With pilots reporting an increasing number of sightings of unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) aircraft, authorities are exploring new ways to tell rogue operators to keep their distance — with an emphasis on educating new operators and enforcing existing laws.

At the same time, representatives of model airplane enthusiasts say that reported sightings of a small UAS or a model aircraft are often just that — sightings — and do not constitute “close calls.”

The Academy of Model Aeronautics (AMA), which represents 180,000 people who fly model aircraft for recreation or educational purposes, issued a detailed analysis1 of U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) data on 765 reported UAS sightings from Nov. 13, 2014, through Aug. 20, 2015 (see “Reports of UAS Aircraft Sightings”),2 concluding that only about 27 were explicitly identified as near-midair collisions. Some reports specifically quoted pilots as saying the event was not a near-midair collision, but most said nothing on the subject.

The FAA data, made public in late August, included reports by pilots, air traffic controllers and others of possible sightings of UAS aircraft.

Almost daily, news reports describe some of the most serious encounters, based on information from law enforcement authorities or witnesses.

For example, on June 24, officials fighting a wildfire in California’s San Bernardino Mountains called off flights by a McDonnell Douglas DC-10 and two smaller airplanes loaded with retardant after an incident commander saw what was described as a “hobby drone” near the drop site. A report in the Los Angeles Times said the incident forced air drops to be halted two hours ahead of schedule and quoted an official as saying the fire grew as a result. Authorities were unable to locate the UAS operator, the report said.3

In a July 2014 incident, a UAS aircraft was flown within 800 ft (244 m) of a New York City Police Department helicopter. According to a report in The New York Times, the helicopter pilot told officers that the UAS had “gotten in the way” as he flew the helicopter near the George Washington Bridge. The UAS then landed nearby, on a parked vehicle, and responding officers arrested two men in possession of two UAS aircraft and two remote controls, the report said. The men were charged with reckless endangerment.4

According to the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Office of Inspector General — which announced in late August that it plans to audit the FAA’s approval and oversight of UAS operations — more than 60 UAS-related reports are submitted to the FAA each month.

The FAA count is higher, and the agency said 650 UAS sightings were reported between Jan. 1 and Aug. 9 of this year, compared with 238 for all of 2014.

In a statement issued later in August along with data on the 765 reported November-through-August UAS sightings, the agency stressed that many of the reports involved sightings too distant to constitute a conflict with the reporting pilot’s aircraft — and, in some cases, too distant even to be sure that the object was, in fact, a UAS aircraft. Other reports described uncomfortably close encounters that required the reporting pilot to change course.

In a statement issued later in August along with data on the 765 reported November-through-August UAS sightings, the agency stressed that many of the reports involved sightings too distant to constitute a conflict with the reporting pilot’s aircraft — and, in some cases, too distant even to be sure that the object was, in fact, a UAS aircraft. Other reports described uncomfortably close encounters that required the reporting pilot to change course.

Some of the FAA’s preliminary reports note that law enforcement authorities were notified of the occurrences, but typically, they were unable to locate the UAS operators — or even to spot a UAS aircraft.

“Because pilot reports of unmanned aircraft have increased dramatically over the past year, the FAA wants to send a clear message that operating drones around airplanes and helicopters is dangerous and illegal,” the agency said in a statement accompanying release of its list. “Unauthorized operators may be subject to stiff fines and criminal charges, including possible jail time.”

An FAA spokesman said the agency is “exploring what additional actions we may be able to take using our statutory authority and what we may need additional authority to do.”

‘More Complex Picture’

AMA said that its analysis of the FAA data, released in mid-September, yielded “a more complex picture of … UAS activity.”

The AMA analysis added that some of the occurrences on the FAA’s list involved military UAS aircraft, including reports of several crashes, or UAS operated by public entities. Other listed occurrences involved UAS aircraft being flown above stadium events, power plants and other high-risk areas, AMA said, adding that these sightings “raise different concerns from pilot sightings. Still other occurrences involved observations of civilian UAS aircraft being flown in accordance with the rules and representing no threat to other aircraft, and some involved flying objects other than UAS aircraft.

