This article is intended to provide a picture of the civil aviation industry in Taiwan and to describe the Civil Aeronautics Administration’s (CAA’s) efforts to enhance flight safety, including the development and implementation of a state safety program (SSP), service provider–implemented safety management systems (SMS), voluntary and mandatory reporting systems, more stringent operational regulations for aging aircraft, and improved oversight programs. This article also briefly describes the actions taken by the CAA to cope with the threats of runway safety, controlled flight into terrain (CFIT) and loss of control–in flight (LOC-I). Finally, this essay ends with a look at future prospects for Taiwan’s aviation safety.

Global Picture

The Taipei Flight Information Region (FIR), managed by the CAA, accommodates 18 international routes and four domestic routes. In 2017, the Taipei FIR provided over 1.66 million instances of air traffic control services and handled over 65.98 million passengers, including both inbound and outbound flights. From January through July 2018, over 1.01 million instances of air traffic control services were provided in the Taipei FIR, with over 40.17 million incoming and outgoing passengers.

By end of 2018, Taiwan’s civil aviation industry comprised eight civil air transport operators and nine general aviation (GA) operators with a total of 275 airworthy civilian aircraft. Figures 1 and 2 show the growth in operators and aircraft since 1996.

Currently, China Airlines and EVA Airways are Taiwan’s two largest airlines. In 2017, China Airlines ranked 27th in the word in international passenger volume and seventh in international cargo volume. EVA ranked 37th, and 17th, respectively. In addition, there are 11 certified domestic aircraft repair and maintenance companies, two flight training institutes and three aircraft maintenance training institutes in Taiwan. By the end of 2018, there were 3,135 certified pilots and 2,190 maintenance engineers.

Figure 1 — Numbers of Aircraft Operators in Taiwan, 1996–2018

GA = general aviation

Source: Civil Aeronautics Administration, Tawain

Figure 2 — Numbers of Taiwan-Registered Aircraft, 1996–2018

Source: Civil Aeronautics Administration, Tawain

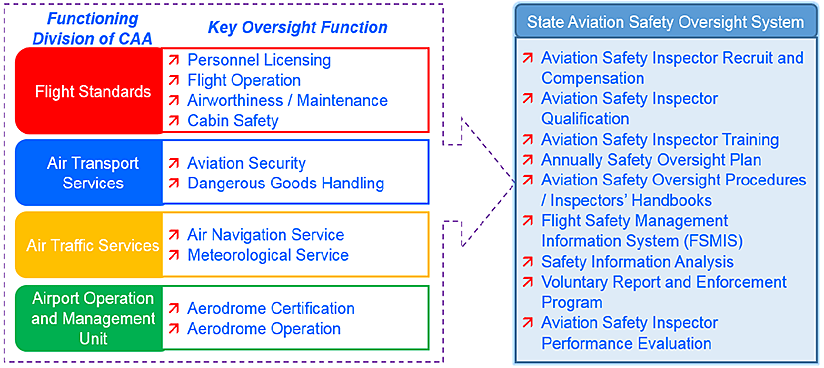

Safety Oversight

According to Taiwan’s Civil Aviation Act, CAA is responsible for ensuring aviation safety in Taiwan. CAA has had an established aviation safety oversight system since the 1950s. In 1996, CAA introduced the aviation safety inspection system to cope with fast-growing air transportation in East Asia. This inspection system is based on the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration’s (FAA’s) surveillance system. CAA’s oversight functions and responsibilities were reassessed and redefined. Accordingly, additional aviation safety inspectors were recruited to ensure regulatory compliance in flight operations, initial and continued airworthiness, cabin safety, handling dangerous goods and aviation security. Figure 3 depicts CAA’s safety oversight system and the key oversight functions of the CAA divisions.

Figure 3 — CAA’s Key Oversight Functions and Safety Oversight System

Source: Civil Aeronautics Administration, Tawain

The CAA works to continuously improve safety oversight by following the guidance contained in the International Civil Aviation Organization’s (ICAO’s) Safety Oversight Manual (Doc. 9734). CAA also is rewriting its SSP to incorporate as much as possible the requirements of the second edition of ICAO Annex 19, Safety Management.

To continue to enhance aviation safety, CAA revises its safety oversight to keep pace with current international standards. For example, because of the expected growth in air transportation in the foreseeable future, CAA is committed to transitioning its safety management approach from the traditional compliance-based oversight to risk- and performance-based oversight. As a result, CAA has asked aircraft operators to introduce safety performance indicators (SPIs) that are relevant to ICAO’s the top three identified risks — controlled flight into terrain (CFIT), runway safety–related events and loss of control – inflight (LOC-I) — as part of their SMS SPIs. Operators also must monitor their fleet performance through flight operational quality assurance (FOQA) and reliability control programs.

