Surprising responses by an airline captain and flight attendants in the 17 minutes after their aircraft veered off the landing runway at a New York airport delayed the evacuation of 132 people from the McDonnell Douglas MD-88. The crewmembers’ actions bring to mind human factors in evacuations that have been addressed repeatedly in the past 20 years.1

The U.S. National Transportation Safety Board’s (NTSB’s) final report on the March 2015 runway excursion by the Delta Air Lines aircraft at LaGuardia Airport acknowledges the entire crew’s performance in the accident’s favorable outcome, with casualties limited to 29 passengers who suffered minor injuries (see “Lost in Reverse”).2

However, the report’s findings — as well as the findings in other relatively recent U.S. airline accidents3 — cover human performance failures that could have affected the outcome. They also note cabin safety procedures incongruent with prevailing best practices, opportunities to rethink today’s industry-wide assumptions, and known ways to enhance evacuation-related communication, coordination and training among pilots and flight attendants.

Key Findings

The report emphasizes five findings regarding cabin safety/evacuation and survival factors: “The flight and cabin crews did not conduct a timely or an effective evacuation because of the flight crew’s lack of assertiveness, prompt decision making and communication, and the flight attendants’ failure to follow standard procedures once the captain commanded the evacuation. The flight attendants were not adequately trained for an emergency or unusual event that involved a loss of communications after landing, and the flight attendants’ decision to leave their assigned exits unattended after the airplane came to a stop resulted in reduced readiness for an evacuation. This and other accidents demonstrate the need for improved decision making and performance by flight and cabin crews when faced with an unplanned evacuation.”

The aircraft crew was not mentioned in relation to one of the survival factors cited — insufficient timely and precise initial information about the accident’s details and the substantially damaged airplane’s exact location to enable aircraft rescue and fire fighting (ARFF) personnel to arrive as quickly as possible. A similar finding was, “Even though the initial uncertainty regarding the total number of passengers aboard the accident flight, including lap-held children, did not lead to any adverse outcomes, such uncertainty could be detrimental under other accident circumstances, especially if search and rescue efforts are needed.”

Safety Recommendations

The NTSB called on the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) to modify its evacuation-related guidance and training expectations for air carriers (specifically, those operating under Federal Aviation Regulations Part 121, Operational Requirements, Domestic, Flag and Supplemental Operations). The new guidance should instruct “flight attendants to remain at their assigned exits and actively monitor exit availability in all non-normal situations in case an evacuation is necessary.” A new element of flight attendant training programs should “include scenarios requiring crew coordination regarding active monitoring of exit availability and evacuating after a significant event that involves a loss of communications.”

The report’s safety recommendations also requested that the FAA convene a government-industry working group focused on ways to “improve flight and cabin crew performance during evacuations” involving Part 121 flight operations. This work ostensibly would include examining the issues of the LaGuardia accident and other recent accidents involving problematic evacuations. The objective is to update guidance for responding to emergencies, essentially specifying best practices for aircraft evacuation–related crew communication and coordination of their response. This guidance also would update crewmembers’ training and practice in decision making during emergencies.

The FAA also should clarify its existing guidance to all Part 121 air carriers to reinforce to crewmembers the importance of a reliable passenger count in evacuation scenarios and to reduce this risk of delaying the completion of search and rescue efforts, the NTSB report said. Specifically, the NTSB urged reiteration of the need for “precise information about the number of passengers aboard an airplane, including lap-held children, [and] making this information immediately available to emergency responders after an accident.”

In addition, the NTSB reiterated an earlier request, while pointing out the inter-agency history of interactions about issue-relevant rule making and guidance. The NTSB said, “Revise [FAA] Advisory Circular 120-48, ‘Communication and Coordination Between Flight Crewmembers and Flight Attendants,’ to update guidance and training provided to flight and cabin crews regarding communications during emergency and unusual situations to reflect current industry knowledge based on research and lessons learned from relevant accidents and incidents over the last 20 years.”

Crewmember Actions

Inclement winter weather was a factor in the MD-88 crew’s evacuation considerations and in the ARFF response to the accident, which occurred at the end of a 90-minute flight from Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport. This was the second flight of the planned trip on that day for the two pilots, one lead flight attendant stationed in the front of the cabin and two flight attendants (one also qualified as a lead flight attendant) stationed in the aft part of the cabin. Fatigue was not found to be a contributing factor.

Surface conditions at the airport were tower visibility 0.75 mi (1.21 km) in moderate snow, snowfall accumulation of 4 to 7 in (10 to 18 cm), high snowbanks piled alongside Runway 13 from plowing operations, freezing fog and temperature 28 degrees F (minus 2 degrees C). After yawing about 20 degrees during the landing rollout, the airplane came to a stop on the shoreline of Flushing Bay before reaching an engineered materials arresting system at the departure end of Runway 13.

