Canada, the first country in the world to require its aviation community to implement safety management systems (SMSs), should expand the requirement to all commercial operators, a committee of the Canadian Parliament says.1

The House of Commons Standing Committee on Transport, Infrastructure and Communities said, in a report released in late June detailing its review of aviation safety in Canada, that SMS — required since 2008 for major airlines and airport operators and since 2009 for air navigation service providers — should also be mandatory for the air taxi sector and other commercial operators.

The report said that Transport Canada (TC) should pair the SMS requirement with more on-site safety inspections. Poor results from SMS audits, including comments from whistleblowers, should serve as “a flag for prioritizing on-site inspections,” the report said. In addition, the document called for policies on whistleblowers to be reviewed to ensure adequate protection for people who draw attention to on-the-job safety issues.

Other recommendations said that the Canadian government should ensure that SMSs are “accompanied by an effective, properly financed, adequately staffed system of regulatory oversight: monitoring, surveillance and enforcement supported by sufficient, appropriately trained staff,” and that TC should review training processes and training materials to ensure that civil aviation inspectors have the resources needed to effectively perform their jobs.

Divided on the Merits

During hearings tied to the safety review, lawmakers heard from witnesses who were sharply divided over the merits of SMS.

The committee report quoted Kathleen Fox, chair of the Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB), as saying that “when properly implemented, safety management systems can help any commercial operator in any mode of transportation better manage its safety risk.”

John McKenna, president and CEO of the Air Transport Association of Canada, also endorsed SMS, telling the committee that the presence of SMS in the aviation industry has “fostered within companies a safety culture that already existed but that is now more ubiquitous.”

Virgil Moshansky — a Canadian judge who led an inquiry into the fatal 1989 crash of an Air Ontario Fokker F-28 near Dryden, Ontario,2 and who, in his report on the accident, recommended widespread implementation of SMSs in Canadian aviation — told the committee that SMS “was never intended to replace direct operational oversight.”

Moshansky and other committee witnesses said that SMSs should be used as supplements to regulatory compliance inspections and other methods of ensuring aviation safety, the report said.

Methods of introducing SMS into Canadian aviation have occasionally been criticized for taking too long and lacking adequate training for inspectors, the report said.

Fox suggested that TC should review the “balance between inspections and audits for compliance with regulations … and audits of the effectiveness of safety management systems.” She also recommended the expansion of SMS to all operators, arguing that SMS “can go even further than strict compliance with regulations, in terms of helping companies manage safety.”

Although Fox and other supporters of SMS said that the requirements could be adapted for smaller operators, TC officials said they were concerned that requiring them to implement an SMS could present an excessive burden and that other actions might be more effective in improving safety in that sector, the report said.

