A harness/tether system intended to safeguard occupants of an Airbus Helicopters AS350 B2 during doors-off photo flights was so difficult to quickly unlatch that it was partly to blame for the deaths of all five passengers in a March 11, 2018, crash into New York City’s East River, the U.S. National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) says.

The helicopter lost engine power during cruise flight, and the pilot subsequently conducted an autorotative descent and ditching in the river, the NTSB said in its final report on the accident. The AS350’s emergency flotation system did not deploy, and the helicopter sank into the river, fully inverted, and was submerged 11 seconds after it touched down. In addition to the passengers’ deaths, which were attributed to drowning, the pilot received minor injuries.

U.S. National Transportation Safety Board animated reconstruction of the accident

The NTSB said in the report that the probable cause of the accident was the passenger harness/tether system, “which caught on and activated the floor-mounted engine fuel shutoff lever and resulted in the in-flight loss of engine power and the subsequent ditching.”

The report cited several contributing factors, including “deficient” safety management by Liberty Helicopters, which operated the accident helicopter, and NYONair, which marketed the doors-off photography operations as FlyNYON flights. The companies “did not adequately mitigate foreseeable risks associated with the harness/tether system interfering with the floor-mounted controls and hindering passenger egress,” the report said.

Other contributing factors were Liberty’s actions in allowing NYONair “to influence the operational control” of Liberty’s FlyNYON flights and the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration’s (FAA’s) “inadequate oversight” of revenue passenger–carrying operations conducted under Federal Aviation Regulations (FARs) Part 91 general operating and flight rules.

The report also cited two factors that contributed to the severity of the accident:

- The “rapid capsizing” of the helicopter, a result of the failure of the emergency flotation system to fully inflate; and,

- The use of the harness/tether system, which hindered passengers’ efforts to exit the helicopter.

Planned 30-Minute Flight

The accident occurred during what was planned as a 30-minute aerial photography flight operated by Liberty Helicopters under contract with NYONair, which promoted the passengers’ ability to extend their feet outside the helicopter during parts of the flight. This was possible because the two right doors and the front left door of the helicopter were removed, and the left sliding door was locked in its open position.

To secure the passengers in their seats, each one wore a body harness provided by NYONair that was tethered (using an NYONair tether) to an anchor point inside the helicopter. The passengers also wore FAA-approved seat belts and shoulder harnesses. The pilot wore only the seat belt and shoulder harness.

Visual meteorological conditions prevailed when the sunset flight departed at 1850 local time from Helo Kearny Heliport in Kearny, New Jersey; one passenger was positioned in the left front seat, and four were in rear seats.

“After the flight departed, it traveled past various scenic landmarks,” the report said. “Consistent with the standard operating procedures (SOPs) used for FlyNYON flights, the passengers were allowed (when instructed by the pilot) to position themselves to extend their legs outside the helicopter (Figure 1). The two passengers who had been seated in the rear inboard seats removed their installed, FAA-approved restraints and sat on the cabin floor, wearing their harness/tether systems. The passengers seated in the outboard seats were allowed to rotate outboard in their seats. To enable such freedom of movement, the SOPs allowed the passengers to wear their installed, FAA-approved restraint with the lap belt adjusted loosely and the shoulder harness routed under the arm.”

Figure 1 — Diagram Showing Relative Locations for Helicopter Occupants

Source: U.S. National Transportation Safety Board

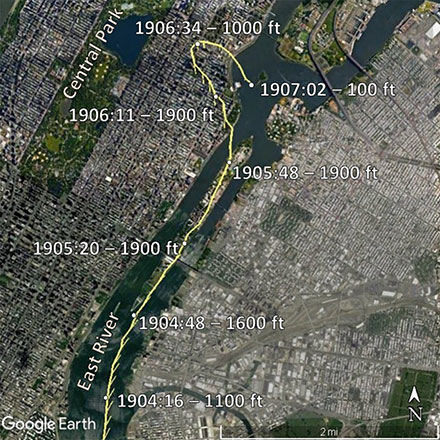

Video and radar data showed that, as the helicopter was flown at 1,900 ft above sea level northwest over Manhattan and toward Central Park, the front seat passenger ─ facing out, with his legs outside the helicopter ─ leaned back as he took photos with his cell phone.

“The on-board video showed that, each time he leaned back, the tail of the tether attached to the back of his harness hung down loosely near the helicopter’s floor-mounted controls,” the report said. “At one point, when he pulled himself up to adjust his seating position, the tail of his tether remained taut but appeared to pop upward. Two seconds later, the helicopter’s engine sounds decreased, and the helicopter began to descend.”

As the pilot prepared to conduct an autorotation, he saw that the fuel shutoff lever was in the shutoff position and realized that it “had been inadvertently moved to that position by the tail of the front passenger’s tether,” which had caught on the lever.

The pilot tried to return the lever to its correct position and to restart the engine, but “the helicopter was too low to allow engine power to be restored in time to prevent the emergency landing,” the report said.

The pilot told accident investigators that he considered landing in Central Park but saw “too many people” on the ground and turned instead toward the East River to ditch the helicopter.