The report summarizes the known threats immediately faced by the crew and passengers as follows: “After unexpectedly departing the paved runway surface, the airplane came to rest at a non-normal attitude with its nose over water and left wing damaged. The accident sequence also damaged the electrical systems, which resulted in the loss of the interphone and public address [PA] system as a means for communication.”

NTSB investigators said that in this situation, per the airline’s procedures, each flight attendant was expected to remain near an assigned exit and to maintain “a state of readiness for an evacuation,” a process including assessment of the exit status and interior/exterior situations. Because of the unusable interphone and PA system, however, “The two flight attendants in the aft cabin left their assigned locations and walked to the forward cabin (to obtain information from the flight crew and the lead flight attendant) while instructing passengers to stay seated and stay calm,” the report said. Part of the context for these actions was the airline’s flight attendant manual instructing cabin crews not to evacuate the airplane “if there was no immediate danger after 30 seconds.”

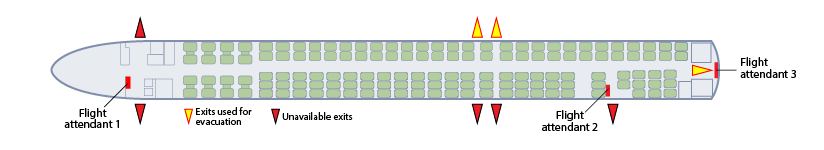

Source: National Transportation Safety Board

In interviews with NTSB investigators, the flight attendants described the actions they took between the time the aircraft stopped and the moment that they received their evacuation command from the captain. The lead flight attendant momentarily left her jumpseat at the request of nearby passengers to check on a passenger’s well being. She later reported to the captain seeing the bay just outside the left-side windows in the cabin and that the forward door exits were not suitable for safe evacuation. “She walked back to the 2L door to check its availability and, after returning to the front of the cabin, told the captain that the exit looked ‘OK’ but [she] expressed concern that the slide might not properly deploy because of the snow and debris associated with the accident,” the report said.

One of the aft flight attendants initially shouted commands for passengers to stay seated and calm, and the other initially spent time checking the condition of passengers. They later reported to the captain the left-wing damage they had seen and their determination that right-side overwing exits would be usable for evacuation.

The captain left the flight deck and discussed the situation face to face with all the flight attendants together. These crewmembers discussed the status of the forward and 2L door exits; the aft flight attendant assigned to the tailcone exit said she did not know its status. As one of the flight attendants returned to the aft cabin, a passenger told her that a firefighter “was motioning to open the right overwing exits, to which she replied, ‘No, we need to wait until our captain instructs us to evacuate,’” the report said.

Meanwhile, from outside the aircraft flight deck, another firefighter told the first officer that all occupants should evacuate the airplane through the right overwing exits because of fuel leaking from the left wing. The report said, “The first officer relayed this information to the captain, and the captain told the flight attendants that they should prepare for an evacuation using the right overwing exits. Soon afterward, the captain retrieved the forward megaphone, gave it to the lead flight attendant, and told her to begin an evacuation.4 … Given that the airplane was stopped off the runway at an unusual attitude and with damage, the captain’s decision to evacuate the airplane should have come earlier in the sequence of events and before the request from ARFF personnel to evacuate.”

However, the investigators concluded from videos, interviews and other sources that flight attendants then were confused about the timing of initiating the evacuation. As a result, NTSB determined that the evacuation began about six minutes after flight attendants first told passengers they would have to evacuate — i.e., about 12 minutes after the airplane came to a stop. The report said the elapsed time for the evacuation — from when the airplane came to a stop until all passengers were off the aircraft — was more than 17 minutes.

“When the captain commanded the evacuation, the flight attendants were expected to immediately begin the evacuation and follow their procedures for evacuating the cabin as expeditiously as possible. … Videos taken by a passenger in the aft cabin showed that flight attendants first indicated their intent to evacuate the airplane … after the airplane came to a stop, when the lead flight attendant instructed passengers that they would need to evacuate ‘very calmly, slowly, and single file.’

“The passengers were also instructed to remain seated and leave their carry-on baggage but were then told that they could stand [in the aisle] to retrieve ‘coats, hats, scarves, [and] gloves’ because ‘it’s cold outside.’ Many passengers were then seen on the videos standing and moving around in the aisle. … Although the flight crew learned about the fuel leak from [an ARFF] first responder before the evacuation, the flight crew did not share that information with the flight attendants, who learned about the fuel leak from a first responder after the evacuation had already begun.”

