A study of U.S. fatal helicopter accidents reveals that more than half fell into one of three categories — loss of control–in flight (LOC-I), unintended flight into instrument meteorological conditions (UIMC) and collision during low altitude operations (LALT) while intentionally operating near the surface.1

The U.S. Helicopter Safety Team (USHST) issued a report on its study in October, along with 22 recommended “safety enhancements” that address four general issues — safety management, competency, LOC, and IMC and visibility — and are intended to reduce the number of fatalities.

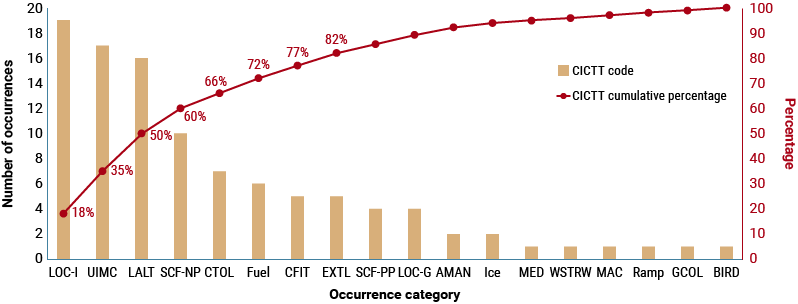

The study examined 104 fatal helicopter accidents that occurred between 2009 and 2013; the accidents were analyzed according to the taxonomy developed by the Commercial Aviation Safety Team (CAST) and the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO). Using the CAST/ICAO Common Taxonomy Team’s (CICTT’s) guidelines, the USHST researchers assigned each accident to a single CICTT occurrence category.

Figure 1 — U.S. Civil Helicopter Fatal Accident Data by CICTT Category, 2009–2013

AMAN = abrupt maneuver; BIRD = bird strike; CICTT = Civil Aviation Safety Team/International Civil Aviation Organization Common Taxonomy Team; CFIT = controlled flight into terrain; CTOL = collision with obstacle(s) during takeoff and landing; EXTL = external load–related occurrence; GCOL = ground collision; LALT = low altitude operations; LOC-G = loss of control–ground; LOC-I = loss of control–in flight; MAC = air prox/airborne collision avoidance system alert/loss of separation/(near) midair collision; MED = medical; SCF-NP = system/component failure or malfunction (non-powerplant); SCF-PP = powerplant failure or malfunction; UIMC = unintended flight into instrument meteorological conditions; WSTRW = wind shear or thunderstorm

Source: United States Helicopter Safety Team

The three most common categories of fatal accidents “accounted for half (52) of the fatal accidents analyzed and were responsible for more fatalities (104) than the remaining CICTT categories combined (96),” the report said.

The USHST, a regional partner to the International Helicopter Safety Team, set a goal in 2016 of reducing the fatal U.S. helicopter accident rate by 2020 to 0.61 fatal accidents per 100,000 flight hours, compared with USHST’s baseline rate of 0.76 per 100,000 hours. That number is the average fatal accident rate for 2009–2010 and 2012–2014 — “the prior five years that have final and reliable data,” the USHST said, adding that the fatal accident rate has been trending downward over the past 15 years, “but it has been below 0.61 only twice, and spiked in 2008 and 2013.”

The USHST goal for 2017 is to reduce the fatal accident rate to 0.69 (or lower) per 100,000 flight hours. Preliminary data for the first six months of the year show a rate of 0.58 per 100,000 hours.

Personal and private flights were involved in more fatal accidents than any other segment of the helicopter industry, followed by helicopter air ambulance operations, commercial operations and aerial application flights. Combined, the four industry segments accounted for 59 percent of the fatal accidents that were included in the analysis. The four were identified as the areas that will be the initial focus of all 22 safety enhancements.

As part of its effort to achieve the goal, the USHST began identifying data-driven risk mitigations that ultimately were announced over several weeks in September and October.

Safety Management

More of USHST’s safety enhancements were aimed at safety management than any other category, addressing pre-flight action, proactive initiatives and beneficial technology. They include the following:

- Developing and promoting recommended practices for preflight inspection, final walk-around and post-flight inspection.

- Providing instructors with recommended practices for a preflight risk assessment of student flights.

- Promoting the installation and use of data recording devices, including video recording, for “detection and monitoring of aircraft and engine limitations that were exceeded; collecting and preserving more data relevant to accident investigation; [and] detecting and correcting procedural noncompliance.”

