The operator of a drone that collided last year with a U.S. Army Sikorsky UH-60M Black Hawk had “only a general cursory awareness of regulations and good operating practices,” including a requirement to fly the drone where he could see it, the U.S. National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) says.

In its final report on the Sept. 21, 2017, midair collision near New York’s Hoffman Island, the NTSB cited as the probable cause the drone operator’s “failure … to see and avoid the helicopter due to his intentional flight beyond visual line of sight.” A contributing factor was the operator’s “incomplete knowledge of the regulations and safe operating practices.”

No one was injured in the collision, which occurred in visual meteorological conditions at 1920 local time, two minutes before the end of civil twilight and the official start of darkness. The Black Hawk received minor damage, including a dent on a rotor blade, and the drone, a Dà-Jiang Innovations (DJI) Phantom 4, was destroyed. Some parts of the drone were found lodged in the helicopter.

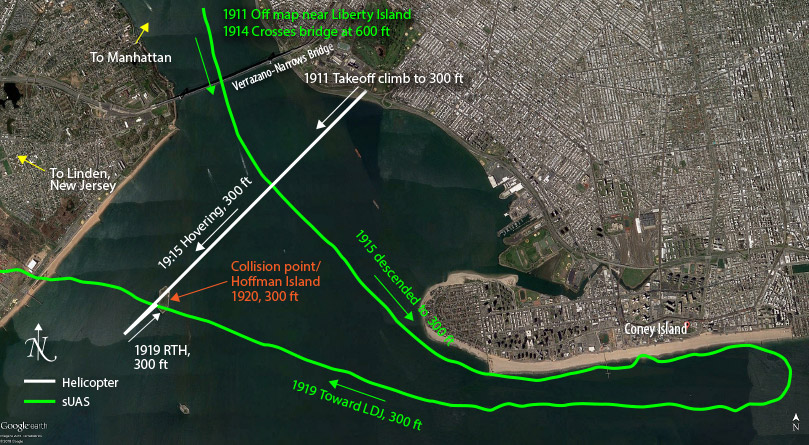

The Black Hawk had been the lead helicopter in a flight of two on an orientation flight in temporarily restricted airspace in the area. The NTSB report said that air traffic control (ATC) radar and recorded data from the Black Hawk showed that the helicopter was flying at 274 ft above mean sea level and had just passed Hoffman Island when it “made contact with what appeared to be a sUAS” — a small unmanned aircraft system, as drones also are called.

The co-pilot, the pilot flying, said that he saw the drone seconds before the impact and immediately reduced the collective but was unable to avoid the collision. The pilot-in-command then took the controls, and the flight continued to the base at Linden, New Jersey, where it landed uneventfully.

Using manufacturer’s records associated with a piece of the drone’s wreckage that was recovered after the collision, NTSB investigators were able to identify and locate the operator, who said he had been unaware that a collision had occurred until investigators told him so.

Using manufacturer’s records associated with a piece of the drone’s wreckage that was recovered after the collision, NTSB investigators were able to identify and locate the operator, who said he had been unaware that a collision had occurred until investigators told him so.

The drone operator told investigators that on the evening of the incident, he had planned to fly the Phantom 4 over the Atlantic Ocean. He launched it from the Brooklyn side of Lower New York Bay, near the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge, which connects the New York City boroughs of Brooklyn and Staten Island. It had been in flight, at about 300 ft, for five minutes before the operator lost the signal.

“The pilot … intentionally flew the aircraft 2.5 miles [4.0 km] away, well beyond visual line of sight, and was just referencing the map on his tablet,” the report said. “Therefore, he was not aware that the helicopter was in close proximity to the sUAS.”

At about 1919, he pressed the return-to-home button on the control tablet and noted that the drone had turned to track northeast to return to its takeoff point, called its home point. Seconds later, a battery-endurance warning indicated that the aircraft had only enough power to return directly to the home point. The data logs ended at 1920, and the last position and altitude recorded matched the position and altitude shown in the helicopter’s recorded data and on ATC radar.

The drone operator said that he lost the signal from the aircraft but “assumed it would return home as programmed,” the incident report said. “After waiting about 30 minutes, he assumed it had experienced a malfunction and crashed in the water.”

Two TFRs in Effect

The collision occurred in uncontrolled Class G airspace, which underlies a portion of New York’s Class B airspace, surrounding some of the busiest airports in the country. At the time of the accident, a temporary flight restriction (TFR) was in effect because of ongoing meetings of the U.N. General Assembly; the TFR prohibited flights of model aircraft and drones within lateral limits of the Class B airspace, from the surface up to 17,999 ft.

