Spurred by recent difficult, time-consuming and costly searches for flight recorders after airplane crashes in remote areas without radar coverage, the U.S. National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) is pressing for alternative methods of locating aircraft wreckage and recovering critical flight data.

In a safety recommendation letter to Michael Huerta, administrator of the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), the NSTB outlined eight recommendations, all aimed at ensuring that accident investigators have timely access to cockpit voice recorder (CVR) and flight data recorder (FDR) data.

Those data are “some of the most important information sources available to help determine causes of aviation accidents,” the NTSB said in the letter, dated Jan. 22. “As such, recovering the recorders is an investigative priority at the crash site.”

The NTSB’s action came shortly before the International Civil Aviation Organization’s (ICAO’s) High Level Safety Conference agreed in early February to recommend adoption of a 15-minute aircraft tracking standard, which ICAO Council President Olumuyiwa Benard Aliu described as a first step in building a foundation for global flight tracking. The measure could be formally adopted later this year by the ICAO Council, he said.

Both the NTSB and ICAO cited the March 8, 2014, crash of Malaysia Airlines Flight 370, a Boeing 777 that disappeared with 239 people aboard en route from Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, to Beijing. Months of searching by 82 aircraft and 84 vessels from 26 countries have failed to turn up any sign of the 777, which is presumed to have crashed in the southern Indian Ocean after straying from its planned route. At press time, the safety investigation, and a criminal investigation by the Royal Malaysian Police, were continuing, although the Malaysian government said in late January that both investigations were “limited by the lack of physical evidence … particularly the flight recorders.”

The NTSB also cited the June 1, 2009, crash of Air France Flight 447, an Airbus A330, into the Atlantic Ocean not quite three hours after departure from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, for a flight to Paris (ASW, 8/12). All 228 people aboard were killed. Some wreckage was found within a few days, but the flight recorders were not recovered until April 2, 2011; the two-year search cost about $40 million. Information on the recorders was crucial to the French Bureau d’Enquêtes et d’Analyses (BEA) in reaching its conclusions about the circumstances surrounding the accident.2

In the two years before Flight 447’s recorders were recovered, the BEA convened a 120-member international working group — with members from civil aviation authorities, investigative bodies, aircraft and recorder manufacturers, and satellite service providers — to study flight data transmission, recorder technology and techniques involved in locating aircraft wreckage. The working group’s efforts have provided a foundation for more recent proposals by ICAO, the NTSB and others.

Tracking

According to the NTSB, the working group’s review of the circumstances surrounding 44 accidents involving air transport category aircraft found that, in 95 percent of the accidents, if the aircraft had transmitted their position every minute, the last reported position would have been within 6 nm (11 km) of the impact point.

“In the case of Air France Flight 447, the ACARS [aircraft communications addressing and reporting system] was configured to transmit the aircraft’s position about once every 10 minutes,” the NTSB said. “Given the aircraft’s cruising speed and altitude, this resulted in a search area with a radius of 40 nm [74 km] from its last reported position. Such a large area made the search much more challenging. If the aircraft had reported its position more frequently, the search area could have been significantly reduced.”

Two years after the accident, Air France changed the data link communications systems on its long-haul airplanes to enable position-reporting once a minute in some situations, the NTSB said.

The agency also noted that, in the aftermath of the Air France accident, the European Commission said that it is developing additional regulatory material to improve the tracking of aircraft. ICAO and one of its working groups have held meetings to discuss the tracking of aircraft and the locating of aviation accident scenes, and have proposed requirements for a worldwide system for tracking aircraft not only during abnormal flight conditions but also during routine flights.

“The NTSB supports the international efforts under way in this area and believes similar action should be taken in the United States,” the agency said. “Therefore, the NTSB concludes that aircraft should broadcast sufficient information to facilitate a quicker identification of an accident location, a faster search and rescue response and a more effective underwater search effort.”

Along those lines, one of the NTSB’s recommendations calls on the FAA to require that most transport category aircraft flown in extended overwater operations be equipped with “a tamper-resistant method to broadcast to a ground station sufficient information to establish the location where an aircraft terminates the flight as the result of an accident within 6 nm of the point of impact.” The provision should apply to aircraft operated in U.S. Federal Aviation Regulations Part 121 air carrier or Part 135 commuter and on-demand flights that are required to have cockpit voice recorders and flight data recorders, the NTSB said.

Those affected aircraft also should be equipped with “an airframe low-frequency underwater locating device that will function for at least 90 days,” the NTSB said. The current requirement is for the signal from an underwater locator beacon to last at least 30 days.

Data Recovery

The NTSB said it also is promoting data-recovery methods that do not depend on the immediate retrieval of flight recorders from underwater crash sites.

