Although numerous eye injuries have been caused by exposure to laser beams, a small study by a U.S. Air Force physician found that pilots who were exposed “at altitude, outside of critical phases of flight,” were unlikely to suffer serious lasting harm to their eyes.1

Laser beams “pose a hazard to the eye and numerous injuries have been documented,” said the report on the study, conducted by Kevin C. Dietrich and published in the November issue of Aerospace Medicine and Human Performance, the journal of the Aerospace Medical Association (AsMA). “However, there lies a misunderstanding in the propensity to damage aircrews’ eyes during an exposure.”

The report characterized the possibility of laser beam exposure during cruise flight as a “distraction and not a threat.”

The document added, “Laser exposure is more apt to disrupt flight and not directly injure aircrew vision while flying at altitude.”

The report noted that intermediate- and high-power lasers have caused injuries, especially to the eyes and skin. The study searched electronic medical records from July 2016 through January 2017 at an unnamed medical clinic and identified 21 reported exposures to laser beams. All patients were members of military aircrews, including pilots, boom operators and loadmasters, and none was using protective lenses at the time of the exposure. All exposures were to beams from ground-to-air lasers, and because all occurred during refueling or normal operations, the study presumed that they all occurred above 10,000 ft above ground level.

Of the 21 crewmembers, none was diagnosed with an acute eye injury.

The report acknowledged the limitations associated with the small number of patients involved in the study, the subjective reporting of their experience and the non-standardization of lasers pointed at the various aircraft.

“However, no encounters yielded any evidence of acute injury, which is to be expected, given the flight level and the limitations of lasers,” the report said, noting that, beyond a certain distance from a laser, an eye injury is no longer possible.

When the crewmembers sought medical attention after the events, they were “reflexively sent to optometry” and given eye drops that dilated their pupils to enable examinations of their eyes, the report said. “This naturally led to a gounding period where aircrew were not permitted to perform flying duties.”

During periods of military deployment, the report added, “this may reasonably lead to an under-reporting of exposures because of fear of ‘grounding’ and adverse mission impact.”

The report said that crewmembers should be given more information to help them recognize symptoms of flash blindness and glare — two common results of laser beam exposure2 — and recover from the symptoms.

The presence of either of these symptoms does not indicate damage to the retina, the eye’s light-sensitive innermost lining, said the report, which cited earlier research that concluded that, in cases involving commercial handheld lasers, the human blink reflex protects against retinal damage.

The study included a review of case reports of non-crewmembers who, while on the ground, suffered damage to their eyes and a loss of vision because of their exposure to laser beams, noting that a common trait of the exposures was the close proximity of the laser.

In aviation-related cases, the report noted that the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) recorded 17,764 incidents between 2010 and 2014 in which laser beams struck aircraft. “Of those exposed, zero injuries were reported,” the report said. In earlier studies of 64 laser strikes involving commercial airline pilots, there were no definite findings of damage to the eyes, the report said.

Decline in Laser Strikes

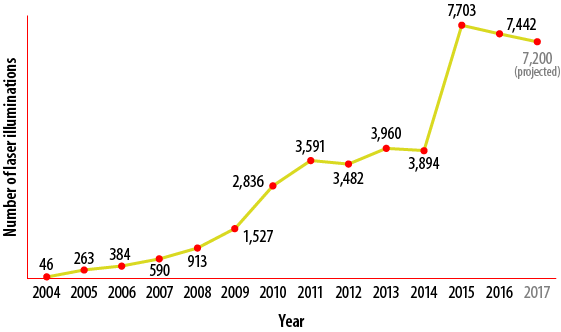

FAA data show that, in the first six months of 2017, some 2,933 laser strikes were reported to the FAA, 15 percent fewer than the 3,441 strikes reported in the comparable period in 2016 but 9 percent more than the 2,692 reported in the first half of 2015. An independent group advocating safer use of laser pointers, LaserPointerSafety.com, forecasts — based on its analysis of data reported since 2007 — that the number of strikes for all of 2017 will total 7,200, down from 7,442 reported in 2016 and 7,703 in 2015.3

Figure 1 — Laser Illuminations Reported to FAA, 2004–2017*

Source: U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and LaserPointerSafety.com

Although lasting eye injuries to crewmembers are unlikely, the FAA and other specialists say that a pilot’s inability to see past the laser light and the temporary flash-blindness present a serious threat to aviation safety.

