The pilot of an Airbus AS350 was halfway through the sixth of seven planned round trips between Skagway, Alaska, U.S., and a remote dog camp on the Denver Glacier when he told the camp manager that deteriorating weather might halt the flights.

“But don’t give up on me yet,” the pilot added in a statement that the U.S. National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) described as “consistent with self-induced pressure to complete the day’s series of flights” on May 6, 2016.

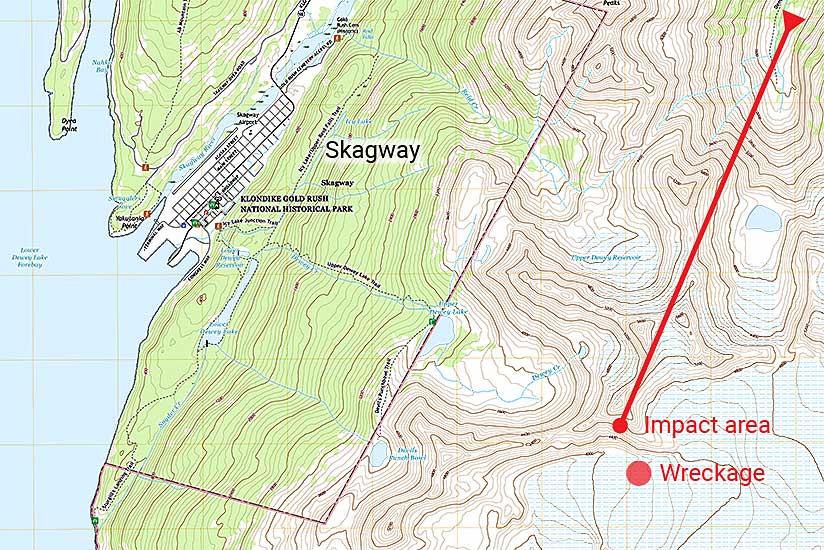

The pilot then took off to complete the sixth round trip, likely flying under visual flight rules into an area of instrument meteorological conditions (IMC), losing visual references and, at about 1900 local time, crashing the AS350 into a snow-covered mountain 4 mi (6 km) southeast of Skagway. The crash killed the pilot and caused substantial damage to the helicopter, the report said.

The pilot’s decision to continue the flight into IMC — which resulted in his loss of visual reference and in the subsequent controlled flight into terrain — was cited by the NTSB as the probable cause of the accident. Contributing factors were “the pilot’s self-induced pressure to complete the flight and the operator’s failure to maintain operational control over the flight,” the NTSB said in its final report on the accident.

Seven Round Trips

The pilot was prepared at 0800 to begin the day’s scheduled seven continuous round-trip flights — with each round trip taking about 18 minutes — in the helicopter, operated by TEMSCO Helicopters under contract with Alaska Icefield Expeditions, which offered dog sledding tours. Low ceilings delayed his takeoff from the TEMSCO Waterfront Heliport in Skagway. While waiting for more favorable conditions, he attended company orientation training at 0900 and provided helicopter loading training for new employees at 1300. After the training session ended at 1530, he determined that wind conditions were unsuitable for flight but were expected to improve.

At 1630, the operator told the manager of the Alaska Icefield Expeditions dog camp on Denver Glacier that the seven round-trip flights, which were to be conducted without shutting down the engine, were about to begin. At 1645, the pilot departed from Skagway with 10 dogs and one musher; he returned to Skagway to pick up and deliver another 10 dogs and another musher.

“The dog camp manager stated that it was snowing as these flights arrived,” the report said, adding that when the base manager in Skagway, who had operational control of the day’s flights, questioned the pilot about weather conditions, the pilot replied “that there was turbulence around the toe of the glacier and that he was keeping his airspeed down for a smoother ride.” The pilot’s report prompted the base manager to cancel a scheduled external load flight.

At 1747, the helicopter left Skagway on the third trip, again carrying one musher and 10 dogs. He reported “a little bit of in-flight icing” at 3,000 ft, the report said.

“The base manager asked the pilot what kind of precipitation he was experiencing, and the pilot reported ‘wet snow.’ The base manager told the pilot ‘to do what he thought was best.’ The pilot responded that he would evaluate the icing conditions as he flew on the subsequent flights.”

The accident report, however, noted that the base manager had operational control, and that, because both the TEMESCO operations manual and the AS350 B2 flight manual prohibited flight in icing conditions, “the pilot’s statement should have prompted the base manager to suspend the flights.” His failure to do so, the report said, “may have been due to the difference in experience between the base manager, who had been operating these flights for eight years, and the pilot, who had been operating these flights for 25 years.”

The report described the fourth and fifth round trips as uneventful. Each flight left the Skagway base carrying one musher; the fourth flight carried 10 dogs and the fifth flight, 11 dogs.

At 1840, the helicopter left Skagway to begin the sixth round trip, carrying one musher and 12 dogs. They flew through Paradise Valley, which the musher described as “wide open,” with a rainbow in the sky. However, the musher added that clouds were moving in as the helicopter approached the glacier.

“The passenger reported that the clouds were ‘thick,’ and that he could not see up the glacier toward the dog camp,” the report said. “The passenger further reported that the western mountain wall near the glacier was visible at the time, so the pilot elected to follow the wall into the dog camp ‘very slowly.’”