“Locating and recovering flight recorders in overwater accidents has been more problematic than those occurring on land,” the agency said, adding that on rare occasions, data have been lost because the recorders were exposed to water or fire or because searchers were unable to recover the devices.

As an example, the NTSB cited the July 28, 2011, accident involving Asiana Airlines Flight 991, a Boeing 747 cargo plane that crashed into the sea west of Jeju Island, South Korea, killing both pilots — the only people in the airplane — during a planned flight from Seoul to Shanghai, China. The South Korean Aircraft and Railway Accident Investigation Board (ARAIB) has not issued a final report, but preliminary reports note that the crew had reported a fire to air traffic control and was attempting to divert to Jeju when the accident occurred.3

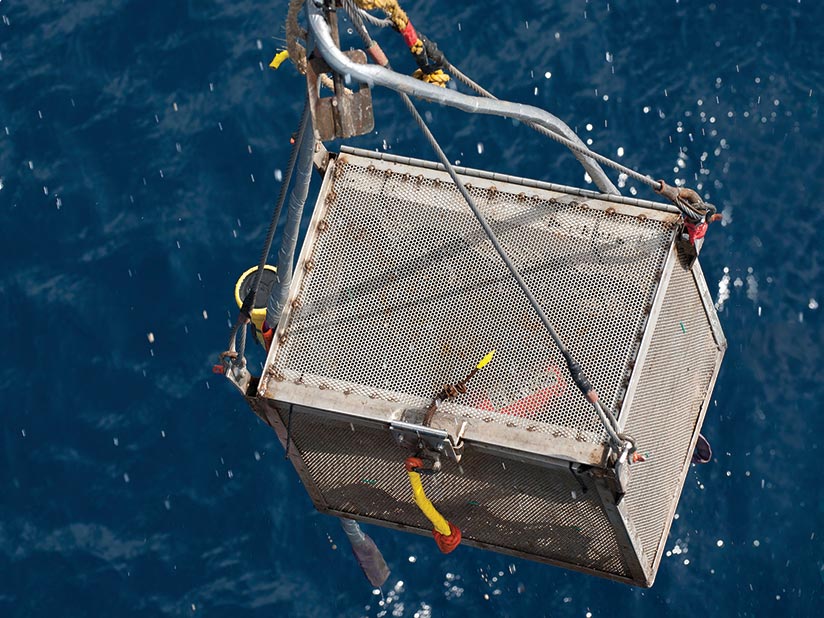

Deployable recorders, which combine traditional CVRs and FDRs and can be ejected from aircraft in case of a crash, might be useful in similar situations, the NTSB said, noting that they have been used successfully for years in military and overwater helicopter operations. They separate from aircraft in case of structural deformation of the fuselage or in case they are submerged in water, and can float indefinitely. They are equipped with emergency locator transmitters to aid searchers.

Triggered Transmission

An alternative to deployable recorders is the triggered transmission of flight data, a technology that involves monitoring selected aircraft parameters; if those parameters on any given flight deviate from normal operating parameters, the deviation triggers the transmission of critical data to satellites — along with, in some cases, a limited amount of data stored before the triggering event.

Triggered flight data transmission already is being used in some aircraft, and improvements are being developed for higher-speed data transmission, the NTSB said.

The agency recommended that the FAA direct operators of newly manufactured Part 121 and Part 135 aircraft that are used in extended overwater operations and required to have a CVR and FDR to also have “a means to recover, at a minimum, mandatory flight data parameters.” Recovery should not require underwater retrieval, the NTSB said.

The safety recommendation letter added that the FAA should work with ICAO, civil aviation authorities worldwide and other aviation safety entities to develop consistent standards for improved aircraft position reporting and methods of data-recovery that do not require underwater retrieval.

The NTSB included among its safety recommendations several provisions that supersede earlier recommendations, calling on the FAA to identify ways to prevent the intentional disabling of flight recorder systems on new and existing air transport category aircraft and to require that crash-protected cockpit image recording systems be installed in all new and existing aircraft that are required to have a CVR and a digital FDR.

Notes

- BEA. Final Report on the Accident on 1st June 2009 to the Airbus A330-203, Registered F-CZCP, Operated by Air France, Flight AF 447, Rio de Janeiro–Paris. July 2012.

- The BEA report traced the accident’s origins to blocked pitot tubes and the resulting unreliable airspeed information, excessive control inputs, and confusion on the flight deck.

- ARAIB. Interim Report No. ARAIB/AAR1105, Crash Into the Sea After an In-Flight Fire; Asiana Airlines, B747-400F/HL7604; 130 Km West of Jeju International Airport; July 28, 2011. Sept. 17, 2012.