On Aug. 14, 2013, an Airbus A300-600 freighter experienced a controlled flight into terrain (CFIT) fatal accident during a localizer non-precision approach to Runway 18 at Birmingham (Alabama, U.S.) Shuttlesworth International Airport (“False Expectations,” ASW, Feb. 2015). The National Transportation Safety Board ultimately concluded that pilot error, specifically “the flight crew’s continuation of an unstabilized approach and their failure to monitor the aircraft’s altitude during the approach,” was the probable cause of the crash, which killed both crewmembers and destroyed the airplane.

The cockpit voice recorder revealed a haunting revelation about the content of the crew’s arrival briefing — it was perfect. Or was it? There was certainly a lot of talking by the pilot flying (PF) as he dutifully “ticked all the required boxes,” but no discussion regarding the relevant threats or countermeasures that could have averted disaster. The fatigued crew chose to fly a seldom performed, non-precision approach at night to a short runway with limited lighting; the weather forecast suggested an unpredictable cloud ceiling. This is one more example of an all-too-common thread in recent industry accidents: the loss of flight path and situational awareness due to onset of high crew workload as a result of rapidly changing conditions.

We have spoken to numerous U.S. and international air carriers about the content of their departure and arrival briefings and have found most to be strikingly similar. The commonality is a decades-old briefing method that has neither adapted to next generation flight decks nor incorporated breakthroughs in our understanding of human cognition. Today’s typical standard operating procedure (SOP) briefing is simply too long (due to years of adding more and more items determined to be ”too important not to discuss”). Additionally, briefings have become one-size-fits-all solutions serving as repositories for redundant verbal crew crosschecks of highly automated, highly reliable systems. Finally, too often they are one-sided conversations that lack involvement from the crewmember that recent industry accident trends indicate will play a primary role in maintaining safety margins: the pilot monitoring (PM).

After the Birmingham accident, Alaska Airlines reviewed its departure and arrival briefings and found they were equally inadequate. As a result, we decided to conduct a comprehensive study of our crew briefings that started with a review of our voluntary safety data (advanced qualification program, aviation safety action program, flight operational quality assurance, and line operations safety audit [LOSA]). We wanted to see if we could find a link between the content of our own lengthy, one-sided, “box checking” type briefing and the safety deficiencies noted in the data. What we found was astonishing. There was not only a clear connection between crew errors and undesired aircraft states with the quality and content of the briefings that preceded them, but also a disconnect between our SOP briefing requirements and line pilot adherence to those requirements. Our analysts advised us that we either had bad pilots or bad policy. We believed it was the latter. Our briefings, like so many in the aviation industry (as shown in the LOSA archive), had become so overloaded and were so often conducted by rote that many crews were either choosing not to adhere to the seemingly irrelevant policy or they dutifully followed it, only to find out later, through debriefing, that what they spent so much time briefing wasn’t focused on or directed toward what they should have been briefing.

Briefing Better

It is time to rethink the way we brief — not only to address these issues but also to create a methodology that incorporates recent breakthroughs in cognitive theory regarding decision making in the very environments that are proving to be so challenging for pilots. After a year of research and development, we came up with four goals for our briefings:

- Threat forward. Following the law of primacy (that information presented first is better retained), crew departure and arrival briefings should first address the relevant threats to the flight and go on to discuss specific countermeasures that could be employed should any of those threats degrade safety margins. An additional benefit of a threat-forward briefing is that in identifying relevant threats early in the briefing, those threats tend to positively inform the subsequent departure or arrival plan.

- Interactive. The briefing design should encourage interaction between the PF and PM. It is time to put away the age-old notion of “my leg, your leg.” The desired goal should be an “our leg” mindset where the PM plays a leadership role in developing critical content of the briefing. After all, industry accident data continue to reveal that it is the PM who will play a significant role in noticing and re-establishing safety margins should they deteriorate.

- Scalable. Just as no two departures or arrivals are the same, neither should be the briefings that precede them. Yet on today’s modern flight decks, crews are required to go through the same litany of items for each flight leg. Crew briefings need to be scalable. Professional aviators know how to discern what is important based on proficiency, familiarity, flight complexity and a host of other factors that may or may not be relevant at the time

- Cognitive. Finally, following the principle of recency (that information presented last also is well retained), crew departure and arrival briefings should conclude with a recap of the critical threats and associated countermeasures, as well as specific PM duties for each particular departure or arrival. Why is this so important? Cognitive psychologist Gary Klein, Ph.D., a leading researcher in recognition-primed decision-making theory, has determined that professions requiring rapid decision making in high workload environments subject to rapidly changing conditions (i.e., fire-fighting, law enforcement, the military and aviation), will involve decisions based on recognition-primed pattern-matching. A pattern-match, according to Klein, is an action that is derived from relevant cues, expectancies and goals. These cues, expectations and goals normally will be a result of insights and expertise gained through specific training or routines, professional study, deliberate practice, or overall experience. In very rare cases such as Capt. Chesley Sullenberger’s “miracle on the Hudson,” (US Airways Flight 1549) experts will seek a pattern-match that is “close enough” because the situation is unfamiliar to them, requiring some level of improvisation. In any case, a successful outcome will require an appropriate pattern-match. For this reason, flight crews should brief in a manner that will serve to prime them with potential pattern-matches. Once these pattern-matches and the cues that should elicit them have been mentally primed, it is a lot more likely that when an abnormal situation arises, the crew will be able to trigger these pattern-match–based responses quickly and accurately.