Passenger Video From Delta Air Lines Flight 1086

Source: U.S. National Transportation Safety Board

When the evacuation began, the flight attendants’ commands included telling passengers to discontinue using mobile phones while exiting. During the evacuation, the safety of using of the tailcone exit temporarily became uncertain because of water seen in the area and the exit’s inoperative slide. Regarding evacuation duties and procedures in the airline’s flight attendant manual, as well as related training, investigators found no procedures for communicating during an emergency in cases of loss of the PA system and interphone. This situation also was not covered by the flight attendant training curriculum.

These factors explained, from the investigators’ standpoint, the flight attendants’ confusion about evacuation timing when the MD-88 came to rest. Cabin crew actions showed consistency with existing procedures and training. The report paraphrased the manual’s guidance that “if the flight crew instructed the passengers to remain seated after an emergency or unusual situation, the flight attendants were to await evacuation instructions from the flight crew (unless the conditions were life threatening, in which case the flight attendants had the authority to initiate an evacuation).”

Investigators suggested that the megaphones were one evacuation tool that these flight attendants could have retrieved from forward and aft overhead bins before leaving assigned exits, and could have used as an alternate communication means under the circumstances. They also said another solution to the initial communication breakdown could have been using one of the aft flight attendants to relay information while the other two performed duties at their assigned positions.

The NTSB’s analysis of the cabin crew’s actions also pointed out that a key risk in leaving their assigned exits — given the apparent possibility of the captain commanding an evacuation — was degradation of overall readiness. “If the flight crew had commanded an evacuation or a life-threatening situation had occurred while the flight attendants were away from their assigned exits (such as the leaking fuel igniting outside the airplane), passengers blocking the aisle could have prevented the flight attendants from reaching and opening their assigned emergency exits,” the report said. “The NTSB could not find any specific FAA guidance that emphasized the need for flight attendants to remain at their assigned exits during a non-normal situation after landing.”

Past Lessons Learned

The report noted that the NTSB has investigated other accidents in which similar cabin safety/evacuation problems occurred and has issued related safety recommendations. Details of examples can be found in the LaGuardia accident report. Key points or lessons learned from a few of the accidents cited can be distilled and paraphrased as follows.

When the aircraft stopped after one 1996 runway excursion, the purser and three flight attendants found the interphone inoperative but did not use megaphones as an alternative communication tool. “The purser was unaware that his announcements over the public address system were only audible in the forward cabin, so passengers and flight attendants in the aft cabin did not receive any information,” NTSB said, and an effort to use a flight attendant traveling as a passenger to relay messages failed. This led to a safety recommendation on alternate emergency communication.

In another accident in 1996, because of the inoperative interphone, flight attendants in the aft section of an airliner commanded and began an evacuation at the same time that the flight crew was commanding passengers to remain seated.

Regarding the repetition of similar circumstances and associated sub-optimal crew responses over the years, the LaGuardia accident report said, “The NTSB’s June 2000 safety study on emergency evacuations of commercial airplanes5 found continuing communication and coordination problems among flight and cabin crewmembers during airplane evacuations. … Joint evacuation exercises for flight and cabin crews could be effective in resolving such problems.”

The FAA responded to the latter safety recommendation, commenting then that joint exercises were not common and should not be required, the report said. Other NTSB safety recommendations cited in this report address crewmembers’ unwarranted delays in making a decision to evacuate.

Notes

- NTSB. Flight Attendant Training and Performance During Emergency Situations. Special Investigation Report NTSB/SIR-92/02, Washington: National Transportation Safety Board, 1992.

- NTSB. Runway Excursion During Landing, Delta Air Lines Flight 1086, Boeing MD-88, N909DL, New York, New York, March 5, 2015. Accident Report NTSB/AAR-16/02, Sept. 13, 2016. The report said the flight crew was landing on Runway 13 at LaGuardia Airport when the airplane sustained substantial damage as it “departed the left side of the runway, contacted the airport perimeter fence, and came to rest with the airplane’s nose on an embankment next to Flushing Bay.”

- The August 2010 issue of ASW, for example, summarized areas for evacuation improvement identified during investigation of the ditching of US Airways Flight 1549 <flightsafety.org/asw-article/survival-on-the-hudson-expanded-version/>.

- FSF Editorial Staff. “Mastery of Megaphones Reinforces Cabin Crew Control of Evacuations.” Cabin Crew Safety, November–December 2003. One cited report said, “Even though the flight attendant in charge knew that the airplane PA system was inoperative, he did not remove the megaphone to make the announcements prescribed in the company briefing format. … NTSB concludes that had this been done, the emergency briefings probably would have been heard, by more, if not all, of the passengers, and in any event, in greater detail.”

- NTSB. Emergency Evacuation of Commercial Airplanes. Safety Study NTSB/SS-00/01, Washington: National Transportation Safety Board, 2000.

Featured image: © Tewin Kijthamrongworakul (Brostock) | Adobe Stock