More than half of European commercial pilots say their colleagues “are often tired at work” and that pilot fatigue is not taken seriously by their employers, according to a large-scale survey conducted by European aeronautical researchers to evaluate pilot perceptions of safety.1

The report — released in November 2016 by Future Sky Safety, a research program begun by the association of European Research Establishments in Aeronautics — also said that most of the 7,239 pilots who completed the electronic survey believed that the safety cultures at their companies were strong.

Nevertheless, the survey found a divide that separated pilots working for network carrier airlines (flag or legacy airlines) from those working for low-cost and cargo airlines, who had more negative perceptions.

The 7,239 pilots who submitted valid survey responses accounted for about 14 percent of commercial pilots in Europe, and the report said that the respondents were statistically representative of Europe’s pilot population. Ninety-six percent of respondents were male, 62 percent were between ages 31 and 50, 44 percent had more than 10,000 flight hours, and 48 percent had worked for their company for at least 11 years. Fifty-six percent were captains, 43 percent were first officers, and 1 percent were second officers.

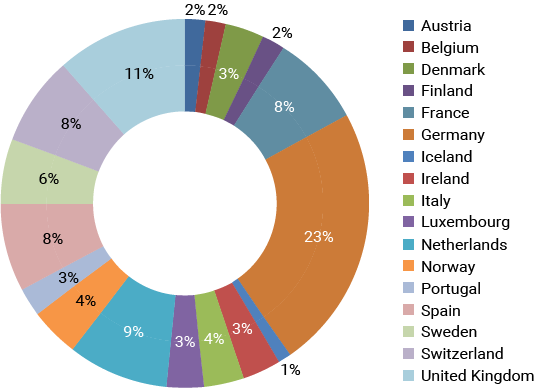

Fifty-five percent worked for a network carrier, and 24 percent worked for a low-cost airline. Others were employed, in smaller numbers, in other segments of the industry (Figure 1). About 88 percent worked on typical contracts, in permanent positions; 11 percent held atypical contracts, which the report defined as being self-employed, working on zero-hours contracts (only when needed by employers), fixed-term (temporary) contracts or pay-to-fly contracts (typically for pilots who pay to accumulate flight time). More participating pilots were based in Germany (23 percent) than in any other country, although participants were based across the continent (Figure 2); in all, about 60 percent of respondents were from five countries — France, Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden and the United Kingdom.

In their answers to a series of questions, survey participants “tended to respond … in a positive fashion,” the report said. “However, there is clear room for improvement, with some groups of pilots showing negative perceptions of safety culture (e.g., those on atypical contracts) and some survey items/dimensions were responded to in a consistently negative fashion (e.g., fatigue).”

The quality of an organization’s safety culture has become a key element in assessing its safety practices, the report said, noting that safety culture is “the cornerstone of an effective safety management system.” Nevertheless, the report added, “there is currently no systematic method or practice of measuring and comparing safety culture amongst pilots.”

Therefore, the report’s authors said, the study was designed to evaluate pilot perceptions of safety culture, using survey responses to compare trends and variations in the safety cultures that exist at different organizations.

More than 90 percent of the pilots who completed the electronic survey said their colleagues were committed to safety, but less than 20 percent said they believed that their employers cared about their well-being, the report said.

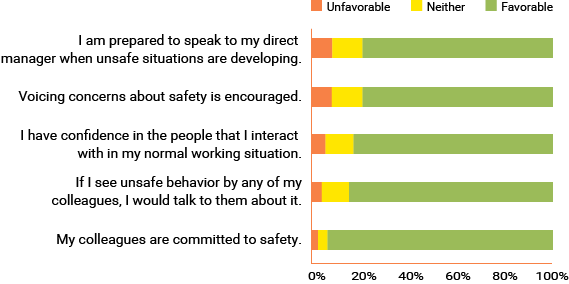

In the section of the survey dealing with pilot perceptions of safety culture within their organizations, the most favorable response was to an item that said “my colleagues are committed to safety”; 94 percent agreed (Figure 3). The report’s authors also noted that 79 percent said they were “prepared to speak to my direct manager when unsafe situations are developing” and that “voicing concerns about safety is encouraged.”

Figure 3 — Most Favorable Responses to Organizational Safety Culture Questions

Source: Future Sky Safety

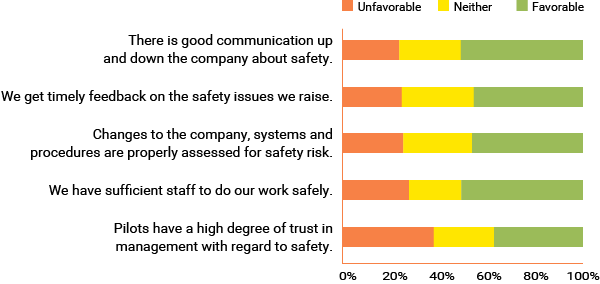

The report said the least favorable answers in the same section were in response to the item “pilots have a high degree of trust in management with regard to safety,” which generated a 38 percent unfavorable response (Figure 4).

