About 18 percent of flight crews on business aviation flights from 2013 through 2015 failed to conduct a complete pre-takeoff check of flight controls, according to a National Business Aviation Association (NBAA) study.1

The study — urged by the U.S. National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) in a safety recommendation prompted by its investigation of the fatal May 31, 2014, crash of a Gulfstream G-IV in Bedford, Massachusetts, U.S., which followed the pilots’ failure to remove the airplane’s gust lock before takeoff2 — analyzed 143,756 business aviation flights conducted in 379 business aircraft during the three-year period.3

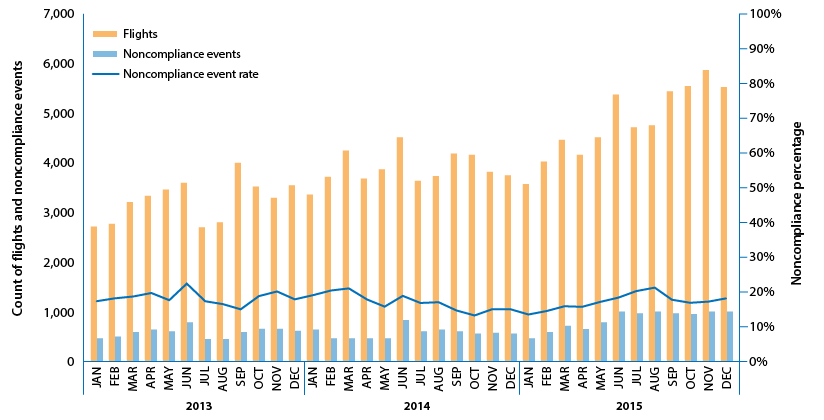

Results of the NBAA study showed that about 15 percent of those flights “began with a partial flight control check, and 2 percent began without a full, valid check,” the NBAA said. The organization defined a “full, valid” check as “the stop-to-stop deflection of all flight controls specified by a manufacturer’s aircraft flight manual.” A month-by-month breakdown is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 — Flight Control Checks Before Takeoff, 2013–2015

Source: National Business Aviation Association

The NBAA’s report on the study, released in late September, described the overall noncompliance rate of 17.66 percent as “very disturbing” and said that, “despite the post-accident reduction in the rate of warning events, there is still a significant challenge concerning noncompliance with manufacturer-required routine flight control checks before takeoff.

“It is troubling to find that nearly 18 percent of every 100 business aircraft flights included in the data were not in compliance with manufacturer-required routine flight control checks before takeoff and that two of those 100 flights conducted no flight control check before takeoff at all.”

‘Habitual Noncompliance’

In the G-IV accident that prompted the NTSB recommendation, four passengers, two pilots and a flight attendant were killed during a rejected takeoff in night visual meteorological conditions from Bedford’s Hanscom Field for a flight to Atlantic City, New Jersey; the airplane was destroyed after rolling through the overrun area and across grass, and then colliding with approach lights, a localizer antenna and perimeter fencing (ASW, 12/15–1/16, p. 51).

The NTSB cited as the probable cause “the flight crewmembers’ failure to perform the flight control check before takeoff, their attempt to take off with the gust lock system engaged and their delayed execution of a rejected takeoff after they became aware that the controls were locked.”4

Contributing factors were the flight crew’s “habitual noncompliance with checklists, Gulfstream Aerospace Corporation’s failure to ensure that the G-IV gust lock/throttle lever interlock system would prevent an attempted takeoff with the gust lock engaged and the Federal Aviation Administration’s failure to detect this inadequacy during the G-IV’s certification.”

The NTSB’s post-accident review of data from the airplane’s quick access recorder (QAR) showed that the pilots had not conducted complete flight control checks before 98 percent of their previous 175 takeoffs, “indicating that this oversight was habitual and not an anomaly,” the NTSB report said.

“The flight crewmembers’ total lack of discussion of checklists during the accident flight and the routine omission of complete flight control checks before 98 percent of their last 175 flights indicate that the flight crew did not routinely use the normal checklists or the optimal challenge-verification-response format [in conducting their checklists],” the report said. “This lack of adherence to industry best practices involving the execution of normal checklists and other deficiencies in crew resource management eliminated the opportunity for the flight crewmembers to recognize that the gust lock handle was in the ‘ON’ position and delayed their detection of this error.”

The report said the crew’s “pattern of noncompliance” with the flight control check was “troubling” and apparently intentional. Because they generally flew together and had not recently flown with other pilots, accident investigators could not talk with colleagues who could discuss their reasons for noncompliance. There was, therefore, little evidence on which to analyze their actions.

“However,” the report added, “the crewmembers’ behavior can be placed in context and some possible reasons for it can be identified by referring to the broader scientific literature on procedural noncompliance.”

The report added that the NTSB found no existing data enabling it to determine the extent of procedural noncompliance in business aviation. That lack prompted the agency’s safety recommendation to the NBAA, calling on the organization to “work with existing business aviation flight operational quality assurance groups … to analyze existing data for noncompliance with manufacturer-required routine flight control checks before takeoff and provide the results of this analysis to your members.”

The NTSB report cited previous research that showed that pilots’ disregard of checklists was not uncommon, including a 1990 study by the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration in which two of six airline crews being observed by researchers “neglected to perform all flight phase checklists during a flight.”

The report also cited a report on a study by The LOSA Collaborative that found that line operations safety audit (LOSA) data from more than 20,000 airline flights between 1996 and 2013 showed that 49 percent involved at least one intentional noncompliance error.

