An overemphasis on assessing aircraft operators’ safety management systems (SMS) at the expense of enforcing regulatory compliance is creating new risks that unsafe conditions and practices might go unnoticed, the Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) says.

The agency cautioned that the risk of aviation accidents could increase if Transport Canada (TC) “does not adopt a balanced approach that combines inspections for compliance with audits of safety management processes.”

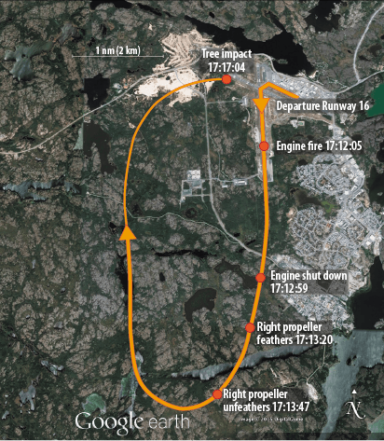

The TSB made the observations in its final report on an Aug. 19, 2013, accident involving a Buffalo Airways Douglas DC-3C shortly after takeoff from Yellowknife Airport in Canada’s Northwest Territories for a scheduled passenger flight to Hay River. None of the 24 people in the DC-3 was injured in the emergency gear-up landing, which followed the discovery of a fire in the right engine.

In the report, issued in April, the TSB said that a fatigue crack led to the failure of a cylinder in the right Pratt and Whitney R1830-92 Twin Wasp 14-cylinder radial engine and the subsequent engine fire. Although the right propeller’s feathering mechanism was activated, the propeller never became fully feathered, probably because of a seized bearing in the feathering pump, the TSB report said. Investigators were unable to determine the cause of the fatigue crack.

The windmilling propeller resulted in increased drag, and that condition, along with the DC-3’s weight — which exceeded maximum certified takeoff weight — contributed to the airplane’s inability to maintain altitude, the report said. The airplane struck trees and the ground short of the landing runway.

The TSB concluded that Buffalo Airways “did not have an effective … SMS in place to identify and mitigate risk in its operations” and that TC’s oversight failed to identify those risks.

Buffalo Airways, in operation since 1970, conducts passenger and cargo air taxi and airline operations throughout the Canadian Arctic. Its airline fleet is made up of 10 aircraft. In recent years, the operation has been the subject of a cable television series that explores the adventures of what the network describes as “a renegade Arctic airline.”1

Buffalo Airways maintains a company operations manual (COM) for its airline operation. The document, approved by TC, is intended to provide employees with the company’s guidance on the handling of normal and emergency procedures.

The TSB report described one section of the manual that details procedures for checking in passengers and cargo. Those procedures call for an aircraft weight and balance calculation to be performed for each flight, using standard passenger weights “unless it is apparent that the passenger does not fit the standard weight,” the report said. Carry-on baggage in excess of 8 lb (4 kg) must be weighed, according to the COM.

In March 2010, Buffalo Airways was recognized by TC as an “SMS-compliant” company, and the accident report said that the operator uses “a proactive and a reactive risk assessment reporting system … [to] allow the company to identify issues that may expose the company to risk. Once identified, these issues are assessed and an internal corrective action plan may be implemented to address and correct them.”

During the year preceding the accident, neither the proactive plan nor its reactive counterpart identified any issue “relating to operational control, weight and balance or calculated aircraft performance to have been of concern,” the report said.

Weight and Balance

The airplane, manufactured in 1942, originally was a military transport C-47B and was converted in 1975 for use in civil aviation. Buffalo Airways has owned the airplane since 1994.

TC had authorized Buffalo Airways’ weight and balance control program, and the company was exempt from a Canadian Aviation Regulations (CARs) requirement that large aircraft be weighed, and their weight and balance reports updated, every five years. Instead, the company’s program called for recording aircraft weight and balance amendments whenever there was a change in an aircraft’s empty weight, the report said.

Nevertheless, the report said, “there were no weighing frequency intervals listed or used in the MCPM [the approved maintenance organization’s Maintenance Control Policy Manual],” and the last recorded weighing of the DC-3 was in 1990.

The airplane had a maximum certified takeoff weight of 26,200 lb (11,884 kg). The day of the accident, although the DC-3 was configured for 28 passengers (the maximum allowed), it carried 21 passengers and one flight attendant, along with two flight crewmembers. It also carried 2,707 lb (1,228 kg) of fuel — the equivalent of 1,702 L (450 gal) — and was “loaded with cargo,” the report said.

“The [weight and balance] calculation for the occurrence flight had been started by the [first officer] but not completed prior to departure,” the report added. “It was common practice to complete the OFP [operational flight plan] and weight and balance en route. … Data from the incomplete OFP indicated a takeoff weight of 21,844.2 lb [9,908.5 kg]. An actual takeoff weight was not determined.”

The report said that the passenger manifest did not include the weights of the passengers or their baggage, and that neither had been weighed during check-in, although company procedures called for weighing.

A cargo manifest, which was not made available to the flight crew, listed a cargo weight of 1,071 lb (486 kg).

In addition, the report said that a review of completed OFPs from the company’s other flights “indicated the use of passenger weights that were adjusted to facilitate and maintain the weight and balance calculation within limits.

When TSB investigators calculated the operational takeoff weight for the accident flight — using standard passenger weights specified by the company’s operations manual, OFP data and actual cargo weight — they determined that the takeoff weight was 27,435 lb (12,445 kg), or 1,235 lb (560 kg) more than the maximum certified takeoff weight. The center of gravity was within the manufacturer’s limits.