Safety Performance

In the past two decades, Taiwan’s aviation safety has improved, as evidenced by declining accident rates.

Figure 4 shows the five-year moving average of the Taiwan fleet’s hull loss accident rate. Figure 5 illustrates the 10-year moving-average for the serious incident rate of the airlines. Over the last decade, since CAA has sought to implement a systematic approach to oversight and tried to harmonize regulations according to prevailing ICAO standards and recommended practices (SARPs), Taiwan has reached a high level of flight safety in turbojet aircraft operations.

Figure 4 — Five-Year Moving Average of Taiwan’s Hull Loss Accident Rates, 1997–2018

Source: Civil Aeronautics Administration, Tawain

Figure 5 — Ten-Year Moving Average of Taiwan’s Serious Incident Rates, 2008–2018

Source: Civil Aeronautics Administration, Tawain

Taiwan suffered two fatal ATR 72 accidents within eight months in 2014 and 2015. On July 23, 2014, TransAsia Airways Flight GE222 crashed on approach to Magong Airport (now Penghu Airport) on a scheduled domestic flight. Forty-eight of the 58 people on board were killed. On Feb. 4, 2015, TransAsia Flight GE235 crashed shortly after takeoff from Taipei Songshan Airport. Forty-three of the 58 passengers and crew were killed.

The GE222 accident investigation report published by Taiwan’s Aviation Safety Council (ASC), said, “The noncompliance with standard operating procedures breached the obstacle clearances of the published procedure, bypassed the safety criteria and risk controls considered in the design of the published procedures, and increased the risk of a controlled flight into terrain (CFIT) event.”

The ASC’s investigation report for GE235 states, “Flight crew coordination, communication, and threat and error management were less than effective, and compromised the safety of the flight. Both operating crewmembers failed to obtain relevant data from each other regarding the status of both engines at different points in the occurrence sequence. The pilot flying did not appropriately respond to or integrate input from the pilot monitoring.”

As the investigations into these two accidents proceeded, the CAA reviewed its technique for auditing flight crew discipline. As a result, CAA has undertaken a series of actions to improve its oversight system, especially on the surveillance of flight operations. Specifically, more attention and manpower were allocated to facilitate the implementation of SMS by airlines.

Implementation of SMS

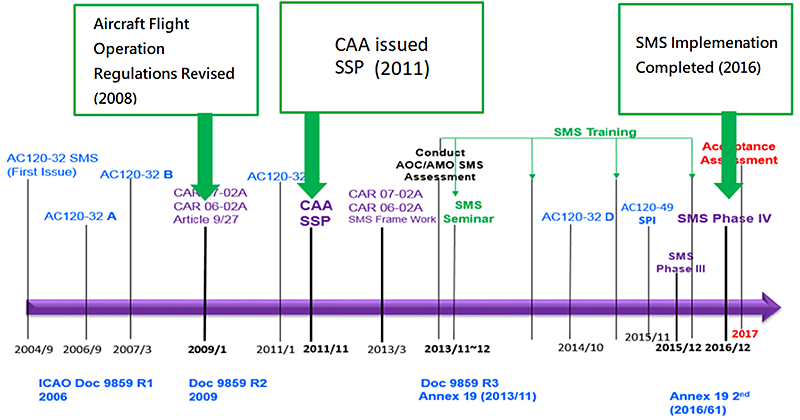

Despite the cessation of its ICAO membership in the 1970s, Taiwan is still committed to doing its best to comply with ICAO SARPs. To this end, the CAA stays abreast of current regulatory developments regarding aviation safety. In addition, the CAA also keeps track of likely future developments. Because it tracked information over the years about SMS-related developments, the CAA issued guidance material in 2004 to introduce the SMS concept and provide guidance to the airlines for establishing SMS. This action was taken before the release of the first edition of the ICAO Safety Management Manual (Doc. 9859) in 2006.

Following ICAO’s mandate for setting up SMS in 2007, the CAA amended its civil aviation regulations in 2008 to require domestic airlines, repair stations, airports and training organizations to establish SMS according to the ICAO SMS framework. Industry stakeholders were required to have their SMS implementations completed by the end of 2016.

As shown in Figure 6, Taiwan’s SSP was first published in 2011 and has been consistently revised in accordance with the most recent ICAO standards. The current Taiwan SSP version (V3.4) was released in December 2018.

