The pilot of a Genesis Helicopters Bell 206B felt a vibration and a “grinding sensation,” saw the low rotor RPM warning light illuminate and was preparing to ditch when the main rotor stalled and the helicopter plunged into the water and sank in Pearl Harbor, 20 ft from the shore of the Hawaiian island of Oahu.

A rear-seat passenger who had been trapped in his seat drowned, the pilot and two passengers were seriously injured, and the remaining passenger received minor injuries in the Feb. 18, 2016, accident, which the U.S. National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) attributed to “the in-flight failure of the engine-to-transmission drive shaft due to improper maintenance, which resulted in low main rotor rpm and a subsequent hard landing to water.”

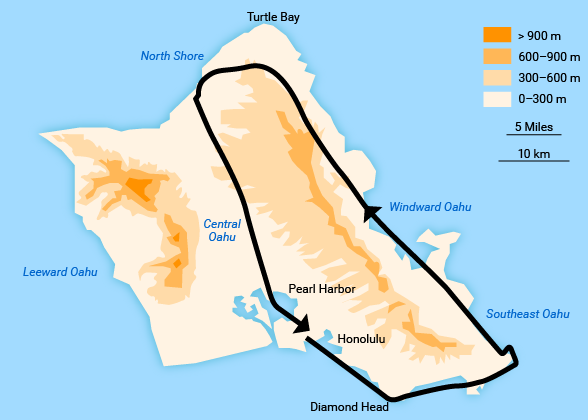

The pilot told accident investigators that on the day of the accident, before what was to be the first tour flight since replacement of the helicopter’s tail rotor drive shaft, he and the company mechanic’s assistant conducted “a pretty good preflight.” Then he boarded his four passengers, whose seat positions had been determined according to weight-and-balance calculations, and conducted a final walk-around inspection before beginning the flight, which left Honolulu International Airport (HNL) about 0935 local time. He flew the helicopter along the eastern and northern shores of Oahu before turning south to fly over the central part of the island toward Pearl Harbor.

As the helicopter approached nearby Ford Island, he felt a vibration throughout the cabin that seemed “different,” the report said. Because of the vibration, the pilot decided to return to HNL. However, the vibration stopped, and he instead turned left to give passengers a view of the USS Arizona Memorial, which honors U.S. sailors and Marines killed in Japan’s surprise World War II attack on Pearl Harbor.

After the turn, the vibration returned, and the pilot told the HNL airport traffic control tower that he was returning to the airport; the controller told him to hold for other helicopter traffic.

“The pilot stated that, at this point, the vibration developed into a grinding sensation,” the report said. “The main rotor rpm warning light illuminated, and engine rpm began to rise.”

When the engine and rotor rpm needles no longer matched on the power turbine gauge, the pilot “lowered the collective, reduced the throttle and realized the engine and main rotor were no longer connected,” the report said.

He decided to land in a grassy area at the Pearl Harbor Visitor Center, but after seeing people near the area, he instead turned to land in the water, “as close to shore as possible, with hopes that people would come out to help,” the report said. “He stated that, when the helicopter was about 20 ft above the water, it felt like the rotor stalled, the helicopter lost life, and it ‘fell out of the sky.’”

It then descended into the water, the report said.

Three of the four passengers exited the helicopter, but the 16-year-old passenger in the middle seat in the back row was trapped. Witnesses said that several people dove into the water to help and that a federal police officer and a Navy diver “took turns going underwater to cut the [seat belt] straps off the passenger.”

The police officer told accident investigators that the passenger’s life vest apparently had become entangled with the seatbelts, and that the entanglement, along with poor underwater visibility, complicated efforts to extract the passenger. Comments from witnesses and a subsequent examination of the life vest indicated that it may have been partially inflated, but investigators could not determine when it might have inflated or how.

After five or six attempts to free the passenger — and after the helicopter had been underwater for about 15 minutes — they pulled him to the surface, and doctors and nurses who had been visiting the memorial administered CPR but were unable to revive the teenager. The report said that a review of medical treatment records showed “evidence consistent with drowning.”

Examination of the seat belts showed that all five had been functioning properly and were not damaged in the ditching, the report said.

900 Flight Hours

The accident pilot estimated that he had about 900 flight hours, including 151 hours in the Bell 206B and 125 hours in the 90 days before the accident; he was unable to locate his logbook, the report said. He had a commercial pilot certificate and a flight instructor certificate with a rotorcraft-helicopter rating and an instrument rating.

The helicopter’s owner, Genesis Helicopters, operated one helicopter under a letter of authorization from the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) to conduct sightseeing flights within 25 mi (40 km) of HNL. The company had four employees — the owner, the accident pilot, a receptionist and the maintenance assistant.

The accident helicopter was manufactured in 1979 and the airframe had recorded 14,212 hours. It was equipped with a 420 shaft horsepower Rolls-Royce Allison 250-C20B turboshaft engine. It did not have an emergency float system.

The report noted that a Bell Helicopter Textron (BHT) representative described the engine-to-transmission drive shaft as an integral part of the power train system (Figure 1).

