With the increasing use of drones in humanitarian operations, safety systems must evolve to support both single-aircraft flights and complex, multi-aircraft missions that involve drones and manned aircraft working together, according to a new report by Flight Safety Foundation.

The report prepared for the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and published earlier in June, presents three specific scenarios that were designed to highlight future needs for advanced safety management for unmanned aircraft systems (UAS), as drones are often known. These future safety capabilities are envisioned as automatically taking the needed steps to reduce known risks and to identify emerging risks to airspace safety and to the safety of people and objects on the ground.

“Unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) continue to expand the effectiveness and outreach of humanitarian and public organizations that provide disaster management and first responder services around the globe,” says the report, “Looking to the Future: Safety System Needs for Humanitarian UAS Operations.”

The document continues, “As operations grow, the safety community is looking at ways for safety systems to evolve with respect to scalability, new operations and diverse platforms, as well as increasing the emphasis on proactive safety risk management.”

Three Scenarios

The Foundation worked with UAS and humanitarian communities to develop scenarios to explore how drones would be used in the future and, through a series of workshops, refined the scenarios to explore the safety services that would be used and to identify the likely risks that a future safety system would need to monitor.

The chosen scenarios – involving the humanitarian response after a natural disaster, wildfire-fighting and delivery of medical equipment in an urban area – were selected as representative of the types of operations performed in disaster management and first-responder situations. All three scenarios were set in the United States, but the report notes that they could be applied internationally.

The disaster-response scenario involved the humanitarian drone operations conducted in the aftermath of a hurricane, sometime between 2023 and 2025, with significant infrastructure damage. In this scenario, humanitarian organizations used drones for both visual line of sight (VLOS) and beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS) operations to identify people who needed help, to document damage and to help emergency responders allocate resources. In addition, media organizations submitted requests to operate their drones within the restricted airspace over the area. Because of the many drones in the area, an “air boss” was responsible for coordinating their movements to ensure safety and to prevent potential airspace conflicts.

The wildfire scenario involved an uncontrolled 2025 blaze in a remote part of the coastal mountains of northern California, with numerous manned aircraft engaged in firefighting operations. The local fire department deployed a swarm of off-the-shelf drones for BVLOS flights to monitor the fire and identify areas where firefighting efforts should be focused. Other drones supported firefighter beacon location transmission. An air boss coordinated aircraft movements, including those of piloted aircraft delivering firefighting materials, but all users shared information with each other as well as with other aircraft in the area.

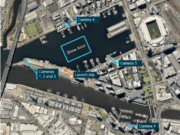

The medical equipment-delivery scenario was set around 2030 in an urban environment that included complex and crowded Class C controlled airspace and explored problems that might arise during a medical mission. In this scenario, a drone was deployed to deliver a defibrillator to a park where there was a medical emergency. During the flight, the drone was rerouted around a helicopter, then lost its connection to the ground station; pre-set fail-safe procedures allowed completion of the flight, with the drone receiving route amendments directly from the UAS traffic management service network to ensure separation from two advanced air mobility vehicles in the area. The connection to the ground station was restored, and the drone successfully completed its mission.

Identifying Risks

Through a series of workshops with experts on humanitarian missions and other subjects, the Foundation identified 14 common risks seen in the three scenarios and recommended monitoring of those risks. The risks included reference altitude calculation errors, ground station loss of power or functionality, separation deterioration (cooperative and non-cooperative), use of out-of-date information and loss of the navigation signal.

Other risks were human pilot loss of situational awareness; loss of command-and-control link, single unit failure; airframe and component failure; physical ground interference; systemwide loss of command and control, ground or air; weather, rapid deterioration or change; out-of-date reference information on terrain and obstacles; physical air interference; and cybersecurity.

After the risks were identified, the next step was “to look at the interactions that occur while planning for and operating a UAS mission,” the report said. “The actions taken and the information that is collected, requested and shared during the course of an incident response can all be monitored to assess and mitigate potential risks.”

The data needs were assessed from a risk perspective and a transaction basis and compared with a data catalog proposed earlier by NASA; this produced an expanded set of information needs with 240 data parameters, including new elements for flight planning such as remote ID identifiers and flight plan routing information, new weather data elements such as microclimate monitoring and new navigational performance indicators such as real-time kinematic GPS. An additional data class involves the use of procedural documents such as checklists and maintenance manuals.

Better Understanding

The report said that the review yielded a better understanding of current and future safety risk management needs for drone flights in humanitarian operations and for other commercial and civil drone operations.

“Strengthening UAS safety is envisioned as a real-time, proactive process that capitalizes on broad information-sharing as part of a just, safety-based approach,” the report said, adding that the analysis is an early step in “planning for the safety systems that will allow these operations to evolve in pace of operations, scope and complexity.”

Image: Kerry Benik, Flight Safety Foundation

This article is based on “Looking to the Future: Safety System Needs for Humanitarian UAS Operations,” a report by Flight Safety Foundation, sponsored by the NASA Aeronautics Research Mission Directorate under Grant No. 80NSSCV20M0248. June 2021.