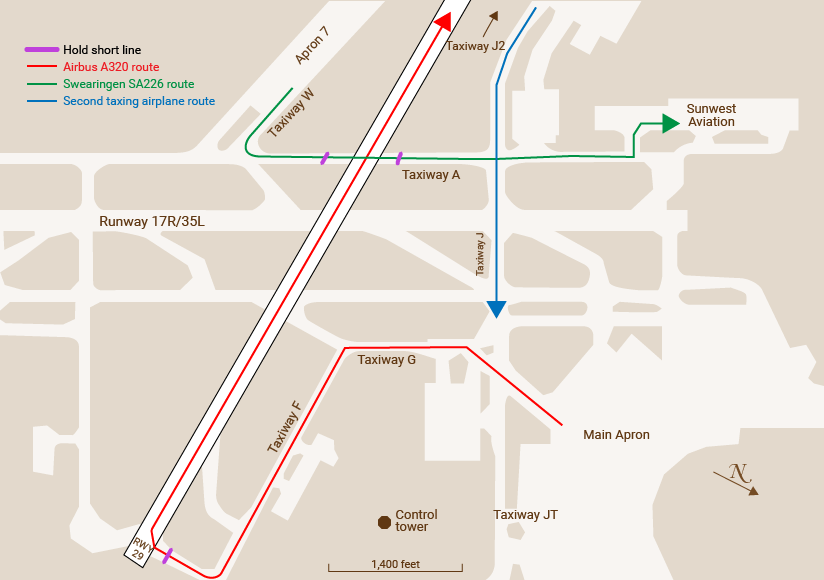

An Air Canada Airbus A320-200 was accelerating through 100 kt for takeoff from Calgary International Airport’s Runway 29 when the pilots saw a smaller airplane cross in front of them on an intersecting taxiway. The A320’s crew continued the takeoff, crossing the intersection — airborne — 14 seconds after the smaller aircraft had taxied across the runway centerline.

The Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) says the air traffic control (ATC) practice of allowing aircraft and ground vehicles to cross seldom-used runways without prior coordination among controllers contributed to the Dec. 2, 2016, runway incursion, which was classified as a Class B “serious” incursion.1

The TSB said the incursion, which occurred at 1649 local time, “as twilight was approaching darkness,” was preceded by a change in wind direction, a corresponding change in the active runways and the merger of several controller positions.

According to the TSB’s timeline, at 1648:39, as the A320 was taxiing to Runway 29, the combined tower controller issued a takeoff clearance.

At 1649:12, the combined ground controller told the crew of a Sunwest Aviation Swearingen SA226-TC that they were cleared to cross Runway 29 on Taxiway A. At 1649:19, the same controller verified that the SA226’s intended path would not conflict with that of another taxiing airplane.

At 1649:34, the SA226, still on Taxiway A, crossed the southern hold-short line for Runway 29. At1649:36, the SA226 crossed the Runway 29 centerline, and at 1649:46, it crossed the northern hold-short line.

Three seconds later, at 1650:00, the A320, already airborne on Runway 29, crossed Taxiway A at 136 kt.

The A320 crew said later that, because the SA226 was more than halfway across the runway when they first saw it, they chose to continue their takeoff. Each crew had been unable to see the other’s airplane because of twilight lighting conditions, the relative positions of the two aircraft and the fact that their navigation lights blended with surrounding lighting, the report said.

The ground controller who had been “simultaneously overseeing the movement of two other aircraft, inadvertently applied the usual practice of clearing aircraft to cross Runway 29 without coordinating with the tower controller,” the TSB report said, describing the controller’s action as “a strong habit intrusion error.”2

The report noted that the Nav Canada Manual of Air Traffic Services (MATS) instructs controllers not to authorize aircraft or ground vehicles to operate on an active runway “unless you have coordinated with the tower controller.” Similar instructions appear in the Calgary Control Tower Operations Manual, which calls for ground controllers to “coordinate access to runways that are not his/her jurisdiction with tower controller(s).”

Less Frequent Operations

Calgary International Airport has four runways, including Runway 17L/35R, which was completed in June 2014. Since its construction, operations on Runway 29 have become “considerably less frequent,” the report said.

“Given the significantly increased capacity offered by the parallel runways [17/L/35R and 17R/35L], Runway 29 is used only during periods of strong west winds and for noise abatement purposes at night, but is most frequently used during night operations. The control tower is usually ‘single stand’ at that time, meaning that one controller has possession of all runways and coordination is not required.”

As a result, the report added, “there was little opportunity to maintain proficiency in Runway 29 operations during the day, and no training to practice those operations, including the need to coordinate before crossing Runway 29. Additionally, the runway jurisdiction system on the controllers’ displays, a tool to remind them of which controller is responsible for which runways, did not provide a sufficiently compelling cue to ensure coordination with tower control before clearing an aircraft to cross Runway 29.”

On the day of the incursion, the controller in the combined ground position was in charge of non-nighttime operations on Runway 29 for only the third time since parallel runway operations began in 2014, the report said.

Other Incursions

This was the fifth runway incursion involving Runway 29 since parallel runway operations began, the report said, noting that Nav Canada’s safety management system (SMS) had identified “issues of declining proficiency with Runway 29 operations.” Although some recommended corrective actions were implemented before this incursion, other recommended safety measures were not put in place, the report said.

