The U.S. government’s coming wave of security measures for small unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) has the potential to disrupt or delay regulatory changes that would expand UAS operators’ basic capabilities, several experts told the FAA UAS Symposium in March. Some called security vital to the integration of UAS aircraft in the National Airspace System (NAS). The symposium was cosponsored by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and the Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International (AUVSI).

FAA Acting Administrator Dan Elwell described safety and security as inseparable. “The next 12 to 18 months are critically important to UAS integration. We’re working to expand small-UAS operating parameters while making sure we appropriately consider security and privacy issues,” he said. “We need to mitigate risks to national security and public safety posed by people who aren’t playing by the rules, whether by intent or ignorance. One malicious act could put a hard stop to all the good work we’ve done on drone integration.”

National aviation policy requires emphasis on remote identification (ID) and tracking for UAS, Elwell said. “We’re committed to moving very quickly to establish remote ID requirements. If you want to fly in the system, you have to be identifiable — and you have to follow the rules,” he said.

Operators of small UAS aircraft who have come to FAA’s attention for jeopardizing NAS operations often have been called “the clueless, the careless and the criminals,” another FAA official said. Angela Stubblefield, deputy associate administrator, FAA Security and Hazardous Materials Safety Organization, said, “We need to move forward with a robust security framework. Anonymous operations in the NAS are antithetical to safety and security.”

Federal government departments are responding to presidential directives, said Michael Kratsios, deputy assistant to the president and deputy U.S. technology officer, Executive Office of the President. The directives’ three-year UAS Airspace Integration Pilot Program will help to advance this aviation industry segment with security in mind, he said.

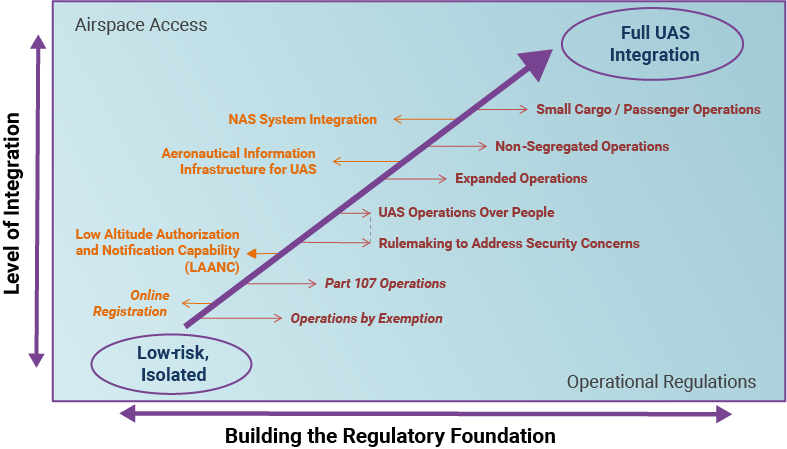

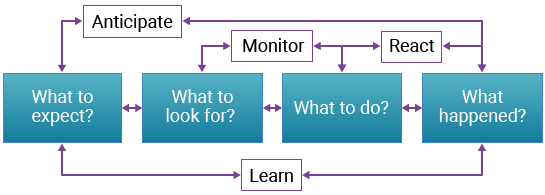

The Path to Full Integration

Source: U.S. Federal Aviation Administration UAS Symposium

“We need to figure out a way to safely enable beyond visual line of sight operations, nighttime operations and flight over people operations,” Kratsios said. “But the potential misuse or errant use of this technology poses unique safety and security challenges. The federal government today has limited authority to deploy technology to detect and defeat UAS-based threats. The administration [of President Donald Trump also] is working on a legislative proposal to enable certain agencies to use technology capable of detecting and, if necessary, mitigating UAS-based threats to certain sensitive facilities and assets.”

This security-infused view of safety has influenced AUVSI to collaborate closely with FAA on finding balanced solutions, said Brian Wynne, president and CEO of the association.