Figure 4 — Least Favorable Responses to Organizational Safety Culture Questions

Source: Future Sky Safety

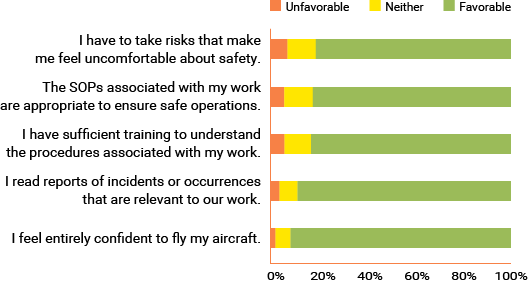

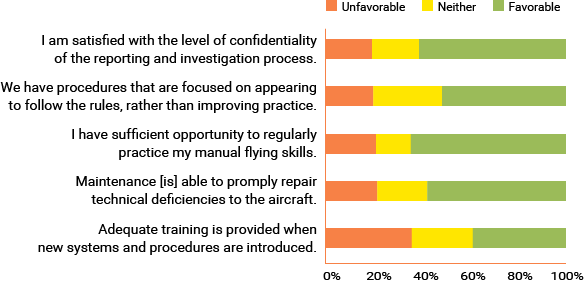

In the section focusing on safety culture as it relates to “the more operational aspects of being a pilot,” the item that generated the most favorable response (91 percent) was “I feel entirely confident to fly my aircraft” (Figure 5). The least favorable response (38 percent unfavorable) was to an item about the adequacy of training: “Adequate training is provided when new systems and procedures are introduced” (Figure 6).

Figure 5 — Most Favorable Responses to Operational Safety Culture Questions

SOPs = standard operating procedures

Source: Future Sky Safety

Figure 6 — Least Favorable Responses to Operational Safety Culture Questions

Source: Future Sky Safety

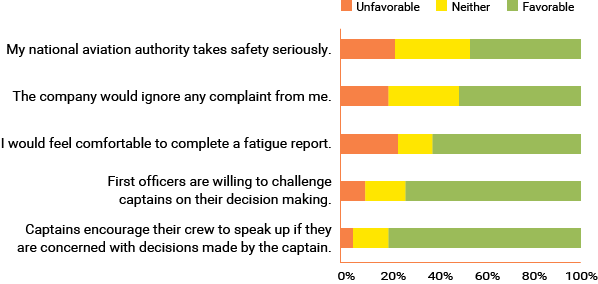

In the section that examined “the working life of pilots … and how much they feel supported by their organisation,” the most favorable response (80 percent) was to an item that said “captains encourage their crew to speak up if they are concerned with decisions made by the captain.” The report’s authors also singled out another item in which “only 46 percent agreed that their national aviation authority takes safety seriously” (Figure 7).

‘Often Tired’

The least favorable response (58 percent unfavorable) in this section was to the item that said “pilots in this company are often tired at work.”

In response to other fatigue-related items, 51 percent said that fatigue was not taken seriously by their airline, 32 percent said they would feel “fully supported by my company” if they reported they were unfit to fly (because of fatigue), and 24 percent said they would “feel comfortable to complete a fatigue report.”

The report noted “a high degree of variation” in responses to the fatigue questions, with significantly poorer scores for low-cost and cargo operators than all other company types, including not only network and charter/leisure operations but also general aviation, aerial work/ambulance/surveillance and helicopter business/VIP/state flights. The report also noted “significantly higher” scores for aerial work/ambulance/surveillance operations than for charter and network flights.

Overall, although the responses to some survey items were similar for employees of many different companies, the responses to other items were “divergent and heterogeneous,” the report said. For example, on a scale of 1 to 5 (with 1 as the most negative response and 5 as the most positive), 94 percent of companies had mean scores higher than 3.5 in response to the item “colleague commitment to safety”; the range was between 3.39 and 4.48.

Conversely, the range was 1.88 to 3.80 in response to “perceived organisational support”; 40 percent of company mean scores were less than 2.5.

‘Mostly Positive’

The report said responses to survey questions showed that the pilots’ perceptions of their safety culture were “favourable,” with responses to 59 percent of the items receiving mean scores above 3.5, “indicating mostly positive perceptions.” Responses to 41 percent of items averaged less than 3.5 — an indication of “mixed or negative perceptions,” the report said.