Figure 6 — Timeline of SMS Implementation in Taiwan

Source: Civil Aeronautics Administration, Tawain

History of SMS Implementation

In 2008, CAA amended its aircraft flight operation regulations (AOR) to mandate that civil transport operators establish and implement SMS programs acceptable to CAA. At a minimum, an SMS must be able to Identify safety hazards, ensure that remedial action is implemented, provide continuous monitoring and regular assessment of the safety level achieved, and provide continuous safety improvement.

An SMS also must clearly define safety accountability throughout the operator’s organization, including assigning the direct managerial level for safety. The SMS should provide a clear description of the methodology for complying with the SMS implementation framework defined in ICAO Doc. 9859.

The revised AOR further requires that an operator operating aircraft with maximum takeoff mass (MTOW) exceeding 27,000 kg (59,524 lb) shall establish and maintain a flight data analysis program that is nonpunitive and contains adequate safeguards to protect the source(s) of the data.

The updated AOR also set up a requirement for GA operators flying large transport category airplanes to establish and implement an SMS with the same functions and implementation framework.

Repair station operators were required to establish and implement an SMS within the same time frame, but organizations responsible for the type design/manufacture of aircraft were given until November 2013 to begin the process.

Development of SMS Guidance Material

To promote understanding of SMS and to help service providers to establish and implement effective programs, the CAA reviewed SMS guidance material/tools developed by ICAO, other regulatory authorities and the Safety Management International Collaboration Group (SM ICG). The CAA has released a variety of guidance materials, including the following:

- Advisory Circular (AC) 120-032D, “Safety Management System” — This AC provides guidance on establishing and implementing an SMS, including guidelines for conducting a gap analysis (between SMS requirements and the existing quality management and/or other management systems), as well as the phased implementation of the SMS.

- AC 120-049, “Safety Performance indicators” — This AC is issued to provide general guidance and principles on the development of SPIs for air operator’s certificate (AOC) holders and repair station certificate holders.

- “The Senior Manager’s Role in SMS” — CAA translates the SM ICG booklet, which provides practical guidance to help senior managers of each service provider to understand the essence of leadership, accountabilities and legal responsibilities with respect to SMS. It is provided to the newly appointed general managers when they formally assume office.

- “10 Things You Should Know About SMS” — CAA translates the SM ICG brochure to help general aviation employees to understand what SMS is and how it relates to their work.

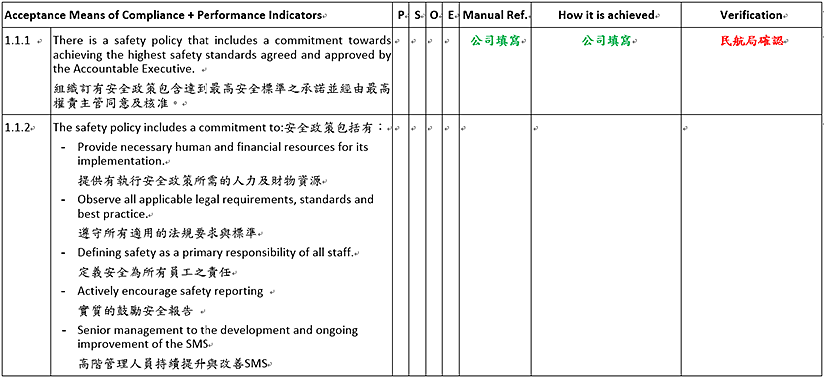

Development of Standard SMS Evaluation Tools

The CAA, working with airline specialists, developed an SMS assessment tool based on SM ICG documents to ensure the programs comply with regulatory requirements and prevailing international standards. The tool provides a comprehensive checklist for evaluation of compliance status and effectiveness of an SMS. This checklist includes questions and evaluation criteria associated with individual SMS elements. In total, there are 178 questions, including 111 questions for ascertaining compliance status with the minimum standards. The other 77 questions pertain to best practices. This checklist is in Chinese and English to aid comprehension and serves as CAA’s standard tool to evaluate the SMS established and implemented by each service provider.

Figure 7 — Sample Checklist of CAA’s SMS Evaluation Tool

Source: Civil Aeronautics Administration, Tawain

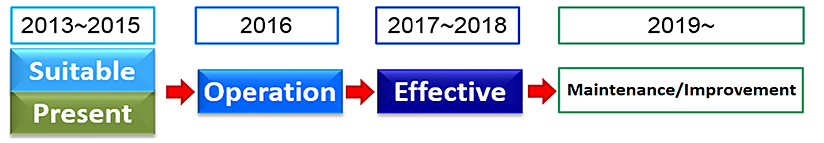

For most organizations, it takes time to implement an SMS and advance to the fully effective level. Therefore, CAA has designated the time frame for airlines and repair stations, as shown in Figure 8, to implement and improve their SMS.