In an aeromedical safety brochure, “Laser Hazards in Navigable Airspace,”4 the FAA cautioned that “aviators are particularly vulnerable to laser illuminations when conducting low-level flight operations at night. The irresponsible or malicious use of laser devices can threaten the lives of flight crews and passengers.”

The FAA says that no accidents have been attributed to laser strikes on aircraft, “but given the sizeable number of reports and debilitating effects that can accompany such events, the potential does exist.

“Sudden exposure to laser radiation during a critical phase of flight, such as on approach to landing or departure, can distract or disorient a pilot and cause temporary visual impairment. Permanent ocular damage is unlikely since the majority of incidents are brief and the eye’s blink response further limits exposure. In addition, considerable distances are often involved, and atmospheric attenuation dissipates much of the radiant energy.”

Although laser energy dissipates over distance, a laser beam — which projects as a small dot — expands in diameter as it travels farther from its source. Often, when the beam strikes a cockpit windscreen, it spreads more, sometimes becoming so large that a pilot cannot avoid it, LaserPointerSafety.com said.

“The laser’s light does not suddenly stop in midair,” the website said in a section intended to discourage anyone who might be considering pointing a laser beam into the sky. “It may pass into clearer air, which does not scatter much light back to the viewer. But the light definitely continues on.

“Instead of hundreds of feet, the laser can be a distraction at a distance of many miles. This is yet another reason why you should never aim a laser at or near an aircraft: If you can see the aircraft or its lights, then [the pilots] can certainly see your laser, and be visually distracted or flash-blinded by it.”

Blocking Laser Beams

Several products are being developed to protect against vision damage associated with laser strikes. Airbus and Metamaterial Technologies Inc. (MTI) announced earlier this year that they were exploring the use of an optical filter designed to block and deflect laser light. MTI says its metaAIR filter, which can be applied to protective eyewear or windshields, can be used night and day and allows users to see their surroundings, including flight deck displays, “as they would naturally.”5

Other products include anti-laser eyeglasses, which block specific colors of light. LaserPointerSafety.com said, however, that unless the glasses are specifically designed for use in aviation, they could limit pilots’ night vision and their ability to see some colors on display screens.

Anticipate and Aviate

In guidelines developed through research and interviews with pilots who have experienced laser strikes to their aircraft, the FAA recommends that pilots anticipate a laser strike “when operating in a known or suspected laser environment” and that the pilot monitoring should be prepared to take the controls, if necessary.

The next steps on the FAA’s list are to “aviate — check aircraft configuration and (if available) consider engaging the autopilot to maintain the established flight path; navigate — use the fuselage of the aircraft to block the laser beam by climbing or turning away; and communicate — inform air traffic control of the situation.”

Turning up cockpit lights will minimize the effects of further illuminations, which often occur because of movement of the laser as well as the airplane, the FAA says.

After exposure to a laser beam, pilots should “not exacerbate” their injuries by rubbing their eyes, the FAA says, adding that if visual symptoms continue after landing, the pilot should visit an eye doctor.

Notes

- Dietrich, Kevin C. “Aircrew and Handheld Laser Exposure.” Aerospace Medicine and Human Performance Volume 88 (November 2017): 1040–1042.

- Flash blindness is defined by the FAA as an “inability to see … caused by bright light entering the eye and persisting after the illumination has ceased.” The FAA defines glare as a “temporary disruption in vision caused by the presence of a bright light … within an individual’s field of vision. Glare lasts only as long as the bright light is actually present within the individual’s field of vision.”

- The FAA also identifies other common visual effects of laser beam exposure not discussed in the report: after-image, in which an image remains in the visual field after exposure to a bright light; and blind spot, a loss of vision in part of the visual field.

- LaserPointerSafety. “Concerned About Laser Pointers? Want Them Used Safely?”

- FAA. “Laser Hazards in Navigable Airspace.”

- MTI. “Laser Protection.”

Featured image: composite, Susan Reed; eye, © eclipse_images | iStockphoto; and laser, © GoodLifeStudio | iStockphoto

Pilot: U.S. Federal Aviation Administration