The NTSB concluded that he had conducted a successful autorotation and pulled the activation handle to deploy the helicopter’s emergency flotation system, but the floats did not fully inflate. The report said that the manufacturer had not provided information to enable operators to “recognize the presence of unacceptably high pull forces when activating the system” and that the “high pull forces on the accident helicopter’s activation system (which resulted from an installation anomaly) contributed to the pilot’s mistaken belief that he had taken the necessary action to fully inflate the floats. In addition, a crossover hose failed to perform its intended function of adjusting the asymmetric inflation of the float, the report said.

The helicopter rolled right, then inverted and was submerged 11 seconds after its touchdown around 1908.

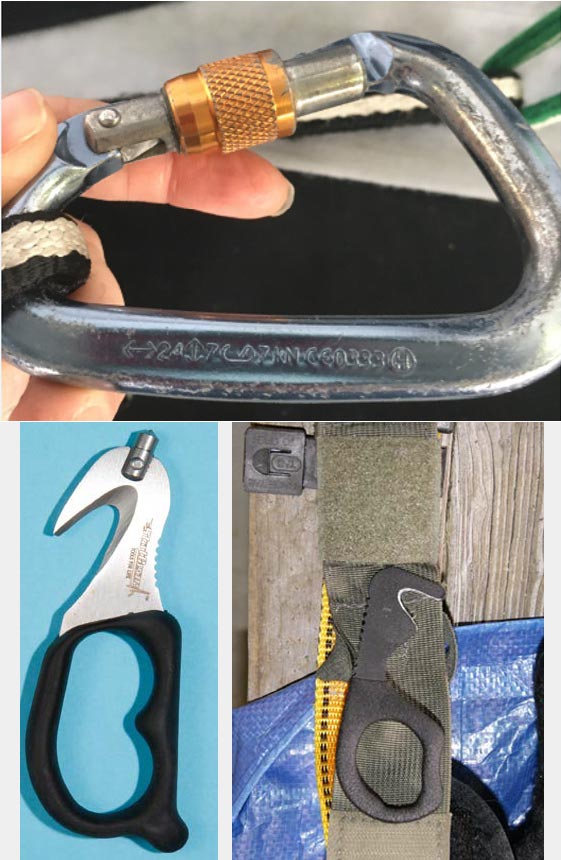

The pilot released his safety belts, and tried but failed to free the front seat passenger from his harness/tether. The five passengers were unable to free themselves from the harness/tether system, and accident investigators concluded that “minimally trained passengers would have great difficulty extricating themselves” from the systems in case of emergency. Each system was equipped “with locking carabiners and an ineffective cutting tool,” the report said.

A tugboat, which was the first vessel to arrive at the accident site, pulled the pilot from the water. Divers entered the water about 15 minutes later to retrieve the passengers, all of whom drowned.

Commercial Pilot Certificate

The accident pilot, 33, held commercial pilot and flight instructor certificates for helicopters with an instrument helicopter rating and an advanced ground instructor certificate. He had 3,100 flight hours, with about 1,430 hours as pilot in command of the AS350. He had completed his initial new hire training with Liberty in March 2016.

The NTSB said the pilot’s qualifications were in compliance with federal regulations and company requirements and were not factors in the accident; neither was the airworthiness of the helicopter, which was manufactured in 2013 and had accumulated 5,510 hours of airframe total time, with no problems detected during two inspections in the month before the accident.

Instead, the NTSB faulted as “inappropriate and unsafe” the decision by Liberty and NYONair “to use locking carabiners and ineffective cutting tools as the primary means for passengers to rapidly release from the harness/tether system.”

The ditching itself was survivable, the NTSB report said, but “the NYONair-provided harness/tether system contributed to the passenger fatalities because it did not allow the passengers to quickly escape from the helicopter.”

The report said the systems were suggested by company pilots and others who had been involved in film production flights and were intended to keep passengers from falling out of the helicopter during doors-off flights.

In the accident helicopter, the systems relied on three different models of locking carabiners, all with gates and locking mechanisms with “a screw-type, threaded locking sleeve that was operated by manually rotating multiple turns to lock or unlock the gate,” the report said.

Cutting Tools

Passengers were provided with cutting tools to be used to extricate themselves from the systems in case of an emergency. They were shown a preflight safety video about the use of the cutting tools, and the pilot said that he provided a briefing, but neither Liberty nor NYONair offered hands-on training, the NTSB said. On-board video from the accident flight showed one rear-seat passenger reaching for his cutting tool and asking “how do I cut this?” The passenger moved toward the open left door but was unable to extricate himself from the helicopter.

The NTSB report also noted that pilots from both companies “were aware that the cutting tools were ineffective for quickly severing the tethers.”

Even if the tools had been effective, the NTSB added, “The cross-routing of the tethers behind passengers in the rear seats would have made it unfeasible for these passengers to access their own tethers during an emergency.”