The passenger said the helicopter was “very low” over a bluff and closer to the mountain wall than on any of his earlier flights to the dog camp. At the time, the dog camp manager said that winds had increased to 20 to 30 mph just before the sixth flight arrived and that it was snowing. By then, clouds obscured the bluff and visibility toward Paradise Valley was about ¼ mi (403 m).

“Before the pilot left, he signaled for the dog camp manager and told him that he was ‘not coming back in this weather,’” the report said. “The dog camp manager verbally agreed. The dog camp manager told the pilot to be safe, and the pilot said … ‘but don’t give up on me yet.’”

At 1852, the helicopter left the dog camp for the return flight to Skagway.

The dog camp manager watched the helicopter travel about 1/8 mi (201 m) toward Paradise Valley before turning around and then heading north. He estimated visibility to the north as about ¼ mi, and said that snow was falling considerably harder and that winds remained between 20 and 30 mph.

Tracking data showed that the helicopter “was making multiple 360-degree turns before turning to the north and east and continuing to make turns,” the report said, adding that the aircraft’s altitude was “trending up” before a descent near the accident site.

Around 1900, the Skagway base manager asked about the helicopter’s status. He observed the flight tracking computer’s indication that the helicopter was northwest of the dog camp about 2,000 ft above ground level, but his radio calls were unanswered. The company’s emergency response plan was activated, and the base manager flew with an observer toward the last known coordinates of the accident helicopter.

The initial search was hindered by low ceilings and blowing snow, but at 2009, the base manager and the observer saw the wreckage of the AS350 near a frozen glacial lake about 2 mi (3 km) northeast of the dog camp. The helicopter was unable to land at the accident scene, and dog camp workers on snow machines also were unable to reach the site because of winds ranging from 50 to 70 mph, visibility between zero and “a few hundred feet,” steep terrain and the possibility of avalanches. A Coast Guard helicopter reached the site later that night, and an aviation survival technician confirmed that the pilot had been killed.

Veteran Pilot

The 66-year-old commercial helicopter pilot had 7,190 flight hours, including about 5,700 hours in the make and model of the accident helicopter. He also had private pilot privileges for single-engine land airplanes. He did not have a helicopter instrument rating, and one was not required. At the time of the accident, he was in his 25th season with TEMSCO Helicopters, founded in 1958 to conduct a range of helicopter operations.

The company’s Skagway base manager, 30, had accumulated about 3,445 flight hours and held a commercial pilot certificate for helicopters and an instrument helicopter rating. He had worked for TEMSCO in Skagway for eight years.

The helicopter was manufactured in 1991 as an AS350 B; it was converted in 1992 to an AS350 BA and in 2003 to an AS350 B2. It had 10,191 hours, and its Safran (formerly Turbomeca) Arriel 1D1 turboshaft engine had 4,282 hours. The most recent inspection of the airframe and engine was completed Dec. 17, 2015; maintenance records showed no indication of any uncorrected mechanical discrepancies.

The helicopter did not have a radar altimeter, and at the time of the accident, one was not required, the report said. The helicopter also was without a flight data recorder and cockpit voice recorder; neither was required.

The helicopter cabin had been configured by TEMSCO with a rear-seat assembly that was folded against the cabin wall and two wooden boxes for transporting dogs. The boxes were stacked behind the front seats and were secured in front by two cargo straps attached to four seat belt attachment points in front of the aft cabin wall; the straps were secured to rear seat belt attachment points in front of the wall, traveled over the boxes and were secured at the front seat passenger seat belt attachment points. Between the lower box and the cabin floor were a tarp, a blanket and some wooden shoring.

“With the configuration of the two cargo straps, forward restraint was present,” the report said. “However, no lateral restraint was present. Neither dog box had a placarded weight value on the outside of it.”

An examination of the straps yielded no information about their make or model and no information about the straps’ maximum load rating. The report noted that the straps were stained by an unknown substance and marked by scrapes in various locations.

A placard on the helicopter’s control pedestal said the “distributed loads maximum” for the rear cabin floor was 682 lb (309 kg), said the report, which calculated that the two wooden dog boxes weighed a combined 190.5 lb (86 kg); wooden boards used for positioning on the cabin floor weighed 9.5 lb (4.3 kg); and the straps, a tarp and a blanket weight 5 lb (2.3 kg). The combined weight of 205 lb (93 kg) was not included in the cargo manifest documents or in the helicopter’s weight and balance records.

The cargo manifest form for the first four flights from Skagway to the dog camp listed the total weight of the 10 dogs as 500 lb (227 kg). On the fifth flight, with 11 dogs in the helicopter the weight was listed as 550 lb (249 kg). On the sixth flight, the dog weight was expected to be 600 lb (272 kg) for 12 dog passengers.

“For all six flights from Skagway to the dog camp, the weight of the dog boxes and related items (205 lb), combined with the dog weight, resulted in the structural limitation of 682 lb being exceeded,” the report said.

‘Behavioral Traps’

The report noted that the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has repeatedly discussed effective aeronautical decision making, citing FAA-H-8083-21, the Helicopter Flying Handbook, which described “numerous classic behavioral traps that can ensnare the unwary pilot.”

The document noted that pilots, especially experienced pilots typically “try to complete a flight as planned, please passengers and meet schedules. This basic drive to achieve can have an adverse effect on safety.”

This article is based on NTSB accident report ANC16FA023 and supporting documents.

Featured image: © PixieMe | Adobe Stock

Map: Base, U.S. Geological Suvey and data, U.S. National Transportation Safety Board

Accident aircraft: U.S. National Transportation Safety Board