Figure 8 — SMS Time Frame for Airlines and Repair Stations

Source: Civil Aeronautics Administration, Tawain

CAA begin offering SMS training courses in 2014. The courses, based on standardized ICAO SMS training material, were developed with input from airline senior managers and emphasize effective SMS implementation, with examples. Instructors are drawn from airlines and the CAA. Currently, about 600 people have participated in CAA’s SMS training.

Implementation phase- exertion of SMS assessments

In 2012, CAA began using an audit program to evaluate the adequacy and efficiency of the SMS programs developed by local airlines and repair stations. The depth and frequency of the evaluations were calibrated to take into account the progress each SMS has achieved. From 2012 through 2017, five major airlines and two repair stations were surveyed and found satisfactory. Since 2018, CAA’s major effort has been to ensure that their SMS system operated with adequate quality. Fatigue management by air transport operators also will be emphasized.

Further Actions to Enhance Aviation Safety

CAA has developed two compulsory reporting systems and a voluntary system, in accordance with relevant ICAO requirements. One of the compulsory reporting systems covers flight safety events and defines the events that operators are required to report to the CAA for investigation. Also. compulsory is a service difficulty reporting system that defines which serious failure, malfunction or defect of an aircraft, airframe engine, propeller, appliance or component must be reported for the purpose of analysis, correction or issuance of airworthiness directives.

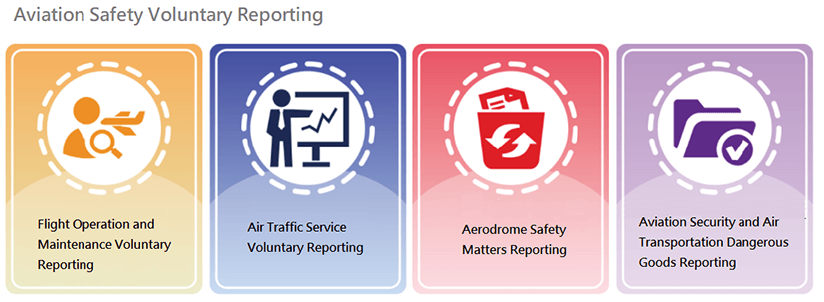

The voluntary reporting system is intended to proactively identify potential hazards through collecting, analyzing and investigating operational data, through which CAA can take all necessary actions to prevent flight safety events from occurring. Four areas are included in the reporting system: flight operation and maintenance, air traffic service, aerodrome safety matters, and aviation security and air transportation of dangerous goods (Figure 9).

The aviation safety voluntary reporting system is a nonpunitive and confidential reporting system. All personal information will be de-identified after processing according to the Personal Information Protection Act.

Figure 9 — Categorization of CAA’s Aviation Safety Voluntary Reporting System

Source: Civil Aeronautics Administration, Tawain

Improvement Efforts

As the international aviation community has done, CAA has identified runway safety, CFIT and LOC-I as the top three risks. As a result, a number of actions have been taken.

First, to emphasize and to mitigate the risk of runway safety–related events, CAA organized two relevant symposiums in 2012. Based on the consensus of these symposium and incident investigation reports, aircraft operators were required by CAA to review and take action to improve the following five aspects:

-

- Company policies;

- SMS implementation;

- Flight crew training;

- Mission dispatch; and,

- Standardization in operation procedures and technical skills.

In addition to supervision of the efforts undertaken by aircraft operators in these regards, in 2014, CAA convened another safety meeting. In this meeting, besides reiterating the 2012 consensus, CAA also established new approach and landing standards to enhance safety.

In 2016, CAA further required the airlines to establish a risk-control plan to deal with runway safety–related events, CFIT and LOC-I. The following year, CAA requested the airlines to extend the scope of their risk-control plan to introduce monitoring, analysis of the relevant FOQA parameters and, depending upon the result, to take adequate rectification if deemed necessary.

Following the two TransAsia (TNA) accidents, the CAA took the several remedial actions. First, it immediately conducted an in-depth inspection to re-check TNA’s compliance with both ICAO standards and Taiwan aviation regulations. Second, CAA increased the frequency of cockpit en route inspection on TNA’s fleet and the number of on-site inspections. CAA also established another action plan for safety oversight. This new oversight plan is composed of three sequential segments — immediate, short-term and mid-term actions. This plan applies not only to the TNA fleet but also to all other national air operators. They were required to fully implement SMS by the end of 2016 and thereafter to submit their SPIs, safety performance targets and safety action plans to the in-charge principal operations inspector/principal maintenance inspector for acceptance each year before the end of January.