“The drive shaft (as installed) is comprised of two identical couplings, which are located on either end of the shaft,” the report said. “The internal components consist of two flanges positioned on the ends of the tubular, hollow drive shaft. The assembly requires a retainer ring and packing seal to be positioned against the flange. A drive shaft coupling seal is situated against the packing seal, impeding grease from egressing the coupling assembly.”

The report said that the BHT maintenance manual recommends that, after the drive shaft is disassembled, and before reassembly, its couplings should be hand-packed with grease “over the top of the internal spline teeth to a depth of 0.2–0.3 inch [0.5–0.8 cm].”

A post-accident metallurgical inspection found that the forward coupling “did not appear to be lubricated and that there were multiple indications of exposure to elevated temperature,” the report said. In addition, the external spline teeth on the forward spherical coupling “were worn down to the bottom landings, while comparatively minor wear marks were observed on the mating internal spline teeth of the forward outer coupling.”

The report said that asymmetry in the wear patterns and the indications of heat damage “indicate that the assembly likely failed by overheating due to the lack of lubrication.”

The overheating led to the failure of the spring that centers the spherical coupling; when the spring failed, the spherical coupling’s position shifted and it damaged the outer coupling, which fractured the forward cover plate and wore down the external spline teeth, the report said. Although the engine would have continued operating after the drive shaft’s failure, it would have been unable to drive the main rotor, the report said.

The pilot, the company’s owner and the mechanic’s assistance all told investigators that the engine-to-transmission drive shaft had recently undergone maintenance. However, maintenance logbooks contained no record of the work. The logbooks also held no record of a current annual inspection or a current 100-hour inspection. The most recent entry noted that the tail rotor drive shaft segment was replaced on Feb. 17, 2016.

The company’s owner, who held a mechanic certificate with airframe and power plant ratings in addition to his commercial pilot certificate, told investigators that the accident pilot had observed the engine-to-transmission drive shaft maintenance session and had handed tools to the mechanic’s assistant. The owner said that he also was present for the initial buildup of the shaft, and then left for an hour or more; when he returned to the maintenance area, the mechanic’s assistant had begun installing the shaft in the helicopter.

The owner said that the accident helicopter had been grounded on Jan. 23 because a rubber seal at the base of the short shaft had failed. Parts were ordered on Jan. 25, and the helicopter was being flown again on Jan. 28, the owner said, adding that it accumulated an estimated 31 hours after the repair and before the accident. The owner told investigators that the repair job “must not have gotten put in the logbooks.”

He said that the helicopter was subject to a daily inspection, and that he was “laying eyes on it every night.” When he was asked if he looked at the engine-to-transmission drive shaft, however, he said that he “was supposed to,” and then added, “I think the last time that I laid eyes on the short shaft … [was] probably three or four days before the accident.” He said the helicopter had not been flown for “a span” before Feb. 18 because maintenance personnel were waiting for parts for the tail rotor repair.

Three days after the accident, the owner provided investigators with a component status sheet that indicated that several items “indicated negative time remaining before an inspection was due,” the report said; nevertheless, the owner said that the inspections had been completed but the status sheet had not been updated and that some of the items did not apply because the engine was a “loaner” and the parts in question were not actually in the helicopter at the time.

When the pilot was asked to describe the helicopter’s recent maintenance issues, he said that, among other things, he recalled a 50-hour or 100-hour inspection about a month before the accident during which all bearings were re-greased.

“He recalled one of the hanger bearings on the tail rotor drive shaft had loosened, which was found on the 100-hour inspection,” the report said. “When asked about the engine-to-transmission shaft, he recalled the short shaft seal failing and its subsequent replacement, but he could not recall the date of the replacement.”

The pilot added that in late January, he watched as the owner greased the engine-to-transmission drive shaft “and saw the splines on the gear when the work was being accomplished.”

The mechanic’s assistant, who held neither an airframe nor a powerplant rating, said the short shaft had been removed on Jan. 25 because of leaking grease. The report noted that the assistant said it was removed and cleaned, then inspected by the owner before reassembly, and that the owner “quizzed him on the parts and the type of grease used, and he was present to verify that the proper amount of grease was used before installing the shaft.”

The report concluded that, “It is likely that, when this maintenance was conducted, grease was not applied to the forward coupling as specified in the manufacturer’s maintenance manual. Further review of the maintenance records revealed no entries pertaining to a current annual inspection or 100-hour inspection. Additionally, a component inspection sheet provided by the operator revealed that several required component inspections were overdue and had not been completed at the time of the accident.”

The FAA conducted oversight inspections as required, the report said, but the document added that additional inspections “may have uncovered the inadequate maintenance and documentation, which, in turn, may have prevented the accident.”

This article is based on NTSB aviation accident final report WPR16FA072 and associated documents.

Featured image: © yenwen | iStockphoto

YouTube video: © mrmotofy | YouTube

Map and figure 1: U.S. National Transportation Safety Board