- Encouraging the development and installation of full-authority idle protection devices “to prevent an unintended loss of engine power” — a recommendation prompted by the May 26, 2010, fatal crash of a Schweizer 269C-1 in Boxborough, Massachusetts.2

Competency

The six safety enhancements addressing competency call for increasing the use of “relevant simulation to rehearse at-risk scenarios to educate and to develop safe decision making.” Among the accidents cited for prompting development of the safety enhancements was an Oct. 4, 2011, accident in which a heavily loaded Bell 206B spun into the East River in New York City, killing two passengers and seriously injuring a third, who died more than a month later.3

Other recommendations dealt with re-defining effective safety culture in a way that is “more applicable and relatable to the day-to-day work of frontline helicopter professionals,” improving transition training for pilots transitioning to make and model helicopters with which they previously had little or no experience, and providing guidance on the improvement of competency-based training and assessments.

Loss of Control

The USHST said it would work to implement five safety enhancements related to LOC-I, including convening a team of training experts “to develop consensus on recommended practices for standard training” of helicopter flight instructors on autorotation and emergency handling.

The USHST also called for adopting “progressive approaches” to autorotation training, developing recommendations for improving simulator models for “outside-the-envelope flight conditions” and encouraging development of a stability augmentation system (SAS) or autopilot or both for light helicopters.

Among the accidents that the USHST said prompted the SAS/autopilot safety enhancement was the Oct. 11, 2012, crash of a Robinson R44 II in Blanco, Texas. The U.S. National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) cited as the probable cause “the pilot’s loss of helicopter control as a result of spatial disorientation due to dark night conditions and marginal visual flight rules weather conditions.”4

IMC and Visibility

Four visibility-related safety enhancements call for research and development on enhanced vision systems technologies, including night vision goggles, “to assist in recognizing and preventing unplanned flight into degraded visibility conditions due to weather and to increase safety during planned flight at night”; and for development of training for “recognition of spatial disorientation and recovery to controlled flight.”

Other recommendations involved:

- Development of best practices for training in threat and error management.

- Development of ways for crewmembers to identify increased risk levels during flights. Among the accidents cited as prompting the safety enhancement was the Nov. 10, 2011, crash of a Eurocopter EC130 B4 into a mountain on the Hawaiian island of Molokai, killing the pilot and all four passengers. The NTSB said a contributing factor was “the pilot’s decision to operate into an area surrounded by rising terrain, low and possibly descending cloud bases, rain showers and high wind.5

USHST’s work sprang from its adoption in 2016 of an approach to accident analysis that closely followed efforts by CAST and the General Aviation Joint Steering Committee (GAJSC), which were operating under their own data-driven processes to develop risk-reduction plans. The GAJSC had established, in 2011, a goal of reducing the general aviation fatal accident rate by 2018 to no more than one fatal accident per 100,000 flight hours. CAST, which was established in 1998, is credited with achieving an 83 percent reduction in the commercial aviation fatal accident rate within 10 years.

Notes

- USHST. Helicopter Safety Team (USHST) Report: Helicopter Safety Enhancements. Oct. 3, 2017.

- NTSB. Accident Report No. ERA10FA283. May 26, 2010. The accident killed an FAA check pilot who was conducting a practical examination for a commercial pilot seeking a flight instructor certificate. The commercial pilot was seriously injured. The NTSB said the probable cause was “the FAA inspector’s rapid reduction of power [by abruptly closing the throttle], which resulted in a loss of engine power, and his decision to initiate a turn during the autorotation without sufficient altitude to clear obstacles.”

- NTSB. Accident Report No. ERA12MA005. Oct. 4, 2011. The report said the probable cause of the accident was the pilot’s “failure to anticipate and correct for conditions … conducive to loss of tail rotor effectiveness (LTE), which resulted in LTE and an uncontrolled spin.”

- NTSB. Accident Report No. CEN13FA010. Oct. 11, 2012. The crash killed the pilot and both passengers.

- NTSB. Accident Report No. WPR12MA034. Nov. 10, 2011. The report cited as the probable cause of the accident “the pilot’s failure to maintain clearance from mountainous terrain while operating in marginal weather conditions, which resulted in the impact of the horizontal stabilizer and lower forward portion of the fenestron with ground and/or vegetation and led to the separation of the fenestron and the pilot’s subsequent inability to maintain control.”

Featured image: © jacoblund | iStockphoto

Robinson R44: U.S. National Transportation Safety Board