“Many things in the air — from balloons and birds to model rockets and mini-blimps — are mistaken for, or reported as, drone sightings, even when they are not,” AMA said. “One pilot in Minnesota even reported seeing something that ‘resembled a dog.’”

To provide a more accurate picture, future FAA reports should sort out occurrences that do not involve civilian UAS or model aircraft, and those in which UAS operators are reported to authorities even though they are following the rules, AMA said.

‘Very Few Fines’

AMA said that, although it questions some of the FAA data, it endorses the FAA’s call for aggressive enforcement of existing rules.

Both AMA and the Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International (AUVSI) noted that the FAA currently has the authority to issue civil penalties of up to $25,000 for careless and reckless behavior and that some local jurisdictions also have criminal laws that would allow prosecution of careless and reckless operators.

“There have been very few instances in which rogue operators have been fined for acting irresponsibly,” said AUVSI President and CEO Brian Wynne. “AUVSI wants to see the FAA greatly step up its enforcement of these penalties and use its current authority to levy hefty fines on anyone who operates a UAS or model aircraft in this way. …

“Stricter enforcement will not only punish irresponsible operators, it will also serve as a deterrent to others who may misuse UAS technology.”

Both organizations urged the FAA to finalize its proposed small UAS rules — for aircraft weighing less than 55 lb (25 kg) — as soon as possible, with AUVSI noting that, after the rules are in place, all small UAS operators would be required to “follow the safety programming of a community-based organization [such as AMA] or abide by new UAS rules for commercial operators. Once the rules are finalized, consumers will no longer be able to fly without any oversight or education.”

The new rules, proposed in February, will not apply to operators of model aircraft, who will be required to continue to comply with an existing law specifying, among other things, that their models must be flown only for recreational use and only in accordance with a nationwide community-based organization’s safety guidelines.

Michael Braasch, an electrical engineering professor at Ohio University and an expert in UAS operations, agreed, adding that “harsh, attention-grabbing federal penalties are needed for those that flagrantly violate the rules (e.g., purposely flying near manned aircraft without permission).”

He noted that such penalties — including thousands of dollars in fines or prison terms, or both — are regularly administered to people convicted of shining laser beams into cockpits.

Too many reported encounters between manned aircraft and UAS aircraft have not been referred to local law enforcement authorities, AMA said, adding that, “While not every report is a serious safety risk, or even someone behaving irresponsibly, the only way to identify the truly careless and reckless operators and to learn the facts about what happened is better communication and coordination with local law enforcement.”

Safety Education

The FAA and government and industry groups agree that education is key to reducing incidents of careless and reckless operation of model aircraft and small UAS aircraft, as well as violations of restricted airspace.

“Education is critical,” Wynne said. “Whether someone is flying a commercial UAS or a model aircraft for recreational purposes, unmanned aircraft shouldn’t fly close to airports, close to manned aircraft, near wildfires or above 400 ft. These are common sense guidelines, but as access to the technology increases, many new UAS enthusiasts may not be taking the time to understand where they should and should not fly. This behavior can be changed through better education.”

Acting in accordance with that belief, AUVSI, AMA and the Small UAV Coalition, in partnership with the FAA, founded the Know Before You Fly program,5 aimed at providing guidance on the responsible use of UAS and model aircraft, in December 2014. Several other organizations, including the National Air Traffic Controllers Association, joined the effort this year.

“Remain well clear of and do not interfere with manned aircraft operations, and you must see and avoid other aircraft and obstacles at all times,” the program says in its guidance for recreational users. “Contact the airport or control tower before flying within five miles of an airport.”