Legislations on Management of Aging Aircraft

Civil aircraft are designed to remain airworthy, provided proper operation and maintenance programs are followed. Nevertheless, engine performance will be degraded as time passes, and aircraft downtime will be longer due to spare parts supply difficulties. Operation and maintenance costs will also grow dramatically. As a consequence, the number of abnormal occurrences will inevitably increase for aging aircraft, and operators must develop more intensive and dedicated maintenance programs for ensuring safe operation of their aging fleets. CAA, as the regulator, has moved to enhance surveillance of aging airplanes in two ways: developing regulations and conducting dedicated compliance inspections to ensure safety of the aging fleets.

First, CAA adopted U.S. Federal Aviation Regulations (FARs) Part 121.368, which was later re-designated as Part 121.1105 “Aging Airplane Inspections and Records Reviews,” and amended the operation regulations the same year aging airplane requirements was introduced into FAR. Current regulations require that each airplane used for civil transportation shall undergo its first aging inspection and records review within five years of the start of its 15th year in service; thereafter, aging inspections and records reviews are to be conducted at intervals of no greater than every seven years.

CAA has attempted, through legislation, to ensure that Taiwan’s aviation regulations are in line with those of other countries regarding the management of aging aircraft. Additional aging airplane rules have come into effect, including rules dealing with damage tolerance inspections on fatigue critical structures, widespread fatigue damage and limits of validity (LOV), fuel tank safety, and electrical wiring interconnection systems. Moreover, CAA also forms one specific task team to conduct special audit program for aging airplane. CAA’s vision is, not only to ensure the compliance effectiveness among the domestic and international operators, but also to establish the standardized measures of compliance as necessary.

Since aging aircraft will soon face the LOV, the affected operators must incorporate mandatory inspections and structural modifications or introduce new aircraft to eliminate the aging aircraft maintenance workloads.

Restricted Use of Aging Aircraft

Currently one Taiwanese airline operates with eight McDonnell Douglas MD-82/83 airplanes, ranging in age from 21 to 28 years. Because of their age, the condition of these airplanes — including engine performance — has declined and the number of events and flight delays due to airplane system failures has increased. In addition, spare parts have become more difficult to obtain, causing longer maintenance times.

CAA decided to set a total monthly flight time limit for this fleet. Beginning in March 2017, the total monthly flight time of this MD-82/83 fleet was restricted to 1,300 hours to allow more time for inspections and related maintenance tasks. This flight time restriction now is reviewed monthly. If the performance of the fleet improves, the limit is loosened; otherwise, the limit remains unchanged or becomes more stringent. For example, in May and June 2017, the limit was raised to 1,470 hours but adjusted back to 1,350 hours the following month due to an increase in the number of abnormal events.

In addition to the age restrictions, in October 2018, CAA further mandated that after Jan. 1, 2020, a civil air transport operator shall not operate passenger airplanes older than 26 years.

Fatigue Management

To further enhance aviation safety, CAA has recognized that fatigue risk must be managed by both CAA and the operators. CAA has required the airlines to comply with the flight crew flight time limitations prescribed in Aircraft Flight Operation Regulations. These regulations were amended in 2013 to mandate flight duty time limits for cabin crew. In addition to the daily inspections, CAA inspectors also monitor the trends of flight duty scheduling. This can be done by reviewing the records of flight and cabin crew flight time. To optimize crew scheduling, CAA encourages the airlines to use computerized programs for implementation of the fatigue risk management system (FRMS). Along with this, the FRMS rulemaking is currently in progress.

Safety Prospects

Although Taiwan’s safety performance is continually improving, there is still work to be done. CAA will continue its surveillance of SMS operations within the Taiwan air transport industry to ensure flight is as safe as possible.

In addition, new targets have been defined. First, as specified in ICAO Annex 19 (2nd edition) and ICAO’s Global Aviation Safety Plan, CAA will revise the SSP and plans to transition from traditional compliance-based oversight to risk- and performance-based oversight by the end of 2022.

CAA also will consider the feasibility of instituting the Civil Aviation Data Center (CADC) for big data collection and sharing. In fact, the CADC is expected to serve as the counterpart of the European Aviation Safety Agency’s Data4Safety (Partnership for Data Driven Aviation Safety). Through data analysis, CADC will be able to identify the high-risk factors, to locate priority topics for safety surveillance and to formulate possible mitigation measures.

Featured image: © CreativeBringer | VectorStock