However, the report added, pilots with managerial roles in operations, training or safety had “a significantly more positive perception than those who do not hold any management role across a number of safety culture dimensions. This may be because these pilots are potentially in a position of power to make changes to improve safety; therefore, there may be self-desirability bias here.”

The report also suggested that pilots in managerial positions might not observe as many operational problems, either “because they are hidden from them, or it may reflect communication issues (i.e., pilots in management positions are more aware of the reasons behind changes to SOPs [standard operating procedures] and, therefore, understand them better.)”

The document added, “In terms of safety culture dimensions, pilots tend to have concerns over the issues of fatigue management; management commitment to safety, staff and equipment; and perceived organisational support.”

Specifically, pilots’ concerns were focused on “trust in management with regard to safety, receiving feedback on safety issues, training, national aviation authorities and pilots being tired at work,” the report said.

When researchers examined the mean scores of companies with at least 30 survey respondents, they found that company scores on some items were similar, but on others, they varied considerably. “This indicates that safety practices at aviation companies differ, leading to differential beliefs on issues such as the extent to which management is committed to safety or resourcing,” the report said.

An additional comparison examined mean scores by pilot nationality (for nationalities represented by more than 100 survey respondents) and found only slight differences, the report said.

Overall results showed that most believed that their colleagues shared a commitment to safety, that they were encouraged to voice safety concerns and that they “do not need to take risks that make them feel uncomfortable about safety.”

Respondents were especially concerned about two areas:

- Worker fatigue — “the workforce feeling tired and … how fatigue is managed by the company.”

- Organizational support — a “relative newcomer to safety culture,” which research shows is associated with safety practices. “The implication is that where a workforce feels unsupported and unsatisfied with their organization, they feel the organization is not committed to safety, does not recognise the pressures they face and does not value their contributions to safety.” This concern was frequently cited by pilots working on atypical contacts, the report said.

One of the report’s authors, Anam Parand, a researcher at the London School of Economics and Political Science, said the survey’s results present “a learning opportunity for airlines to enable the industry to build on its reputation for safety and to work with pilots and regulators to ensure that it continues to remain a safe mode of transport.”

Next Steps

The report recommended that the industry address the concerns raised by the survey, including the pilots’ belief that their fatigue concerns are not taken seriously by their employers.

“This needs to be addressed by actions undertaken jointly with regulators, airlines and representative bodies, to educate managers and pilots about the potential safety implications and also the necessity to improve this cultural dimension,” the report said.

Other recommendations called for workshops to allow pilots, managers and decision makers to discuss the results of the survey and what actions might enhance safety culture, and for regulatory authorities to take into account the differing perceptions of safety culture when working toward continued safety.

In addition, the industry should “begin systematically measuring and exploring safety culture in commercial aviation companies,” the report said, adding that additional research is needed into the variations in safety culture within different companies. Such research already is under way at several airlines, and the company-specific focus allows for input from company managers and employees other than pilots, the report said.

“If this is achieved,” the report said, “learning on safety culture (e.g., sharing best practices amongst organisations) can begin to occur across European airlines as it already occurs for air traffic organisations.”

Regional Airlines Survey

In a separate, unrelated survey on safety issues at European regional airlines, responses from 15 safety managers and 35 CEOs and accountable managers showed that members of the CEO group consistently were more confident than safety managers about their organization’s ability to manage risk.2

The survey — administered to European Regions Airline Association aviation professionals by Baines Simmons in August and September 2016 — found that the CEO group averaged 79 percent confidence in questions involving the “four pillars” of a safety management system: safety policies and objectives, safety risk management, safety assurance and safety promotion. The safety manager group, however, averaged 61 percent confidence.

In their answers to a specific question — “how often are commercial decisions that involve operations made following a process of operational risk assessment using measured facts?” — the CEO group’s score was 80 percent, compared with 44 percent for safety managers.

The report noted the “considerable disparity of opinion” in the responses and comments, which ranged from “close to always” to “safety is completely ignored.”

The report explained the variations of opinion, saying, “Safety managers, with their oblique and specialist view of an organisation’s safety performance, often have a greater insight into the ‘lived reality’ of risk management in an organization but struggle to convincingly articulate this.”

The report noted a need to resolve the disparity between views of the CEO group and the safety managers, adding that change would require “a move away from the [CEO’s] perception-based view of how well an organization is managing safety to an evidence-based approach.” Regulators will increasingly expect such evidence “as the industry moves towards performance-based oversight,” the report said.

Notes

- Reader, T.W.; Parand, A.; Kirwan, B. European Pilots’ Perceptions of Safety Culture in European Aviation. November 2016.

- Baines Simmons. European Regions Airlines Safety Performance Survey. October 2016.

Featured image: Composite and pilot icons: Susan Reed; background: © -strizh- | iStockphoto