A number of theories have been suggested to explain why pilots might disregard required procedures, the NTSB report said, citing “personality characteristics, culture (professional, company and crew), goal conflicts and resource constraints.”

The report added that the “remarkable consistency of this flight crew’s omission of such checks (as indicated by QAR data) suggests shared crew attitudes about the necessity of the flight control check. Although it is unknown whether the crewmembers consciously omitted the performance of a flight control check during the accident flight, it is likely that they decided to skip the check at some point in the past and that doing so had become accepted practice.”

Earlier research found that, when flight crews routinely perform a particular check without noticing any indication that it enhances safety, they may believe that the check is not important and consequently may stop performing the check and [redirect] their efforts toward other actions that they consider more important, the report said.

“Such changes can lead to the development of new group norms about what is expected and an increasing mismatch between written guidance and actual operating practice,” the report added. “This increasing mismatch has been described as ‘procedural drift.’”

Procedural drift probably affected the crew of the accident airplane and their noncompliance with the control check, the report said.

‘Soft’ Defenses

The NTSB was unable to find data on the rate of business aviation flight crew compliance with required flight control checks, even though “checklists, callouts and other SOPs [standard operating procedures] are considered an important ‘soft’ defense against threats and errors in business aviation,” the report said, adding that if the actual rate of compliance is considerably lower than thought, action will be needed to improve checklist usage.

“Fortunately, data monitoring technology now exists to evaluate this question empirically,” the report said, pointing to the Corporate Flight Operational Quality Assurance (C-FOQA) Centerline program, developed in 2005 by Austin Digital, in cooperation with Flight Safety Foundation.

“Data collected through the C-FOQA Centerline program could be analyzed through automated queries to determine the frequency that required flight control checks are accomplished and calculate the rate of omission,” the report said. “Such an analysis would allow the business aviation industry to estimate the magnitude of procedural noncompliance regarding a well-defined before-takeoff safety check.”

The NTSB’s safety recommendation suggested that the NBAA work with the C-FOQA Centerline Steering Committee and other business aviation FOQA groups to analyze data for noncompliance with routine pre-takeoff flight control checks and share the results with NBAA members.

Project Team

In response to the recommendation, the NBAA formed a project team, whose members included C-FOQA groups and other industry safety personnel, to collect and analyze relevant C-FOQA data.

The data showed several classifications of pre-takeoff flight control checks:

- Normal events were those in which “a valid flight-control check was conducted on all control surfaces required to be checked.”

- Caution events were those in which “at least one but not all, of the required control surfaces did not have a valid flight control check on that surface.”

- Warning events were those in which there was “no valid flight control check of any of the control surfaces that were required to be checked.”

Caution events and warning events both were considered “noncompliant” flight control checks. The noncompliance rate, which averaged 17.66 percent for the three-year period, ranged from a low of 13.35 percent in October 2014 to a high of 21.99 percent in June 2013. The report said the noncompliance data fluctuated from month to month and that the accident report had a “minimal effect … on crew actions in regard to compliance with the manufacturer-required routine normal flight control checks before takeoff.”

During the month before the NTSB’s release of its September 2015 final report on the G-IV accident, the data showed a “noticeable drop in caution events,” but that drop was followed by an increase, the NBAA report said, adding that, overall, the difference in caution event rates before and after the accident was not significant.

“The average warning event percentage prior to the accident was 2.80 percent,” the report said. “After the accident on May 31, 2014, and the release of the preliminary report on June 13, 2014, the average warning event rate was reduced to 1.147 percent, a drop of 50 percent. That may indicate there was a positive reaction to the preliminary report finding that the Bedford crew did not perform any flight control check before takeoff.”

The report concluded that data showed “a consistent trend of incomplete or neglected manufacturer-required flight control checks before takeoff.”

NBAA President and CEO Ed Bolen added, “As perplexing as it is that a highly experienced crew could attempt a takeoff with the gust lock engaged, the data also [reveal] similar challenges across a variety of aircraft and operators. This report should further raise awareness within the business aviation community that complacency and lack of procedural discipline have no place in our profession.”

The NBAA report contained several recommendations, including a call for operators to implement SOPs reflecting manufacturer-required pre-takeoff flight control checks, to establish a flight data monitoring program and to participate in data sharing of information acquired through that program.

Other recommendations called for business aircraft manufacturers to provide operators with “clear requirements and procedures” for pre-takeoff flight control checks; for training centers to emphasize the importance of, and special procedures for, those control checks; and for flight crews to conduct the checks in accordance with manufacturer requirements.

The report also said the NBAA should establish a council of experts in data collection and data sharing to aid the business aviation community in implementing related safety programs.

Notes

- NBAA. NBAA Report: Business Aviation Compliance With Manufacturer-Required Flight-Control Checks Before Takeoff.

- The gust lock system is designed to prevent damage from wind gusts by holding an airplane’s elevator, ailerons and rudder in place while the airplane is parked.

- NTSB. Accident Report NTSB/AAR-1503, Runway Overrun During Rejected Takeoff; Gulfstream Aerospace Corporation G-IV, N121JM; Bedford, Massachusetts; May 31, 2014. Sept. 9, 2016.

- The NTSB accident report said that during the takeoff, the engine pressure ratio failed to reach the expected level because the advancing throttles contacted the gust lock/throttle lever interlock. The pilots continued the takeoff, but when the pilot-in-command attempted to rotate the airplane, “he discovered that he could not move the control yoke and began calling out “(steer) lock is on.” If the crew had rejected the takeoff within 11 seconds after that comment, they could have stopped the airplane on pavement, the NTSB report said. They delayed “until the accident was unavoidable,” the report said.

Featured image: © choja | iStockphoto