The next regulatory step to enable routine UAS flight over people, for example, has been delayed for more than a year, Wynne said. Companies, therefore, stepped up with proposals. “AUVSI has long supported a registration system for commercial and recreational UAS operators, which is a prerequisite for remote-identification solutions,” he said.

“Maintaining federal sovereignty of the airspace keeps our skies safe and helps foster innovation. We believe that a UAS registration system promotes responsibility by all users of the NAS and helps create a culture of safety that deters careless and reckless behavior. We need broader engagement from our government partners — notably those responsible for national security — to understand their specific current concerns and to work collaboratively to address them.”

The federal government’s last two years of work on defenses against security threats from small UAS aircraft focused on changing laws and on technical research. Brendan Groves, counsel to the deputy attorney general, Department of Justice, said, “We have watched with growing alarm as ISIS [the militant group also known as the Islamic State] perfects the art of transforming commercially available drones … into weapons of war.”

UAS Risk Mitigation

Over the past 12 months, FAA has focused on educating staff and non-staff stakeholders about the safety roles of the UAS pilot, airworthiness standards, operating limitations and segregated airspace. Training covers safety analysis of drones and UAS operations, safety-assurance processes for aircraft certification and operations, and safety expectations from risk-based decision making.

Safety management system principles — common for airline operations, air traffic control (ATC) and airport operations — often apply to UAS with no need for reinvention, said Wes Ryan, unmanned aircraft certification lead, FAA Flight Standards Service.

FAA’s performance-based approach — the preferred alternative to past prescriptive requirements and mostly quantitative targets — applies proactive and predictive approaches, Ryan said. “We’re trying to remove ourselves from some of the detail work for low-risk types of UAS operations. So you’ll see FAA moving toward industry-based compliance processes,” he said.

FAA’s Elwell noted that one crucial step toward UAS traffic management — low-altitude authorization and notification capability (LAANC) — is poised to offer immediate safety benefits and compatibility with the security initiatives. LAANC automates how UAS operators get permission from ATC to fly in predetermined areas of controlled airspace, enabling “controllers to mitigate risk by ensuring that no other aircraft are operating near the drone,” he said. FAA began nationwide beta testing April 30. “Nearly 300 ATC facilities and 500 airports will be covered by September,” Elwell said.

LAANC services will help to segregate most drones from manned aircraft with minimal ATC involvement. Tim Arel, deputy chief operating officer, FAA Air Traffic Organization, said, “Relinquishing lower altitudes — [to keep drones] away from the flows of normal aircraft operations — is something new, but something certainly achievable. ATC now can share safety information in real time” with the manned-aircraft pilots operating at those altitudes.

Air Traffic Risks

Government-industry panels convened by FAA recently analyzed “credible” — not merely “possible” — air traffic–attributed risk in UAS integration, said Maggie Geraghty, manager, Safety Management Group, FAA Air Traffic Organization. Panels studied effects in every class of airspace; ATC policy, requirements and airspace authorizations; impacts of a new UAS mission or changes to UAS operation; the role of pilots; and how all aircraft and ATC equipment are affected.

“We cannot accept a high-risk hazard into the ATC system unless the initial risk of a UAS is mitigated down to an acceptable medium level or low level. We look for feasible risk mitigations,” Geraghty said. “A feasible risk mitigation might be procedure-based, training-based or awareness-based.”