“In this occurrence, a complete and accurate weight and balance report was not calculated prior to takeoff,” the TSB report said. “As the aircraft’s weight and balance had not been updated since 1990, using actual passenger and cargo weights may not have produced an accurate takeoff weight. As such, the crew would not be able to determine accurately the aircraft’s performance capabilities during a normal takeoff. … [A]ircraft operating above the maximum certified takeoff weight (MCTOW) experience a serious degradation in climb performance when experiencing an engine failure with a windmilling propeller.

“Additionally, the company did not have the capability to demonstrate how its aircraft could meet the CARs net takeoff flight path (NTOFP) performance requirements, despite stating this requirement within its operations manual. This puts the safety of flights at risk.

“If companies do not adhere to operational procedures in their operations manual, there is a risk that the safety of flight cannot be assured.”

Ineffective SMS

Although the company had an SMS, the TSB found “indications that the organizational culture at Buffalo Airways was not supportive of a system that required the organization to take a proactive role in identifying hazards and risks,” the report said.

For example, the practice of in-flight adjustments of weight and balance calculations to indicate compliance with limits was “well known and accepted by senior management,” the report said.

Because takeoff performance calculations were not done, even though they were required by the CARs and specified by the COM, and an assessment of obstacle clearance in case of an engine failure had not been done, flight crews may not have fully understood the risks of overweight operations, the report added.

“Previous success in operating the aircraft overweight was likely taken as assurance of future performance without consideration being given to aircraft performance in the event of an emergency,” the TSB said, adding that it was “highly unlikely that these unsafe practices would be reported through, or addressed by, the company’s SMS.”

The TSB report said that Buffalo frequently challenged TC surveillance findings and “initially did not take responsibility for the issues identified” by TC.

“The overall picture that emerged from this investigation is of an organization that met the basic requirements of regulations, and then only when pushed by the regulator,” the report said.

Inspections and Audits

Before the implementation of SMS, TC Civil Aviation’s oversight of Buffalo Airways consisted of a combination of inspections and audits, the report said, describing “a cycle of repeated inspection findings during which inspections would identify unsafe conditions, the company would take action to address them and, sometime later, the conditions would recur.”

TC performed its first SMS assessment at the airline in 2009. The assessment was designed to confirm that Buffalo Airways had, in fact, implemented an SMS.

During its investigation of the accident, the TSB reviewed TC’s surveillance activities at Buffalo Airways and company responses during the three years before the event. In that time, there had been four surveillance activities: one SMS assessment, one process inspection and two program validation inspections (PVIs); all four activities focused on required elements of the company’s SMS.

The surveillance process requires operators to respond to TC findings by submitting corrective action plans (CAPs) that “provide the operator’s analysis of the reasons underlying the deficiency and provide an action plan to address them,” the TSB report said. TC inspectors then evaluate the CAPs; if they reject a CAP, it is returned to the operator for revision or it forms the basis for a notice of suspension of the company’s air operator certificate.

The TSB report said that its review of the CAP paperwork revealed a picture of “an operator at odds with the regulator.”

The report added, “In the initial CAP submissions for the December 2011 PVI, the operator took exception to multiple findings, requesting clarification as to the regulatory basis for the deficiencies identified by TC and explicitly questioning the competence and motivation of TC inspectors. TC rejected these initial CAPs, noting that the CAP process was not the appropriate venue for ‘repeated diatribes against Transport Canada.’ Buffalo Airways revised the CAPs and they were accepted by TC.”

Two subsequent surveillance activities identified the weight and balance control issues that were discussed in the accident report, the TSB said.

Flexible Oversight

TC conducted four surveillance activities at Buffalo Airways in the three years before the accident, and all four focused on required SMS components, the TSB said. There was no record of TC oversight activity that examined compliance with the CARs or Commercial Air Service Standards, and the surveillance activities did not identify the problems that became apparent during the investigation — overweight operations and the lack of required performance calculations.

After the investigation, TC conducted two additional surveillance activities, examining the company’s operational control system by using a tool that was designed to verify compliance with regulations. This method usually is used on companies that are not required to have an SMS, the report said.

“While a move towards SMS has great potential to enhance safety by encouraging operators to put in place a systemic approach to proactively manage safety, the regulator must also have assurances of compliance with existing regulations, particularly for operators that have demonstrated a reluctance to exceed minimum regulatory compliance,” the report said.

The document added that if TC does not “adopt a balanced approach that combines inspections for compliance with audits of safety management processes, unsafe operating practices may not be identified, thereby increasing the risk of accidents.”

The Aftermath

After the accident, Buffalo Airways began weighing individual passengers and baggage and calculating weight and balance before departure. The company also arranged for the development of NTOFP charts and took several steps intended to ensure regulatory compliance.

In February 2015, TC approved a revised Buffalo Airways COM that led to several other changes within the company, including the appointment of a new accountable executive and a reorganization of management that calls for the SMS manager to report directly to the accountable executive.

This article is based on TSB Aviation Investigation Report A13W0120, “Engine Failure After Takeoff and Collision With Terrain; Buffalo Airways Ltd., Douglas DC-3C, C-GWIR; Yellowknife Airport, Northwest Territories; 19 August 2013.”

Note

- History (Canada). Ice Pilots NWT.

Featured image: © Anson Chappell | Flickr

Flight path: Transportation Safety Board of Canada