Set-Up and Brief (T-P-C)

In order to incorporate these four goals, we came up with a better way for crews to prepare for departures and arrivals. First, they perform a set-up. The set-up is a very specific, deliberate process in which both the PF and PM take time, normally without discussion, to ensure all required and applicable items are ready to go. These include a review of the weather, applicable notices to airmen, set-up of their electronic flight bags, instrument panels, navigational guidance and appropriate crosschecks [e.g., automatically uploaded departure or arrival waypoints in the flight management computer). The reason for a “silent” set-up is that we only want crews actually discussing relevant items that may affect safety. We found no data to support the fact that a verbal crew crosscheck of automatically loaded systems is necessary. Though that might have been important when a system was first introduced, after many years of improvement and proven reliability, a verbal review is no longer needed. Knowing what we now know about the importance of priming and pattern-matching, we are convinced that every word crews speak during a briefing is critical and potentially life-savtocing.

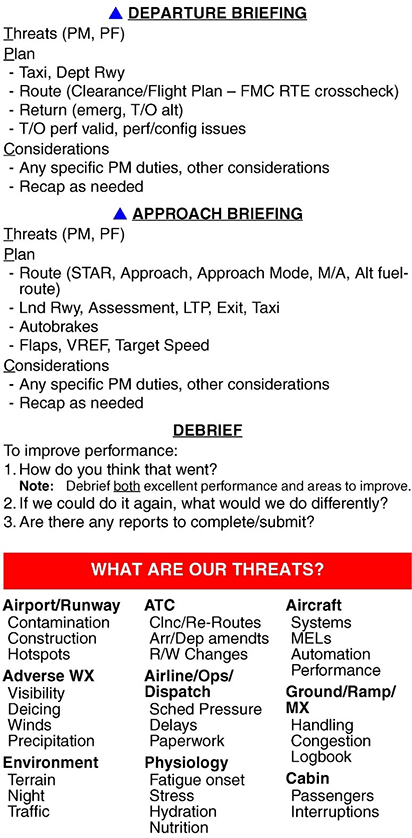

Once both crewmembers are set up, the newly devised “T-P-C” (threats-plan-considerations) briefing begins with the PF asking the PM to review any relevant threats that might be anticipated. By requiring the PM to begin the discussion in this manner, a level of ownership and interactive engagement is fostered. The PM must take time to prepare an answer to the inevitable question that will start the briefing: What are our threats? The crew will then discuss and decide on countermeasures for each relevant threat identified. We provide our crews with a quick reference card that includes a summary of the briefing format, a tool for conducting debriefs, and a list of common threats as a memory jogger. On complex, high-risk departures and arrivals, the threat portion of the briefing can be the most significant and lengthy component of the overall discussion.

Next comes the PF’s plan. There was considerable debate over what should be included in the plan, as we did not want to revert to the long, drawn out list of the required items that we were trying to revise. (This is an exercise each respective airline will have to perform in the process of deciding what guidance to include.) Like briefing threats, however, the plan portion should be relevance-based, and scaled up or scaled down appropriately. If a crew is about to perform its 10th arrival and visual approach in the same sunny conditions to an airport to which they have been flying all month, then the discussion will normally be appropriately scaled down due to high proficiency, familiarity and low risk. If, on the other hand, there exists low familiarity and high risk, then much more detail is required.

Finally, the considerations portion of the briefing is intended to be a recap or summary of the discussion. It is particularly important if the briefing has been scaled up due to a combination of high risk and complexity. A review of specific PM duties will serve to prime the PF and PM for action should any relevant threats require the agreed-upon countermeasure(s).

The Rollout

The most frequent questions we are asked are, “How did you get your flight operations leadership to buy off on such a big change to your SOP?” and “How did you go about communicating the change to your pilots?” The answer to the first question is easy: We showed them the voluntary safety data and proposed a solution that was more in line with what crews were actually doing and one that incorporated human factors science. Regarding the second question, we spent considerable effort communicating the need for a change several months in advance. We then developed a robust training module, including video examples and, more importantly, emphasizing the why behind the change. On the day of the rollout, numerous flight operations leaders were available at each domicile to ensure a smooth transition and answer any lingering questions. Several months after the rollout, we conducted a fleet-wide survey to obtain feedback on how well the change was being incorporated and to learn how it could have been better trained and implemented. The entire process received an 84 percent approval rating.

Autonomy, Mastery and Purpose

It is time to unshackle our line crews from the decades-old required list of briefing items. As Dan Pink said in his New York Times bestseller, Drive — The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us, “Carrots and sticks are so last century. For 21st-century work, we need to upgrade to autonomy, mastery and purpose.” The brief-this-or-else stick places the motivation in the wrong place. We need to allow crews the autonomy to scale and tailor their briefings according to the specific situation at hand, not require a one-size-fits-all solution. We must further encourage crews through revised SOPs to exercise their professional mastery in analyzing risk and crafting management strategies to mitigate relevant threats to the safety of flight and to develop appropriate plans of action based on conditions. The purpose of briefing is also the purpose of a professional pilot: to maximize safety. The Birmingham crew thought they were briefing in the safest possible manner, but despite their compliance with all the rules, it just wasn’t enough. We can and we must do better.

Capt. Rich Loudon is an instructor evaluator and leads the Human Factors Working Group for Alaska Airlines. richard.loudon@alaskaair.com

Capt. David Moriarty is the author of Practical Human Factors for Pilots and a member of the Royal Aeronautical Society’s Human Factors Group.

A version of this article was first published in Aerospace, the magazine of the Royal Aeronautical Society.

Featured image: artisticco | iStockphoto

UPS accident: U.S. National Transportation Safety Board