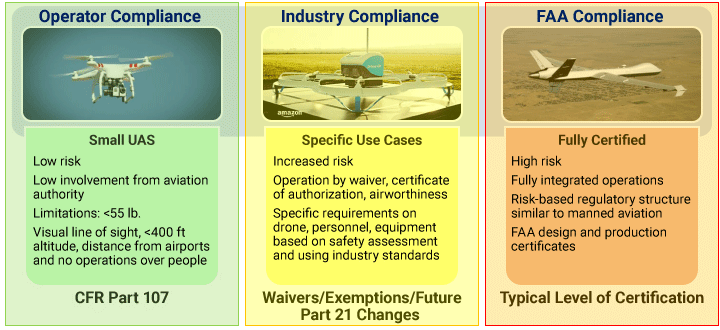

FAA’s latest regulatory-structure model has three classes of UAS-certification standards: low-risk flight operations under Federal Aviation Regulations Part 107, Small Unmanned Aircraft Systems; high-risk flight operations that require full type certification of aircraft and operations by the agency; and middle-risk flight operations that will rely on industry-developed aircraft certification standards and industry-based operator-compliance processes, FAA’s Ryan said.

Risk-Based FAA Direct Involvement

Source: U.S. Federal Aviation Administration UAS Symposium

Resilience engineering plays a significant role. He said, “It makes sure that you’ve thought through whether or not the human and the system interact to respond to failures in a safe manner.”

The model’s classes are consistent with the Specific Operational Risk Assessment (SORA) process advocated by Lorenzo Murzilli, manager, innovation and advanced technologies, Federal Office of Civil Aviation of Switzerland.

Murzilli told the symposium that subjectivity and variation in UAS risk assessments among nations can be overcome by standardization. In Europe, a working group of the Joint Authorities for Rulemaking of Unmanned Systems (JARUS) expects to issue recommendations for public comment in mid-2018 that will follow up its first report from July 2017.

Resilience Engineering

Source: U.S. Federal Aviation Administration UAS Symposium

UAS Aircraft Detection

FAA’s Stubblefield briefed the symposium on drone-detection and tracking research. In 2016, FAA and the Department of Homeland Security began a pilot project studying the use of detection technologies in the airport environment, she said, focusing on how small UAS interact with ATC.

In 2017, some federal departments received their first legal authority to detect drones and to counteract defined types of drone flights, Stubblefield said. The Department of Justice and members of Congress also began to propose related laws to protect and to defend facilities and personnel designated as critical infrastructure, she said.

Groves, from the Department of Justice, explained the legacy legal impediments. “If you try to use technologies that are capable of detecting and, if necessary, disrupting unmanned aircraft, you immediately confront a thicket of federal laws that simply haven’t kept pace with the times. The level of uncertainty we face now — even in the federal government — is untenable,” he said.1,2

Anh Duong, FAA’s deputy associate administrator for security and hazardous materials safety, emphasized that “detecting, tracking, mitigating or countering a nefarious UAS” requires safety and security stakeholders to understand the legal issues and limitations placed on technological solutions. Unlike military countermeasures, “A lot of them have not been evaluated in homeland-security settings,” she said.

Contentious ID Issues

Symposium organizers called drone ID and tracking “the hot topic” of the FAA UAS Symposium. Although FAA made no announcements about related rulemaking, Josh Holtzman, director, Office of National Security and Incident Response, FAA Office of Security and Hazardous Materials Safety, outlined work by FAA’s Unmanned Aircraft Systems Identification and Tracking Aviation Rulemaking Committee (ARC), created in June 2017.

FAA plans to use the ARC’s December 2017 report in developing a proposed rule. He said a new FAA ARC in mid-2018 will define in detail the need for remote ID and tracking standards for small UAS and recommend a framework for this rule.

Holtzman said, “Anonymity obfuscates intent.” Current capability to simply detect the UAS radio frequency (RF) used by an intruding operator fails to discriminate among compliant, negligent and nefarious intentions, he added.

Earl Lawrence, executive director, FAA UAS Integration Office, said, “The most contentious thing we talked about during the 2017 ARC was ‘So who has to ID their drones?’” The ARC essentially proposed, “If you’re operating in a location in which operation under Part 107 can be authorized, then that’s the concept of ID systems [applicability],” he said.