The report said that after the third incursion, Nav Canada indicated that there were ongoing discussions about including Runway 11/29 simulation in annual refresher training, and that the Calgary Tower Operations Committee was “looking into technical and procedural cues that could be implemented to support Runway 11/29 operations,” the report said. The actions that were reportedly under consideration were not implemented.

After the fourth incursion in March 2016, a Nav Canada operational safety investigation found that computer display system’s runway jurisdiction system (RJS) — a memory aid designed to remind controllers which of them had control of Runway 29 — was ineffective and recommended action to identify other risk controls to serve the same purpose, including making sure that the RJS display was not blocked by pop-up dialog boxes.

That recommendation was implemented before the December incursion, and several others were said to be under consideration but were not implemented, the report said.

“The local corrective action taken, together with the length of time between occurrences, led to a conclusion that the risks associated with these types of occurrences were as low as reasonably practicable,” the report added. “As a result, further safety action that had been identified as being under consideration was not pursued.

“Further, the identified safety actions that were under consideration … were not formally tracked or followed up in Nav Canada’s SMS. If proposed safety actions are not tracked to completion, there is an increased likelihood that identified safety risks will not be effectively mitigated.”

14 Hazards

Between April and June 2014, before parallel runway operations began, Nav Canada conducted 10 hazard identification and risk assessment activities that identified 14 hazards related to the upcoming change. None related specifically to the reduction in use of Runway 29 or to its use in taxiing, the report said.

The report singled out three of the identified hazards that the TSB considered relevant to this particular runway incursion:

- “The increased number of runway crossings that would be required due to the configuration of the airspace (such that aircraft hangered on the west side of the airport, departing eastward, would need to cross Runway 17R/35L).” Actions suggested to address this hazard included the monitoring of operations during the early days of parallel runway operations as well as controller training and establishing a minimum staffing level.

- “Limited opportunity to use a crossing runway configuration.” Before opening the parallel runways, the airport had frequently allowed takeoffs and landings on intersecting runways in an effort to increase capacity. It was expected that controllers would lose their proficiency in intersecting runway operations; attempts to mitigate this risk included limiting hours of noise abatement configurations in order to avoid the use of crossing runways, increasing spacing between aircraft when crossing-runway operations were in use, and using different runways for arrivals and departures.

- “Non-routine operations.” The risk-assessment activities determined that in the early days of parallel runway operations, controllers might encounter a configuration that had not been included in their training. The assessment suggested actions to mitigate the hazard, including “tactical coordination of new configurations, an increase in coordination meetings between stakeholders and additional staffing during the early days of the operation.”

When the mitigations were in place, the report said, “the level of risk associated with each of the hazards identified was deemed low.”

TSB Watchlist

| Year | Total Runway Incursions | Serious Runway Incursions |

|---|---|---|

|

Source: Transportation Safety Board of Canada |

||

| 2011 | 386 | 10 |

| 2012 | 355 | 3 |

| 2013 | 422 | 5 |

| 2014 | 462 | 3 |

| 2015 | 416 | 6 |

| 2016 | 411 | 21 |

The report noted that the TSB Watchlist, which identified key issues in transportation safety, has included “risk of collisions on runways” since 2010. In the report on the incursion, the TSB noted that it is especially concerned about events defined as serious runway incursions. The report cited data from 2011 through 2015, which showed there were 2,041 runway incursions at Canadian airports, including 27 serious incursions (Table 1).

“The Board remains concerned that serious runway incursions will continue to occur until better defences are put in place,” the report said, citing its report on 2007 event at Toronto/Lester B. Pearson International Airport that said, “until flight crews in aircraft that are taking off or landing receive direct warnings of incursions onto the runway they are using, the risk of high-speed collisions will remain.”3

The current report noted that although automated systems have been tested in the United States, a recent increase in serious incursions at U.S. airports has led the U.S. National Transportation Safety Board to begin an investigation of causes and effects of incursions.

“Industry and the regulator are taking helpful steps to share data and other information to improve local airport procedures, but few technological defences to alert flight crews and vehicle operators of runway conflicts have been considered or implemented in Canada,” the report said. “More leadership is required from Transport Canada, Nav Canada, airport authorities and industry to ensure they are making full use of technologies to maintain runway safety.”

After this incursion, Nav Canada implemented a number of changes intended to limit vehicle movements near Runway 11/29 and to remind controllers when Runway 11/29 is in use.

This article is based on TSB Aviation Investigation Report A16W0170, “Runway Incursion: Nav Canada, Calgary Control Tower, Calgary International Airport, Alberta; 02 December 2016.”

Notes

-

- According to International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) definitions, there are two categories of serious incursions:

- Class A incursions, in which a collision is narrowly avoided; and,

- Class B incursions, in which there is a significant potential for collision.

- The report defines <span style=”font-style: normal;”>habit intrusion</span> as “a frequently occurring form of attentional slip in which an intended sequence of actions is replaced by a stronger, well-rehearsed schema. The result of this type of error is that a typical or normal sequence of actions is carried out in place of the desired sequence.”

- TSB. Aviation Investigation Report A07O0305, “R&M Aviation Inc., Learjet 35A, N70AX; Toronto/Lester B. Pearson International Airport, Ontario; 15 November 2007.”

- According to International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) definitions, there are two categories of serious incursions:

Featured image: © Veni | iStockphoto

Diagram: Susan Reed; source: Transportation Safety Board of Canada