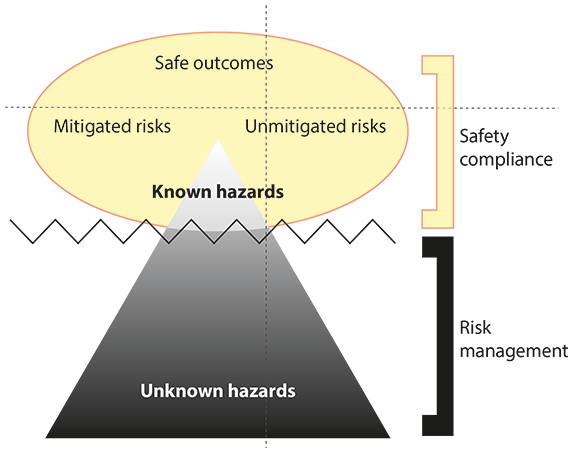

The U.S. Federal Aviation Administration’s (FAA’s) new compliance philosophy1 has introduced an oversight approach that proactively manages risks through the “identification and control of existing or emerging safety issues” and by concentrating resources on mitigating risk and problem solving. Traditionally, safety professionals focused on controlling known hazards while also trying to anticipate if or when unknown hazards would surface (Figure 1). For example, a special issue of Risk & Regulation in 2010 devoted eight articles2 to a discussion of risk management related to close calls, near misses and early warnings. The articles represented different industries and issues, ranging from oil refinery accidents to failures in physicians’ clinical performance to vulnerabilities in nuclear reactors.

To complicate matters, many definitions of risk exist, depending on whether the word is used in everyday conversation or by experts in different domains. In an effort to standardize the definition, the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) defined risk simply as “the effect of uncertainty on objectives.”3 However, uncertainty may exist because of either potential events or their consequences, and whether information is ambiguous or missing. Further, uncertainty can either positively or negatively impact one’s objective.

Today, an organization’s capability to accumulate information about risk and to use that information to develop mitigations can be labeled risk intelligence (or risk intel), that is, generating previously unknown knowledge or understanding from data. However, gathering risk intelligence is dependent on correctly positioning and providing resources to people, processes, systems and tools, including processes for transforming data into useful information for risk analysis, mitigation and planning purposes. The ability of an organization to gather risk intelligence increases the quality and quantity of information available for improved decision making.4,5

In the pursuit of safe outcomes, many aviation safety professionals have produced vast amounts of risk intelligence about the characteristics of known hazards. As illustrated by Figure 1, however, we need better methods to develop risk intelligence about unknown hazards. We cannot directly understand something we do not know, so are there new ways to capture characteristic signals or markers that can point out an underlying issue? This use of such indicators is very common in the medical field, where a full blood test, for example, provides an analytically valuable dashboard of chemical markers.

Figure 1 — Safety Compliance vs. Risk Management

Source: Barry C. Davis, Julia Pounds, Paul Krois and Melissa Wishy

Our operational definition of risk is an effort to clarify the relationship between safety and risk so that both can be measured. The intent is for aviation safety professionals to be able to better recognize how and when the risk occurs, what influences it, etc.

Given that a common goal of the global aviation community is to continually increase the level of safety, we offer a very simple solution for the complex problem of identifying risk:

- We define risk as unintended variation; and,

- We believe that today’s high level of safety can be increased by reducing unintended variation.

Aviation relies on a system of systems highly dependent on procedures to maintain flight safety and efficiency. Rules and regulations for all airspace users specify procedures containing best practices for executing safe operations. Like drivers of cars approaching head-on must know to stay on their own side of the road, safe aviation operations depend on the shared expectation that applicable procedures and best practices will be followed.

Maintaining safety requires controlling risk. However, safety is usually defined relative to absence of risk, a concept with no single agreed-upon definition. Instead, controlling risk often has involved various combinations of expectation, intent, opacity, action and outcome regarding either an entity’s purposeful engagement with an unknown or the outcome of an entity’s having encountered an unknown. This inconsistency poses problems for aviation professionals who are charged with identifying and reducing risk to improve safety levels. We suggest a common definition so that safety professionals can objectively identify, measure, study and reduce risk; identify changes in risk; and determine the effectiveness of risk mitigation strategies.

We defined risk as unintended variation because some intended variation among users of the National Airspace System must be tolerated to permit them to flexibly respond in unanticipated or uncontrollable circumstances. For example, some variation is tolerated and expected when users are allowed to exercise discretion and judgment to safely accomplish their goals. These situations are generally covered in safety controls within policies in phrases such as “the operator may discontinue the alerts if …” and “the documentation should include … .” Unintended variation means that which is outside approved and predetermined safe tolerance levels and is therefore not intended to occur.

In sum, alertness for unintended variation to identify risk provides an objective method for managers of aviation organizations in government and industry to address risk. Measuring the presence or absence of unintended variation is an objective approach to the more imprecise concepts of risk.

The scientific concept of variation is not new. To apply risk intelligence to aviation, however, involves understanding the nature of variation, whether variation is present and where none is intended. Our definition also aims to help safety professionals to take advantage of statistical methods For example, statistical process-improvement techniques have long been used to identify and remove the causes of variability in manufacturing. Processes have characteristic attributes that can be measured, analyzed, controlled and improved. Any variation during the process or in its outcomes can be identified and corrected by effective quality assurance and quality control programs. Stable and predictable results are attained by reducing variation in processes.

This insight into processes extends across many domains of human activity, including aviation safety, as illustrated by the examples below. It also can lead us to a better understanding about how, when and where unintended variation goes unnoticed in processes and systems. To appreciate the pervasive nature of the problem, we need only to begin asking questions like the following.

Do we want unintended variation in machine parts that are used in safety-critical equipment?

Do we want unintended variation in information that is used in critical safety decisions?

Is risk introduced if there is unintended variation in how we:

- Process information through systems;

- Format information to be used by systems;

- Identify hazards;

- Describe a hazard’s characteristics;

- Describe hazards for developing mitigations;

- Evaluate hazards for prioritizing resources;

- Implement mitigations in systems;

- Distribute mitigations in systems;

- Make decisions;

- Implement security; and,

- Manufacture aircraft parts?

While this is not a complete list, unintended variation clearly is a marker that signals risk whether it involves a safety-related decision, mechanism, aircraft part or other element within the aviation system.

Barry C. Davis manages FAA’s Air Traffic Safety Oversight (AOV) Information Standards. Paul Krois is involved with FAA human factors research. Julia Pounds, Ph.D., manages AOV’s Research and Analysis. Melissa Wishy is a subject matter expert and senior policy analyst with AOV Information Standards.

This article represents the opinions of the authors and does not reflect FAA policy.

Notes

- FAA. “National Policy: Federal Aviation Administration Compliance Philosophy.” Order 8000.373. June 26, 2015.

- ESRC Center for Analysis of Risk and Regulation. Special issue on close calls, near misses and early warnings. London, U.K.: London School of Economics and Political Science, July 2010.

- ISO. ISO 31000/ISOGuide 73. Risk Management — Vocabulary, 2009.

- Apgar, D. Risk Intelligence: Learning to Manage What We Don’t Know. Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2006.

- Funston, F. Surviving and Thriving in Uncertainty: Creating the Risk Intelligent Enterprise. Hoboken, New Jersey, U.S. John Wiley and Sons, 2010.

Featured image: © Tifonimages | Adobe Stock; © stevanovicigor | istockphoto.com