More data and improved data analysis are key to identifying the causes of runway incursions and developing methods of preventing them, U.S. National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) Member Christopher Hart says.

Hart and other participants in the NTSB’s mid-September forum on runway incursion safety issues emphasized the role that could be played by collecting more relevant data, and analyzing and sharing the data more effectively.

“Perhaps the most challenging issues that warrant better data are the human factors issues regarding human limitations and vulnerabilities, and determining how humans can interact most effectively with rapidly advancing technologies,” Hart said after the forum, which included discussions of concerns faced by pilots, air traffic controllers and airport operators, and also of runway incursion data and trends.

Earlier, he characterized as “good news” the fact that the last fatal runway incursion accident involving a U.S. Federal Aviation Regulations Part 121 air carrier occurred 11 years ago on Aug. 27, 2006, when the crew of Comair Flight 5191, a Bombardier CRJ100ER, attempted to take off from the wrong runway — a shorter runway than the one they had been told to use — at Blue Grass Airport in Lexington, Kentucky. Of the 50 passengers and crew, only the first officer survived.1

However, Hart added, “The bad news … is that despite several interventions, the most severe incursions [Category A and B incursions, which fit the definitions of incidents in which collisions are most likely] … have been on the rise since 2011, after declining for several years.”

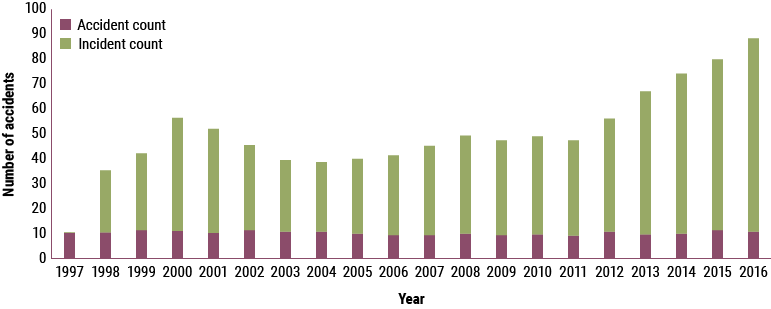

James Fee, the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration’s (FAA’s) Runway Safety Group manager, told the forum that since the FAA began its runway safety program in 1997, the number of accidents involving property damage, injuries and fatalities has remained relatively constant.

Figure 1 shows the number of accidents reported annually over the past 20 years, as well as the number of incidents, which fluctuated until 2011, when the number of reported incidents began to increase.

Figure 1 — U.S. Runway Incursion Accidents and Incidents, 1997–2016

Source: U.S. Federal Aviation Administration

The increase coincided with the 2012 launch of what Fee described as “a very robust runway safety data collection system,” as well as the establishment of voluntary incident reporting programs for air traffic controllers and the strengthening of the safety culture, “where it’s a value to report safety events … so they can be associated with identifying precursors, identifying areas of risk and helping to inform actions that then reduce the … risk in the system.”

Fee said the data show that, since 2011, some 12,857 runway incursions have been reported. In nearly complete data for fiscal 2017 — which began Oct. 1, 2016, and ended less than two weeks after the forum, on Sept. 30, 2017 — runway incursion reports totaled 1,341. Of these, six incursions were placed in the most serious categories as “A and B” events.2

Overall, 66 percent of the 1,341 incursions were classified by the FAA as “pilot deviation,” 17 percent were vehicle/pedestrian incidents, 16 percent were air traffic control (ATC) incidents and 1 percent were “other.”

Of the six Category A and B events, four were considered ATC incidents and two were pilot deviations.

Failure to Hold Short

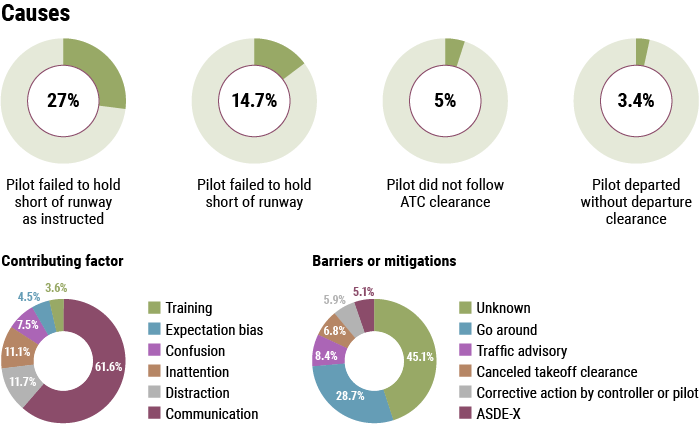

In a separate analysis of data for fiscal 2016, which ended Sept. 30, 2016, the FAA found that 27 percent of the 361 runway incursions that were attributed to pilot deviation resulted from “pilot failed to hold short of runway as instructed” (emphasis added) and 14.7 percent from “pilot failed to hold short of runway” (Figure 2). In 5 percent of the pilot deviations, the pilot failed to comply with an ATC clearance, and in 3.4 percent, the pilot departed without a departure clearance.

