A “significant number” of active pilots are suffering from depression, according to a report by health researchers at Harvard University’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health.1

The report, published Dec. 15, 2016, in Environmental Health said that the conclusions were based on a web-based survey of 3,485 pilots; of that number, 1,848 airline pilots responded to the patient health questionnaire, including 233 (12.6 percent) whose answers were interpreted as meeting the questionnaire’s definition of depression. Of 1,430 respondents who said they had worked as an airline pilot in the previous seven days, 193 (13.5 percent) met the definition of depression. Seventy-five survey participants (4.1 percent) reported that they had experienced suicidal thoughts in the previous two weeks.

Depression occurred at higher levels among pilots who used sleep-aid medication and those who reported experiencing sexual harassment or verbal harassment, the report said.

The survey’s results have “limited generalizability,” the report said.

Nevertheless, it added, “Hundreds of pilots currently flying are managing depressive symptoms, perhaps without the possibility of treatment due to the fear of negative career impacts. … There are a significant number of active pilots suffering from depressive symptoms.”

The survey was prompted by the March 24, 2015, crash of Germanwings Flight 9525, an Airbus A320 that accident investigators concluded was intentionally flown into the ground in the French Alps by its suicidal first officer. All 150 people in the airplane were killed.2

Past studies have shown that it is rare that a commercial pilot uses an aircraft to commit suicide (or murder-suicide, in cases that result in the deaths of passengers and other crewmembers), and that there is no identifiable pattern of motivations that can identify those most likely to perpetrate the events.3 One of the most recent studies — discussed in a 2016 report by researchers from New Zealand and the United States — found that insufficient data existed to suggest that mental illness had a significant role, and that perpetrators often had financial or relationship problems or other stressors (“No Clear Pattern,” ASW, 9/16).

Perhaps the First

The report noted that an estimated 350 million people worldwide have clinical depression, also called major depressive disorder. The ailment is characterized by at least two weeks of “depressed mood or loss of interest,” along with at least four other symptoms associated with depression — such as, according to the American Psychiatric Association, “feeling sad or having a depressed mood; loss of interest or pleasure in activities once enjoyed; changes in appetite (weight loss or gain unrelated to dieting); trouble sleeping or sleeping too much; loss of energy or increased fatigue; increase in restless activity (e.g., hand-wringing or pacing) or slowed movements and speech; feeling worthless or guilty; difficulty thinking, concentrating or making decisions; and thoughts of death or suicide.”4

There are about 140,000 airline pilots worldwide, with about half that number in the United States, the report said. Pilots’ mental disorders must be disclosed by the pilots themselves, and aeromedical experts generally agree that, as the report said, “under-reporting of mental health symptoms and diagnoses is probable among airline pilots due to the public stigma of mental illness and fear among pilots of being ‘grounded,’ or not fit for duty.”

The report’s authors believed that anonymous surveying could lessen some qualms about pilot reporting of depression and other mental health issues.

“The objective … was to provide a more accurate description of mental health among commercial airline pilots underscoring symptoms related to clinical depression,” the report said. “This study did not conduct clinical interviews of survey respondents to confirm diagnosis of depression nor did it have access to medical records.”

The report characterized the study as perhaps the first — other than reports derived from aircraft accident investigations, regulated health examinations or “identifiable self-reports” — to examine the mental health of airline pilots, focusing on depression and suicidal thoughts.

The anonymous, web-based survey was administered between April and December 2015 to pilots who had been recruited from labor unions, airline companies and airports. In all, 3,485 pilots in more than 50 countries were surveyed; of that number 1,837 completed the entire survey, and 1,866 completed at least half. Some 1,848 respondents completed portion of the survey known as the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9).

Of the 1,826 respondents who provided information about their age, half were middle aged, with a median age of 42 for female pilots and 50 for male pilots. Half the respondents had worked at least 16 years as a pilot. In nearly all age categories, up to age 80, there were pilots whose survey responses met the definition of depression.

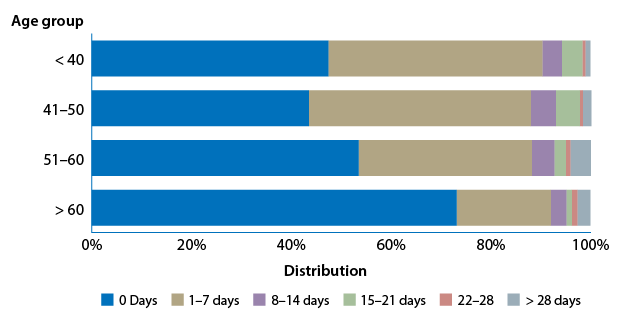

“The number of pilots self-reporting having at least one day of poor mental health during the past month ranged from 94 (26.9 percent) among those over age 60 to 273 (56.5 percent) among 41 to 50 years,” the report said. “Forty-seven (9.6 percent) respondents up to age 40 and 110 (11.9 percent) age 41 to 60 reported having at least eight days of poor mental health during the past month.”

Figure 1 — Distribution of Days of Poor Mental Health by Age Group

Source: Wu, Alexander C.; Donnelly-McLay, Deborah; Weisskopf, Marc G.; McNeely, Eileen; Betancourt, Theresa S.; Allen, Joseph G. “Airplane Pilot Mental Health and Suicidal Thoughts: A Cross-Sectional Descriptive Study Via Anonymous Web-Based Survey.” Environmental Health Volume 15 (2016).