The accident pilot told investigators that on several flights before the accident, he had moved passengers’ tethers away from the floor-mounted controls and that limited force would be required to pull the fuel shutoff lever out of position. Liberty’s training director said it was “general knowledge among pilots of this type of helicopter to watch for things that could interfere with the floor-mounted controls” and that the issue was discussed during pilot training.

Liberty’s Safety Culture

Liberty began operating some FlyNYON flights in late 2017 or early 2018, the report said, noting that the arrangement coincided with a decline in Liberty’s air tour business and a rapid increase in the aerial photography flights operated by NYONair — an increase so rapid that NYONair could not meet demand using only its own fleet.

The report said that, before the business arrangement began, “core aspects of Liberty’s safety program … had begun to deteriorate,” with its withdrawal in 2017 from an air tour industry group and the departure of the company’s director of safety. The safety director’s successor said he had received no training other than a briefing from the prior safety director.

Neither Liberty nor NYONair had a safety management system, and the report said that ineffective safety management at both companies led to “a lack of prioritization and mitigation of foreseeable risks.”

In addition, the report said that Liberty’s managers demonstrated a “repeated lack of involvement in key decisions” concerning the FlyNYON flights and that they “allowed NYONair personnel, particularly NYONair’s chief executive officer, to influence core aspects of the operational control of those flights.”

Liberty’s pilots recognized some risks associated with the FlyNYON flights, including the inadequate cutting tools and the potential for the harness/tether systems to become entangled with the floor-mounted flight controls, and took informal steps to address those concerns. Their efforts were not managed at the organizational level, however.

For example, Liberty’s safety officer and chief pilot told NYONair managers that they were concerned about the harness/tether systems and that they wanted specific harnesses for safety reasons; NYONair said those concerns would be addressed.

“However, … implementing the request became deprioritized over time, and NYONair management and other employees came to regard the Liberty pilots’ concerns about the harness/tether system as superfluous and not urgent,” the report said.

The document added that eventually, NYONair’s CEO told the Liberty pilots to stop requesting more harnesses of the type they considered safer because there was no safety issue with the harness/tether systems that were used in the accident helicopter.

The report also noted that when Liberty pilots canceled one flight because of cold weather and delayed another until passengers could be fitted with a harness that the pilots considered the better safety choice, the NYONair CEO “responded by chastising them for hurting his brand, and he deprioritized their concerns by deciding that they were unrelated to safety. This contributed to a polarization of attitudes and reduced cooperation between the Liberty pilots and NYONair management on safety matters.”

FAA Surveillance

The report noted that the FAA principal operations inspector for Liberty helicopters conducted no additional surveillance after learning that Liberty had taken on FlyNYON flights. The inspector “failed to ensure that Liberty was appropriately managing the risks associated with the significant change in operations,” the report said.

The report also cited both Liberty and NYONair for their “exploitation” of a provision of the FARs that allowed aerial photography flights to be operated under Part 91. The companies sought to “avoid any indication that the flights may be commercial air tours, which would be subject to additional FAA requirements and oversight,” the report said.

Safety Recommendations

The report included 14 safety recommendations, including 10 recommendations to the FAA. Among them was a recommendation calling for changes in the process used by the FAA to review any plans to modify an aircraft supplemental passenger restraint system (SPRS) to include an FAA review of SPRS design, manufacture, installation and operational considerations, including the potential for passengers to become entangled in the system during emergency egress.

Other recommendations to the FAA called on the agency to review the activation system designs of approved emergency flotation systems for helicopters to identify deficiencies that might preclude their proper deployment, to require commercial air tour operators to implement a safety management system, and to ensure that the FARs definitions of aerial work and aerial photography specify “only businesslike, work-related aerial operations, as originally intended.”

Other recommendations said that Airbus Helicopters should modify the floor-mounted fuel shutoff lever in AS350 helicopters “to protect it from inadvertent activation due to external influences” and that the European Union Aviation Safety Agency should require AS350 owners and operators to incorporate those change.

The recommendations to Liberty and NYONair called on both companies to establish a safety management system and to train employees to recognize “signs of impairment and intoxication in passengers and to deny those passengers boarding, when appropriate.”1

This article is based on NTSB Accident Report NTSB/AAR-19/04, “Inadvertent Activation of the Fuel Shutoff Lever and Subsequent Ditching; Liberty Helicopters Inc., Operating a FlyNYON Doors-Off Flight; Airbus Helicopters AS350 B2, N350LH; New York, New York; March 11, 2018.”

Note

- The report said the front seat passenger was intoxicated but that the investigation could not determine whether his intoxication contributed to his inadvertent activation of the fuel shutoff lever. An existing FAA regulation prohibits the carriage of an intoxicated or impaired passenger, but neither Liberty nor NYONair had a documented policy or guidance materials to help employees identify affected passengers, the report said.

Featured image: U.S. National Transportation Safety Board

Video: U.S. National Transportation Safety Board

Flight path: U.S. National Transportation Safety Board

Front seat tether: U.S. National Transportation Safety Board

Carabiner and cutting tools: U.S. National Transportation Safety Board and U.S. Federal Aviation Administration

Accident aircraft: Anna Zvereva | Wikimedia CC-BY-SA 2.0