Figure 2 — Analysis Summary of 361 Pilot Deviations, Fiscal 2016

ASDE-X = airport surface detection equipment, Model X; ATC = air traffic control

Source: U.S. Federal Aviation Administration

The most frequently cited contributing factor was “communication,” cited in 61.6 percent of reports. When the FAA was able to identify mitigating factors that prevented an incident from escalating into an accident, the most frequently identified mitigation was that the crew conducted a go-around (28.7 percent). More often (45.1 percent), mitigations could not be identified.

In the 74 cases of cases of vehicle/pedestrian deviations, half resulted from the driver entering the runway without ATC authorization, and half involved the driver failing to hold short of the runway, Fee said. Data showed that the most frequent contributing factor was the driver’s confusion and that the most frequently cited mitigation was an ATC instruction to the aircraft.

An analysis of 265 fiscal 2016 operational incidents found that 63 percent were attributed to “ATC cleared aircraft to land/depart on an occupied runway,” and that 19 percent occurred because “ATC did not monitor aircraft position on approach to intersecting runway.” The most frequently cited contributing factor was “distraction by other aircraft” (35 percent), and the most frequently cited mitigating factor was the use of airport surface detection equipment, Model X (ASDE-X), a surveillance system that enables controllers to track surface movement by aircraft and vehicles using radar, satellite technology and multilateration — determining aircraft position using time difference of arrival of transponder signals at multiple antenna sites — (40 percent).

ASRS Analysis

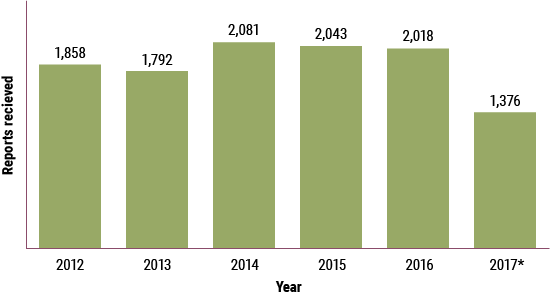

Capt. Gary Brauch, expert analyst for the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration Aviation Safety Reporting Service (ASRS), said his office received 11,168 reports of runway incursions from Jan. 1, 2012, through Aug. 16, 2017, with the number of reports filed relatively constant each year from 2014 through 2016 (Figure 3).

Figure 1 — ASRS Runway Incursion Reports Received, 2012–2017*

Source: U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration Aviation Safety Reporting Service (ASRS)

He said that the number of reported runway incursion events had generally trended upward since 2001, when 1,869 incursions (5 percent of the total number of ASRS submissions) were reported. But incursion reports have leveled off in the past few years, accounting for about 2.2 percent of all reports received; in 2016, that amounted to 2,018 reports, and through Aug. 16 of this year, 2,206 reports.

Overall, since 2012, more than 40 percent of runway incursion reports were filed by general aviation pilots and 36 percent by air carrier pilots, and about 90 percent of the events occurred at towered airports, he said.

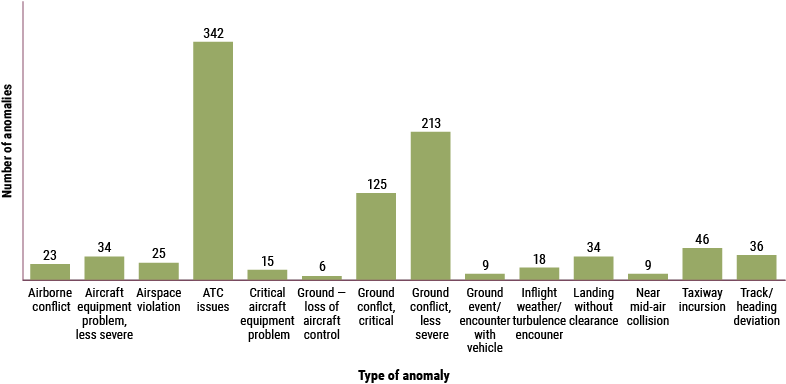

Some 770 records were singled out for more thorough study, which found that the top 15 “concurrent anomalies” were led by ATC issues, which involved 44 percent of the events (Figure 4). Other areas included several types of ground events, aircraft equipment problems, in-flight weather and turbulence encounters, and track or heading deviations.

