A system of anonymous, voluntary reporting of fatigue by pilots and flight attendants can be used to help identify and correct fatigue hazards that might otherwise remain unknown, according to a study of a fatigue reporting system at one airline.1

The study of approximately 309 pilots and 674 flight attendants2 at the short- and medium-haul airline from Sept. 1, 2010, to Aug. 31, 2011, found that the rate of fatigue-report submission among pilots was 103 reports per 1,000 persons; the rate among flight attendants was 68 reports per 1,000 persons. The report on the study — published in the August issue of Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine — did not name the airline, but all three authors were medical or crewing officials with BMI, British Midland International.

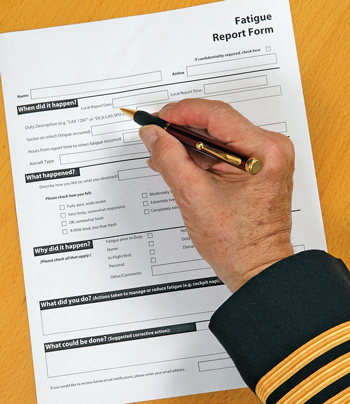

Data for the study were gathered from fatigue report forms (FRFs), which were submitted by pilots and flight attendants to provide information about fatigue-related work events.

“Crews were requested to complete an FRF if they stood themselves down due to fatigue, were unable to attend work due to fatigue, had a general concern about fatigue or a fatigue-related safety event had occurred,” the report said.

During the one-year period, crewmembers submitted 78 FRFs; of that number, 32 reports were submitted by pilots and 46 by flight attendants. Two individuals submitted more than one FRF. The study determined that 81 percent of FRFs submitted by pilots and 93 percent of those from flight attendants described events in which the crewmember was unable to work because of fatigue.

The paper FRFs asked for information about the crewmember’s recent sleep and duty time, the time of day of the event and related “aspects of fatigue-related impairment,” the report said.

The study’s goal was to collect data to help identify fatigue hazards and fatigue mitigation strategies, the report said, adding that self-reporting of fatigue can identify problems that elude fatigue prediction modeling software.

Among the fatigue-related problems discovered through the self-reporting process were the quality of hotel accommodations, commuting distances between the airport and hotel or home, and the “hassle factor” associated with individual airport conditions or technical problems.

For example, the report said, several FRFs that cited “rostered duty pattern” fatigue were submitted by crewmembers on the Tehran, Iran, to London route. The FRFs said that “Tehran-London flight duty … [had] a high ‘hassle factor,’” the report said. “This resulted in a decision by the crewing manager to schedule days off following this particular trip.

“Several reports were received relating to the overnight London-Moscow-London flight, a long duty, which ends within the window of circadian low.3 A metric altimetry operation used within Russian airspace, novel to most flight crew, could increase their workload. A decision was taken to avoid scheduling this duty at the end of a [six-day] block of work.”

Both examples, the report said, involved schedules that complied with regulatory flight time limitations, labor union requirements and the System for Aircrew Fatigue Evaluation (SAFE) software.

Report Analysis

When an FRF was submitted, it was reviewed by the airline’s medical officer. His findings, along with the report, were forwarded to the crewing manager for an independent review. When both agreed that fatigue was the primary cause of the episode described by the crewmember, the FRF was assigned to one of five primary causal categories (see “Fatigue Categories”):

Category 1 — rostered duty patterns;

Category 2 — operational disruption;

Category 3 — layover accommodation;

Category 4 — domestic [issues]; and,

Category 5 — no obvious cause.

Fatigue Categories

The study of crewmembers’ fatigue reports assigned each report to one of the five following primary causal categories:1

- “Category 1: Rostered duty patterns — effect of early starts, trends related to the time of day, effect of multiple sectors, effectiveness of daytime versus overnight sleep, effect of working several consecutive days. The investigator used this category when no other identifiable cause was found and the associated duty had a moderately high, albeit acceptable, [score in an analysis using the System for Aircrew Fatigue Evaluation (SAFE)].

- “Category 2: Operational disruption — flight delays, last-minute roster changes, flight diversions, adverse weather, etc., explicitly stated on the report or discovered after investigation of actual duty worked.

- “Category 3: Layover accommodation — problems with the layover hotel accommodation or transport provided by the company explicitly stated on the report.

- “Category 4: Domestic — domestic in origin, child care, lengthy commute, misread roster, or noisy neighbors explicitly stated on the report. (Actual commute time was recorded by the reporter on the FRF [fatigue report form]. A commute time more than two hours immediately before the start of a duty was considered to be a risk factor if not explicitly stated by the reporter and no other cause was identified.)

- “Category 5: No obvious cause was determined for the fatigue or the report was related to sickness rather than fatigue.”

— LW

Note

- Houston, Stephen; Dawson, Karen; Butler, Sean. “Fatigue Reporting Among Aircrew: Incidence Rate and Primary Causes.” Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine Volume 83 (August 2012): 800–804.

The categories were determined after a review of the results of a small-scale study conducted immediately before the main study, the report said, noting that the aviation industry lacks any standard for categorizing fatigue reports according to cause.

Analysis of the FRFs showed that 27 percent of reports were associated with the rostered duty pattern — more than any other category — and among them were the reports involving the flights from London to Moscow and Tehran. Operational disruption was cited for 24 percent, domestic for 23 percent, and layover accommodation for 17 percent. Nine percent of reports had no obvious cause or were considered “invalid,” in most cases because further investigation determined that the crewmember was ill rather than fatigued.

Fatigue reports that were linked to operational disruption included 10 reports submitted in December 2011 that cited heavy snow in the United Kingdom, the report said. “Many London airports were snow-closed, and crews found themselves delayed or stranded down-route,” the document added.

Of the FRFs with a domestic cause, most were associated with commuting to work, the report said. Most of the study participants drove to work, and information in the narrative section of the FRFs indicated that they experienced difficulty with “extraordinarily heavy traffic because of road closures, accidents or poor weather conditions” and that these problems resulted in longer commutes.

Other domestic causes of fatigue included childcare requirements that interrupted the crewmember’s rest, misreading a duty roster and a noisy neighbor.

The mean monthly report frequency was 6.5, although the number of FRFs filed each month ranged from one in August 2011 to 15 the previous month. The report traced the increase to the airline’s introduction in May of a new hotel for crew layovers; that month, the number of FRFs increased to 11, up from just two that had been submitted in April. Fourteen FRFs were submitted in June and 15 in July.

“There were problems with excessive noise caused mainly by wedding celebrations in the hotel grounds,” the report said. “There were nine reports citing ‘hotel noise’ as the cause for fatigue submitted during [May, June and July]. By the end of July, at the airline’s request, the hotel had installed double-glazing in the crew bedrooms, and no further noise reports were received.”

Just Culture

During the course of the study, crewmembers were reminded of the airline’s confidentiality and voluntary reporting protections, the report said.

“There must be the expectation that the information will be dealt with fairly and in the interests of safety,” the document added. “High reporting rates may indicate an organizational culture committed to identifying and reducing fatigue rather than a truly high [fatigue] rate.”

Notes

- Houston, Stephen; Dawson, Karen; Butler, Sean. “Fatigue Reporting Among Aircrew: Incidence Rate and Primary Causes.” Aviation, Space, and Environemal Medicine Volume 83 (August 2012): 800–804.

- These numbers represented the “midpoint size” of the crew population in February 2011.

- The circadian low is the time of day when an individual experiences the greatest sleepiness, based on his or her body clock.