In addition, greater percentages of women (55.2 percent, or 139) than men (45.6 percent, or 697) reported at least one day of “poor mental health” during the previous month and reported having previously been diagnosed with depression (12 women, or 4.7 percent, compared with 46 men, or 2.9 percent), the report said.

Female pilots, who make up about 4 percent of all commercial airline pilots, made up 13.7 percent of the study population, the report said, noting that the over-sampling was intentional, and designed to gain more information from this minority group.

Geography and Culture

The report’s authors examined the relationship between pilots’ cultures and their reporting of depression, noting that 1,576 respondents (85.5 percent) took the survey in countries that exhibited more “western cultural influence (i.e., countries in North and South America, Europe or Australia)”; 267 respondents (14.5 percent) took the survey in counties that were less culturally western (such as those in Asia).

“Countries with more western cultural influence had a lower percentage of pilots meeting depression threshold than others” — 172 respondents, or 10.9 percent, from countries with Western influences reported depression, compared with 60 respondents, or 22.5 percent) from countries with less Western influence, the report said.

“Furthermore,” the document added, “61 participants (3.9 percent) initiating surveys in more culturally Western countries, compared to 14 (5.3 percent) in less Western countries reported having thoughts of being better off dead or [thoughts of] self-harm within the past two weeks.”

The authors hypothesized two possible explanations.

“One reason is [that] the type of culture the pilots identify themselves with and country of survey initiation is not an accurate match,” the report said. “If … more Western-culture pilots were flying longer trips (such as from Western- to Eastern-culture countries), compared to … less Western-culture pilots, then these more Western-culture pilots may be more likely to initiate surveys in less Western-culture countries because of more downtime between flights. This could result in the misclassification of less Western-culture pilots appearing to have higher prevalence of meeting [the] threshold for depression.”

The report said possible underlying factors might be associated with longer trips that increased the risk of disruption of the body’s natural circadian rhythms and increased the pilots’ exposure to occupational factors that might be related to mental illness.

This misclassification also “could occur the other way, with healthier … less-Western culture pilots flying to more Western-culture countries and initiating surveys, thus making Western pilots appear healthier,” the report said.

The second hypothesis is that pilots from more Western-culture countries actually have a lower prevalence of meeting the threshold for depression. The report cautioned, however, that researchers could not “validate what culture pilots identify with due to lack of data” and that the study had gathered limited data on pilots outside Western-culture countries.

When responses of more Western-culture pilots were compared with those of less Western-culture pilots, the prevalence of suicidal thoughts was not significantly different, the report said.

The report also noted that the results of the comparison do not align with patterns observed in the results of other mental health surveys, which typically find a greater prevalence of mood disorders among people in more Western-culture countries.

Providing Assistance

Although the study did not evaluate pilot access to mental health treatment, the report noted that airline pilots — like military personnel, firefighters, police officers and others in high-stress occupations — may encounter “occupational and individual barriers to seeking treatment.” Among those barriers are shift work, long and continuous work hours, and the stigma of admitting to work-related mental health issues, the report said.

“Since mental health problems are prevalent among our participants and may be exacerbated in high-stress work situations, we agree with the argument that organizations are responsible for ensuring employees who develop mental health problems receive timely mental health treatment,” the report said.

The report recommend combining traditional cognitive behavioral treatment (CBT) with work experience, which has shown to promote a speedier return to work for people who have been granted leave to deal with mental health issues. The report also noted that research has shown that internet-based CBT is effective in treating mild to moderate depression, especially when combined with face-to-face psychological treatment.

Despite the limitations of the study, the report said that it “fills an important gap of knowledge by providing a current glimpse of mental health among commercial pilots” and raises concerns about pilots’ mental health issues.

“Poor mental health is an enormous burden to public health worldwide,” the report said. “The tragedy of Germanwings Flight 9525 should motivate further research into assessing the issue of pilot mental health. Although current policies aim to improve mental health screening, valuation and record keeping, airlines and aviation organizations should increase support for preventative treatment.”

Notes

- Wu, Alexander C.; Donnelly-McLay, Deborah; Weisskopf, Marc G.; McNeely, Eileen; Betancourt, Theresa S.; Allen, Joseph G. “Airplane Pilot Mental Health and Suicidal Thoughts: A Cross-Sectional Descriptive Study Via Anonymous Web-Based Survey.” Environmental Health Volume 15 (2016).

- Bureau d’Enquêtes et d’Analyses (BEA). Final Report: Accident on 24 March 2015 at Prads-Haute-Bléone (Alpes-de-Haute-Provence, France) to the Airbus A320-211, Registered D-AIPX, Operated by Germanwings. March 2016.

- Kenedi, Christopher; Friedman, Susan Hatters; Watson, Dougal; Preitner, Claude. “Suicide and Murder-Suicide Involving Aircraft.” Aerospace Medicine and Human Performance Volume 87 (April 2016): 388–396.

- American Psychiatric Association. What Is Depression?

Featured image: © ambrozinio | 123RF