Another proposal would require remote ID and tracking for small UAS operators that will be flying from Part 107-limited airspace to airspace higher than those altitude limits or to other controlled airspace. “You would transition to normal ATC systems, such as the automatic dependent surveillance–broadcast [ADS-B Out] transponders that would apply to that group,” he said.

FAA also is considering a “networked and identified” system in which the location of each small UAS aircraft flying at Part 107-defined altitudes and data such as the location of the operator’s control station would be transmitted to FAA’s network for operations.

Implementing any of these approaches would have a ripple effect on many ATC services. Jay Merkle, deputy vice president of the program management office of FAA’s Air Traffic Organization, said, “When we issue an airspace authorization [in the future], we think it’s very feasible and viable — and probably necessary — that we associate the drone ID with that authorization so that everyone in the community can contact the pilot.” The key is having the ability to manage small drones by exception, meaning that controllers normally will not have to talk to drone operators during flight — “distracting controllers from their primary duties,” he said.

Preventing RF interference and related problems is a major priority for drone ID. “We cannot afford to have any small drones operating in areas where we are not providing them services on [cooperative-surveillance frequencies]. We cannot afford to have UAS aircraft transmitting, for example, on a frequency that causes track jumps [from multipath effects] on ATC displays of a final approach to Los Angeles International Airport,” Merkle said.

Another concept for drone ID is the UAS traffic management (UTM) architecture of software applications and databases on a secure network that — like LAANC — interfaces with the UAS industry, said Steve Bradford, FAA’s chief scientist for NextGen. Yet another concept would have ATC obtain UAS operator IDs and aircraft IDs from track-data companies serving designated airspace and airports, he said.

Safely Implementing Defenses

Air traffic controllers’ main security role is safely accommodating local, state and federal law enforcement officers, said FAA’s Arel. ATC manages normal air traffic while responding to security incidents; in-flight, manned-aircraft emergencies; and aircraft rescue and fire fighting operations. FAA’s presentations inferred possible countermeasures such as the use of force, interference with RF and cyber-disruption.

“It’s a delicate balance,” he said. “The security partners let us know what they intend to do. We let them know what the potential impacts are for traffic in the area. Then we work to actively deconflict traffic and ensure a measured response appropriate to the potential threat.”

Several vendors’ products for defending airports against attacks by commercial off-the-shelf drones have been tested. Elizabeth Soltys, UAS security program manager, FAA Office of Security and Hazardous Materials Safety, said the test sites chosen were Atlantic City [New Jersey] International Airport, Denver International Airport and Dallas–Fort Worth International Airport. Normal airline flight operations continued during the two-year pilot project.

The vendors reported 100 percent interception accuracy under conditions in which they knew in advance when researchers would launch “attack drones” during live simulations and the type and characteristics of each drone. Even so, the participants found the tests “arduous,” Soltys said. The tests were not specifically funded, so researchers did not have their preferred analytical metrics, such as independent telemetry data, she said.

Arel also stressed that unsafe responses or overreactions to drone activity by security officials must be kept in check. “Sometimes, the level of risk that the intruder causes is not worth the amount of kinetic energy — or whatever may be deployed — to deal with the issue,” he said. “If someone is operating a drone just 100 ft higher than they should, to the east of an airport in the north-south runway configuration, do we shut down a major international hub for a prolonged period of time to deal with that?”

Notes

- Groves said that the 1984 Aircraft Sabotage Act — which contains “little-known provisions” in Section 32, “Destruction of aircraft or aircraft facilities,” in Title 18 of the United States Code — prohibits willful destruction of an aircraft (now interpreted to include UAS aircraft).

- Groves said the 1968 Wiretap Act as amended in 1986 — notably Chapter 119, “Wire and electronic communications interception and interception of oral communications,” in Title 18 of United States Code — is now interpreted as establishing federal criminal liability for intercepting UAS data links between a ground station and aircraft control systems.

Featured image: © lumyaisweet | VectorStock

Drone technology illustration: © rassco | VectorStock