A second TFR also was in place, barring the operation of model aircraft and drones from the surface to 17,999 ft within 30 nm (56 km) of Bedminster, New Jersey, because of President Donald Trump’s presence in the area. The drone’s launch point was 30.35 nm (56.21 km) from the center of the TFR, and Hoffman Island was 29.22 nm (54.12 km) from the center.

‘A Lot’ of Experience

The helicopter’s pilot-in-command had 1,570 flight hours in the Black Hawk, and the co-pilot had 184 hours. They said they had no previous in-flight encounters with a drone, and no outside knowledge of them, the report said.

The drone operator told investigators that he had been flying drones recreationally for about two years. He said he had “a lot” of experience with drones; his flight logs listed at least 50 hours of flying time, including 38 flights in the 30 days before the collision, the report said. He said he had no experience with conventional radio-controlled aircraft and did not have a remote pilot-in-command certificate issued by the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA).

“He had taken no specific sUAS training other than the tutorials that are included in the DJI GO4 operating application (app),” the report said. “At the time of the collision, there were no training or certification requirements for hobbyist or modeler pilots.”

The drone operator told investigators that he had heard of the FAA’s B4UFLY app, which tells drone operators — especially those who fly for recreation —which areas they should avoid because of restricted airspace and other conflicts.

He said that he had flown his drones in the area numerous times, including at night, although the aircraft had no additional lighting other than its four position lights.

“When asked about specific regulations or guidance for sUAS flights, he stated that he knew to stay away from airports and was aware there was Class B airspace nearby,” the report said. “He said that he relied on ‘the app’ to tell him if it was OK to fly. He stated he knew that the aircraft should be operated below 400 ft. When asked about TFRs, he said he did not know about them; he would rely on the app, and it did not give any warnings on the evening of the collision. …

“When asked, he did not indicate that he was aware of the significance of flying beyond line of sight, and again stated that he relied on the app display. He said he did not see or hear the flight of helicopters involved in the collision but said that helicopters fly in the area all the time.”

Nevertheless, despite his awareness of the ban on flight above 400 ft, flight logs showed that, during an earlier flight on the day of the incident, his drone had reached 547 ft and had traveled 1.8 mi (2.9 km) from the launch point — a distance “unlikely to be within visual line of sight,” the report said.

“Even though the sUAS pilot indicated that he knew there were frequently helicopters in the area, he still elected to fly his sUAS beyond visual line of sight, demonstrating his lack of understanding of the potential hazard of collision with other aircraft,” the report added.

He also expressed surprise that a helicopter would be flying as low as 300 ft, the report said.

The report noted that the Phantom 4 — a quadcopter about 13 in (33 cm) in diameter — has a maximum takeoff weight of 3 lb (1.4 kg), a maximum endurance of 28 minutes and a remote controller with a maximum range of 3.1 mi (5.0 km). It also is equipped with a global positioning system (GPS) and a flight controller that enables a number of automated functions.

“Aircraft telemetry and video is transmitted to the remote controller … and displayed on a smartphone or tablet of the pilot’s choice using an app supplied by the manufacturer or various third-part app developers,” the report said. “The pilot used a Samsung tablet with Wi-Fi but no cellular data capability. He did not use any third-party apps to control the aircraft.”

The Phantom 4 also is equipped with geospatial environment online (GEO) to help pilots avoid specific types of airspace, including TFRs, by sending warnings to the smartphone or tablet being used by the operator.

The report quotes DJI as saying that GEO “provides pilots with up-to-date guidance on areas where flight may be limited by regulation or raise safety concerns. In addition to airport location information, flyers will have real-time access to live information on temporary flight restrictions (and) locations such as prisons, nuclear power plants and other sensitive areas where flying may raise non-aviation security concerns. The GEO system is advisory only. Each user is responsible for checking official sources and determining what laws or regulations might apply to his or her flight.”

Because the drone operator’s tablet lacked a cellular data connection, the GEO system information about the two TFRs in the area did not download.

“In order for the system to have warned the pilot, he would have had to connect to the internet at some point while the TFR was active,” the report said. At the time, however, the DJI GEO’s TFR function had been temporarily shut down by DJI because of a problem with the system; there was no notice to users about the shutdown, the report said.

This article is based on NTSB Aviation Incident Final Report DCA17IA202AB and associated documents.

Featured image: © DKart | iStockphoto

Broken drone photo and map: U.S. National Transportation Safety Board