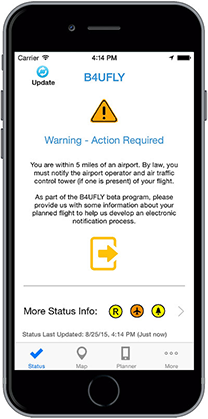

The FAA introduced one component of the Know Before You Fly program — the B4UFLY smartphone application — in August for testing by 1,000 users of model aircraft and small UAS. The application is designed to tell users if the location they have chosen for flight is safe and legal, and also includes links to other UAS information sources and regulatory information.

The FAA introduced one component of the Know Before You Fly program — the B4UFLY smartphone application — in August for testing by 1,000 users of model aircraft and small UAS. The application is designed to tell users if the location they have chosen for flight is safe and legal, and also includes links to other UAS information sources and regulatory information.

Another educational effort is the “If You Fly, We Can’t” campaign by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Forest Service, which aims to stop model aircraft and UAS operators who might be considering sending their aircraft into a wildfire area.

“Flying drones or UAS … within or near wildfires without permission could cause injury or death to firefighters and hamper their ability to protect lives, property and natural cultural resources,” the campaign’s posters say. “Fire managers may suspend aerial firefighting until unauthorized UAS leave the area, allowing wildfire to grow larger.”

These programs, while helpful, “are not sufficiently wide reaching,” said Ohio University’s Braasch. “The FAA and/or other cognizant federal government agencies need to engage in a much more widespread media campaign. … A public service announcement campaign broadcast on radio and TV would stand a better chance of reaching the folks who are unaware that their actions are potentially dangerous.”

Warning Labels

Braasch also suggested that hobby drone manufacturers place large warning labels on the face of the box, “and not just in the legal fine print at the beginning of the user manual,” to help educate their customers about their responsibilities.

AMA said it is working with manufacturers and distributors to include more safety information in product packaging or at the point of sale. For example, six manufacturers and distributors say they will include Know Before You Fly information with their products, and one chain displays the material in all of its stores.

In addition, AMA said that one quadcopter manufacturer asked sellers to distribute Know Before You Fly brochures to purchasers of its aircraft, and has developed product geo-fencing features that use global positioning system information to create boundaries defining areas where the aircraft cannot be flown.

Geo-fencing can help reduce the number of inadvertent flights into restricted airspace, Braasch said, but it is “not a magic-bullet perfect solution” and operators who are intent on circumventing the boundaries can find ways to do so.

Wynne added that geo-fencing and other technological solutions “are no substitute for education,” including programs such as Know Before You Fly.

“There’s a longstanding principle in aviation that places responsibility for safety in the hands of the operator of an aircraft, whether it’s manned or unmanned,” he said. “People need to know where they should and shouldn’t fly, and this responsibility shouldn’t be outsourced to manufacturers or technology.”

‘No Real Data’

As for the damage that could be done if a small UAS or model aircraft struck an airplane, an FAA spokesman said “there’s no real data on the [effects of an] impact of a UAS equipped with a typical battery.”

Research in that area is planned, he said.

Braasch said that, although some small UAS advocates have called for a new “micro” category of aircraft that weigh less than 2.0 kg (4.4 lb) and are subject to minimal regulation, “a 2.2-kg hunk of plastic and metal can certainly do serious damage to an aircraft. The proof of this lies in historical bird strike data for so-called large birds (e.g., vultures).”

Notes

- AMA. A Closer Look at the FAA’s Drone Data. Sept. 14, 2015.

- FAA. FAA Releases Pilot UAS Reports. Aug. 21, 2015.

- Serna, Joseph; Esquivel, Paloma; Mozingo, Joe. “Lake Fire Grew After Private Drone Flights Disrupted Air Drops.” Los Angeles Times. June 25, 2015.

- Feuer, Alan. “2 Arrested After Drone Flies Close to a New York Police Helicopter.” The New York Times, July 8, 2014.

- Available online at <knowbeforeyoufly.org>.

Featured image: © piotr_roae|Adobe Stock

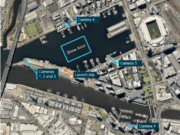

No Drone Zone: U.S. Federal Aviation Administration

B4UFLY screen: U.S. Federal Aviation Administration