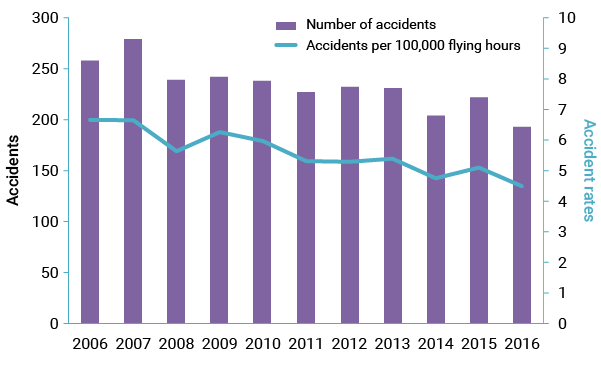

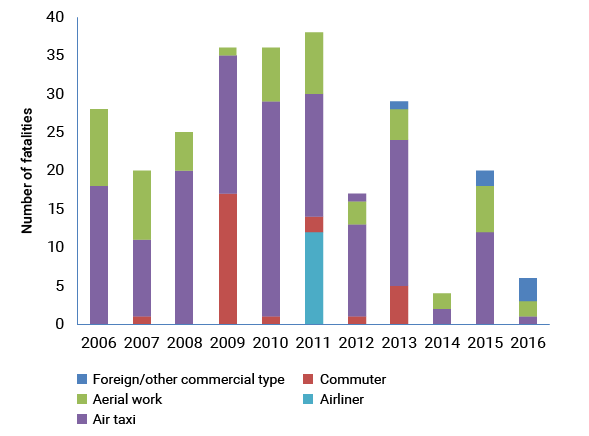

The committee’s review also addressed numerous other aspects of aviation safety, noting declines in recent years in accidents and accident rates involving Canadian-registered aircraft. Overall, the number of aircraft accidents involving Canadian-registered aircraft decreased from 258 accidents in 2006 to 193 accidents in 2016 (Table 1). Commercial aviation accidents declined from 128 accidents in 2006 to 62 accidents in 2016. Data showed there were 242 fatalities in commercial aviation accidents during that period, about 60 percent of which were associated with air taxi operations (Figure 2).

Figure 1 — Accidents and Accident Rates Involving Canadian-Registered Aircraft (per hours flown, excluding ultralights and other aircraft types), 2006–2016

Source: Canadian House of Commons

Figure 2 — Fatalities in Commercial Aircraft Accidents in Canada by Operator Type, 2006–2016

Source: Canadian House of Commons

Despite the nation’s “strong and improving” safety record,” the report said, “some stakeholders have voiced concerns that past safety performance may not be indicative of future performance.”

‘Fatigue is Omnipresent’

Among the issues that concern them is pilot fatigue, the report said, adding, “When discussing safety in any mode of transportation, the question of fatigue is omnipresent.”

Fox told the committee that in all accident investigations, the TSB determines whether fatigue was present and whether it played a role in the accident.

Canadian Aviation Regulations establish maximum duty hours for flight crews, depending on a variety of conditions. Generally, a commercial aircraft with a two-pilot flight crew is permitted to fly up to 14 consecutive hours in any 24-hour period, although that limit may extend to 20 hours in cases when an augmented flight crew includes additional pilots to take over so that others may rest.

In March, TC proposed amending the regulations to make duty times dependent, in part, on the time of day and on whether the pilots are operating under visual flight rules or instrument flight rules.

The report noted that representatives of the Air Canada Pilots Association and the Airline Pilots Association, International told the committee that those proposed changes do not go far enough in addressing fatigue and said they are concerned that airlines might use their fatigue risk management systems — based on scientific principles and operational experience to monitor fatigue-related safety risks — to avoid compliance with maximum duty time limits.

Some operators, especially those in the helicopter industry and those with operations in Northern Canada, said the nature of their operations may complicate efforts to comply with flight time and rest requirements, in part because time zones are closer together in the North and because many pilots fly to work from other parts of the country.

The report said that, to “ensure that an evidence-based approach to fatigue management is undertaken using the latest scientific approaches and recognizing the diversity of Canadian operations,” the committee recommended that TC solicit comments on its proposed changes in fatigue regulations, and “find ways to take into account the specific operating conditions of certain regions.”

The committee identified another issue affecting Northern Canada as the “antiquated air infrastructure” in the region, as well as regulations that many consider unsuitable for flight operations there.

“For example, the committee was told that Canada’s North, which accounts for about 40 percent of the country’s area, has roughly 100 runways, 10 of which are paved,” the report said. “In addition, these small airports often do not have the range of services available at other Canadian airports.”

The report noted that the Northern Air Transport Association (NATA) had cited several specific problems:

- “The lack of long, paved runways in most northern airports,” which results in the use of aging aircraft “because the ‘gravel kits’ for the commonly used jet aircraft have not been manufactured for close to 30 years”;

- “The lack of 24-hour weather information, [which] requires operators to have several backup plans in case of changing weather conditions”; and,

- The use of older instrument approach procedures, which result in numerous missed approaches.

The report quoted NATA Executive Director Glenn Priestley as saying that these problems combine to increase risk in air operations in the North.

Similar observations were made in a 2016 review of the Canada Transportation Act and in a May 2017 report by the auditor general of Canada on civil aviation infrastructure in the North.

