carried in the passenger cabin if the luggage itself must be checked. Additionally, the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has released guidance to its inspectors on the use of onboard fire containment devices.

![]() Concerns about the risk of significant numbers of large PEDs being placed in cargo holds in checked baggage were raised in early 2017 after the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) implemented restrictions (the so-called laptop ban) requiring that passenger-carried PEDs larger than a smartphone be carried in checked baggage on flights to the United States from 10 airports in the Middle East and North Africa. The restrictions were subsequently superseded by new enhanced security measures, but the laptop ban revealed a lack of data on the likelihood of a PED entering thermal runaway in a cargo compartment; on the behavior, effects and risks associated with PEDs being placed in checked baggage; and on a lack of specific data regarding the number of large PEDs that passengers were carrying in checked baggage, although it was believed that most passengers carried PEDs in the cabin.1

Concerns about the risk of significant numbers of large PEDs being placed in cargo holds in checked baggage were raised in early 2017 after the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) implemented restrictions (the so-called laptop ban) requiring that passenger-carried PEDs larger than a smartphone be carried in checked baggage on flights to the United States from 10 airports in the Middle East and North Africa. The restrictions were subsequently superseded by new enhanced security measures, but the laptop ban revealed a lack of data on the likelihood of a PED entering thermal runaway in a cargo compartment; on the behavior, effects and risks associated with PEDs being placed in checked baggage; and on a lack of specific data regarding the number of large PEDs that passengers were carrying in checked baggage, although it was believed that most passengers carried PEDs in the cabin.1

So the Fire Safety Branch at the FAA William J. Hughes Technical Center conducted tests to assess potential hazards from the carriage of laptop computers and other large PEDs in thermal runaway in checked baggage. In five of the 10 tests, other dangerous goods, including an aerosol can, permitted to be carried by passengers in checked bags, were packed in suitcases along with PEDs. The results showed that large PEDs packed in checked baggage near an aerosol could produce an explosion and fire that the aircraft cargo fire suppression system in Class C cargo compartments may not be able to safely manage and that the risk in cargo compartments that do not provide the same level of protection as Class C would be even greater.2

The FAA test results were provided to the ICAO Cargo Safety Group (CSG), which was created by ICAO after the initial U.S. security restrictions were implemented to address the potential impact on safety from those security measures. The CSG reviewed the results at its second meeting (CSG/2), which was held in Paris in July. The CSG developed a recommendation for the DGP to amend the ICAO Technical Instructions for the Safe Transport of Dangerous Goods by Air to restrict PEDs to carry-on baggage only unless the operator approved carriage in checked baggage or to restrict large PEDs — those larger than a smartphone — to carry-on baggage only.3

A separate but similar proposal was made by the United States for consideration at the DGP meeting in Montreal, referred to as DGP/26 because it was the 26th meeting of the panel. The U.S. proposal also would have restricted large PEDs to carry-on baggage unless cargo carriage was approved by the operator.4 “Although there was a lack of data to accurately assess the likelihood of a thermal runaway event involving PEDs in checked baggage, it was suggested the potential for this to lead to a catastrophic event could not be ignored. Alternative mitigating measures were considered, but it was concluded that the only feasible measure would be to require large PEDs to be carried in the cabin,” according a summary of the discussion in the DGP/26 final report.

But that argument did not win the day. “The majority of panel members did not consider the proposals mature enough to adopt. They believed further analysis was needed with respect to the likelihood of an event occurring in the cargo compartment and questioned whether the conclusions remained valid, since the security measures that had prompted the need for analysis were no longer in place. They also questioned the feasibility of implementing a prohibition on PEDs from checked baggage and managing approvals to carry them in checked baggage.”

Still, some DGP members believed the potential for a catastrophic event, even if the likelihood was remote, necessitated immediate action. They also believed that, because the CSG developed its recommendations through consensus, action was required.

In the end, the DGP members decided to wait for guidance from the ICAO Council, which is expected to review the CSG/2 report in the near future. Also, as an appendix to the 307-page DGP/26 final report (Appendix D to Report on Agenda Item 6), the panel attached a list of the arguments for and against prohibiting large PEDs in checked baggage.

Smart Luggage Restrictions

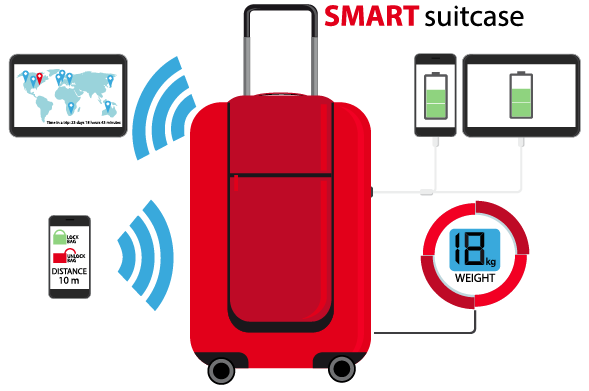

During DGP/26, the panel also addressed so-called smart luggage — bags that come equipped with lithium ion batteries. The batteries in smart bags power the electronic lock, bag-weighing and global positioning system features of many smart bags, but the batteries also are used for recharging personal electronic devices, like smartphones, laptops and tablets. Because the batteries are used to charge other devices, they are considered spares or power banks.