Figure 4 — Top 15 Concurrent Anomalies

ATC = air traffic control

Source: U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration Aviation Safety Reporting System

Human factors were cited in 87 percent of event records. Among specific human factors issues were situational awareness (cited in 76 percent of records), communication breakdown (55 percent), confusion (53 percent) and distraction (31 percent).

In the 50 most recent records of communication breakdown, those filing reports to ASRS offered a number of explanations, including blocked or stepped-on radio transmissions, equipment issues, language barriers, memory lapses and misunderstood clearances.

Brauch cited one report in which a pilot had explained that he or she failed to verify that ATC instructions were intended for his aircraft, and added, “I assumed the takeoff clearance was for us and, due to partially blocked radio call, missed the fact that it was not for us.”

When ASRS personnel analyzed the 50 most recent reports of confusion, they noted that explanations ranged from airport marking and signage issues to airport layout, language barriers, weather and “untimely” or unclear ATC instructions.

One pilot explained, “As I came towards the end of what would be the downwind, I started to question whether I was understanding the layout of the runways. [The airport] has four runways in a set of two that are 30 degrees different from each other. It is a very confusing airport.”

A similar analysis of the 50 most recent reports of distraction revealed explanations citing airport construction, co-worker interruption or interference, equipment issues, use of nonstandard phraseology, traffic volume and weather.

“Contributing factors were numerous taxiway and runway closures due to construction,” one pilot explained. “I listened to ATIS [automatic terminal information service] and other NOTAMS [notices to airmen]. This is my home airport, so the construction was not new to me. Also, the flight was going to be long, with a fuel stop, and arrival weather considerations in (destination). This possibly distracted me from the non-standard taxi to [Runway] 22L and ending up thinking hold short of 22L instead of [Runway] 22R.”

Looking for Clarity

Existing data do not necessarily provide a clear picture of runway incursion trends, said Chris Devlin, portfolio manager of safety, standards and training at The MITRE Corporation.

“It’s clear that there was a significant decrease in the rate of incursions from 2000 to 2008; it’s less clear as to what has happened since that time,” Devlin told the forum.

“Since 2008 [when the FAA changed its definitions of runway incursions to match the definitions used by the International Civil Aviation Organization], depending on which methodology you choose, one could come to different conclusions” on whether the trend in runway incursions is flat, increasing or decreasing.

MITRE is examining a few incursions each year to better understand the inherent risks and to analyze the effectiveness of mitigations, he said.

“We don’t have the specificity in the data that we’re currently collecting to understand the full picture of what’s happened and, just as important, if a mitigation is in place — whether it’s an engineering control like ASDE-X or a procedural control like the signage and markings — we don’t have a way currently to determine whether that has effectively prevented a runway incursion. And so what we’re doing now is chasing a few events each year trying to understand the true risk in the system.”

Technological Improvements

Hart and several of those speaking to the forum noted that a series of technological advances have helped reduce the risk of runway incursion accidents, citing ASDE-X and the development of runway incursion warning systems designed to deliver ASDE information to drivers of airport surface vehicles, among other things.

Cockpit moving map displays with own-ship position “have the potential to provide similar immediate awareness to pilots,” Hart said.

Twenty of the busiest U.S. airports are scheduled to be equipped with runway status lights, he said, and many airports have taken action to improve signage and markings, to install elevated runway guard lights to indicate to pilots that an aircraft is about to enter an active runway, and to improve airport layouts.

Fee added, “The technology systems that have been put in place, the air traffic flight crew operational procedures and vehicle driver procedures that have been put in place, over time, have helped reduce risk, as well as the constant sharing of information and data to those operational groups.”

Notes

- NTSB. Aircraft Accident Report NTSB/AAR-07/05, Attempted Takeoff From Wrong Runway; Comair Flight 5191, Bombardier CL-600-2B19, N431CA; Lexington, Kentucky; August 27, 2006.

- Under the FAA’s runway incursion severity classifications, a Category A incursion is defined as “a serious incident in which a collision was narrowly avoided”; a Category B incursion is “an incident in which separation decreased and there is a significant potential for collision, which may result in a time-critical corrective/evasive response to avoid a collision”; a Category C incursion is “an incident characterized by ample time and/or distance to avoid a collision”; and a Category D incursion is an “incident that meets the definition of runway incursion such as incorrect presence of a single vehicle/person/aircraft on the protected area of a surface designated for the landing and takeoff of aircraft but with no immediate safety consequences.”

Featured image: © Palladadesign | iStockphoto