“In his testimony before the committee, the auditor general said that Transport Canada did not have any plan to address infrastructure needs, even though these issues go back 10 years,” the report said.

Priestley also told the committee that TC does not understand air services in Canada’s North, the report said, adding, “He believes this has resulted in ‘a set of regulations that will provide no measurable improvement in overall system safety but will increase costs.”

He told the panel that TC should develop a plan to identify all issues affecting the North and how they should be addressed, and the committee echoed that sentiment with a recommendation calling on TC to “develop a plan and a timeline to address the specific operating conditions and infrastructure needs of airlines serving Northern Canada and small airports.”

Flight Attendant Staffing

Similarly, the report called on the government to consult stakeholders and subject experts about the revision of its current requirement of a 50-1 ratio of passengers to flight attendants, “while keeping the security of Canadians as a top priority.”

The report noted that although the 50-1 ratio is the most common ratio worldwide, including on U.S. and European airlines, Canadian operators had been subject to a 40-1 ratio — until August 2015, when the requirement was changed.

The report quoted labor union representatives as endorsing the return of the previous, lower ratio, arguing that in Canada, flight attendants have primary responsibility for the evacuation of passengers and response to a fire inside an aircraft. Fire crews are not authorized to enter, the report said.

Slow Going

Fox told the committee that the TSB is concerned about the slow response from TC to many TSB safety recommendations.

Since 1990, when the TSB was established, it has investigated 973 aviation accidents or incidents and issued 181 safety recommendations, most of them to TC but some to other regulators, air operators and manufacturers. Those receiving a TSB recommendation are not required to implement it, but federal officials are required to inform the TSB of action they plan to take or, if no action is planned, to explain why.

TSB typically rates responses to its recommendations on a scale ranging from “fully satisfactory” to “unsatisfactory,” and Fox told the committee that TC’s responses to 32 of TSB’s aviation-related recommendations have not yet received “fully satisfactory” ratings, even though the recommendations were issued more than 10 years ago.

The report quoted TC Assistant Deputy Minister, Safety and Security Laureen Kinney as conceding that TC had been slow to act on a number of recommendations but that in some cases, technology had rendered the recommendations obsolete, and in other cases, the recommendations were too complex to be implemented.

The report said that “implementing many of the TSB recommendations takes time, especially because regulatory amendments are needed” and proposed that TC “establish an expedited process for responding” to the backlog of TSB recommendations and adopt an enhanced reporting system “to prevent recommendations from languishing, without action.”

Additional recommendations contained in the report include:

- That the minister of transport examine the best practices for flight training, “striking a balance between in-flight and simulator-based training and certification for pilots.”

- That the government implement recommendations from the TSB and the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) calling for creation of 300-m (984-ft) runway end safety areas (RESAs). Current Canadian standards are for RESAs of half that length.

- That TC ask ICAO to conduct an audit of Canada’s civil aviation oversight system, and that TC conduct its own air safety review and report its findings to Parliament.

Notes

- Canadian House of Commons Standing Committee on Transport, Infrastructure and Communities. “Aviation Safety in Canada.” June 2017.

- The March 10, 1989, accident killed 24 of the 69 passengers and crew and injured the other 45 people in the F-28, which crashed less than a minute after takeoff from Dryden Regional Airport in Ontario. Moshansky’s Commission of Inquiry cited a series of problems, including that the airplane was not deiced before takeoff because deicing was prohibited when aircraft engines were running; the engines were left running because the airplane’s auxiliary power unit was unserviceable and no external power unit was available for an engine re-start. The commission concluded that the captain was ultimately responsible for having taken off on a slush-covered runway in an airplane with snow on its wings; the four-volume final report also cited the air transportation system, which “failed him by allowing him to be placed in a situation where he did not have all the necessary tools that should have supported him in making the proper decision.”

Featured image: © niyazz | Adobe Stock

Resolute Bay Airport: © Timkal | Wikimedia CC-BY-SA 3.0