According to the DGP/26 final report, “there were concerns that luggage containing power banks would be checked in, despite the fact that the Technical Instructions required articles whose primary purpose was to provide power to another device to be carried as spare batteries and would therefore be restricted to the cabin.” The DGP agreed to amend the Technical Instructions to require that power banks be removed from bags to be checked and carried in the cabin in accordance with the provisions relating to spare batteries. The amendment also included recommendations for smart luggage to be designed to allow the power bank to be removed by the user and for the power bank to be marked with a Watt-hour rating.

According to the DGP/26 final report, “there were concerns that luggage containing power banks would be checked in, despite the fact that the Technical Instructions required articles whose primary purpose was to provide power to another device to be carried as spare batteries and would therefore be restricted to the cabin.” The DGP agreed to amend the Technical Instructions to require that power banks be removed from bags to be checked and carried in the cabin in accordance with the provisions relating to spare batteries. The amendment also included recommendations for smart luggage to be designed to allow the power bank to be removed by the user and for the power bank to be marked with a Watt-hour rating.

The amendment, unless disapproved by the Council, will take effect with the 2019–2020 version of the Technical Instructions.

The International Air Transport Association’s (IATA’s) Dangerous Goods Board has decided essentially to enact the DGP restrictions a year early. Effective Jan. 15, bags equipped with a lithium battery will only be accepted for carriage on IATA member carriers if it is possible to remove the battery from the bag. “Baggage where the lithium battery cannot be removed is forbidden for carriage” on IATA member airlines, according to an IATA spokesman. Bags with the battery installed must be transported as carry-on luggage. If a smart bag is to fly as checked baggage, the battery must be removed and carried in the passenger cabin.

Smart bags often are built to a size suitable for carry-on baggage, but can end up being checked on crowded flights or on flights operated with aircraft with smaller overhead bins.

Fire Containment Devices

Prompted by queries from its Flight Standards District Offices and its certificate management office, FAA issued guidance to its aviation safety inspectors in early December on the use of commercially available fire containment devices by carriers. According to FAA, at least four air carriers have installed fire containment kits or bags on their aircraft in the past two years. The kits, which usually include a containment bag, sleeve or box, may or may not also come with additional tools, such as a fire gloves, a pry bar or a face protection shield, FAA said.

![]() FAA reminded its inspectors that, despite what manufacturers of these products may say in their marketing materials about their product being “FAA certified” or “meets FAA standards” or “successfully tested by the FAA,” there are no FAA test standards for these containment products, “nor is there a mechanism in place for the approval of these products.”

FAA reminded its inspectors that, despite what manufacturers of these products may say in their marketing materials about their product being “FAA certified” or “meets FAA standards” or “successfully tested by the FAA,” there are no FAA test standards for these containment products, “nor is there a mechanism in place for the approval of these products.”

FAA said it has no objection to the use of the various containment products, provided that procedures in FAA guidance are followed. It also said that devices “should not be used in an attempt to extinguish a PED fire due to the dangers associated with picking up the PED while the device is in an unstable condition (i.e., the fire is still actively burning or the device appears to expanding or popping from heat).” The device should not be moved until thoroughly cooled, FAA said, adding that FAA Fire Safety Branch, ICAO and Flight Safety Foundation guidance materials also stress that a malfunctioning PED should not be handled by personnel.

Once the fire is extinguished, containment devices can be used to secure the PED, FAA said.

Later in December, FAA sent out InFO (information for operators) 17021 making the same basic points.

Notes

- ICAO Dangerous Goods Panel Twenty-Sixth Meeting (DGP/26). “History of the Meeting.” DGP/26-WP (Working Paper)/54. Montreal. Oct. 16–27, 2017.

- Ibid.

- ICAO Dangerous Goods Panel Twenty-Sixth Meeting (DGP/26). “Transport of PEDs by Passengers and Crew.” DGP/26-WP/37. Montreal. Oct. 16–27, 2017.

- ICAO Dangerous Goods Panel Twenty-Sixth Meeting (DGP/26). “Portable Electronic Devices Carried by Passengers and Crew.” DGP/26-WP/43. Montreal. Oct. 16–27, 2017.

Featured image: © ma-rish | iStockphoto

Smart suitcase: © Scharfsinn | VectorStock

Flammable goods warning icon and fire containment icon based on icons by © ahasoft | VectorStock