The 2015 crash of a Germanwings Airbus A320 in the French Alps focused the public’s attention on mental health in an aviation context. The co-pilot, killed along with the other 149 passengers and crew, was blamed for the crash, which the French Bureau d’Enquêtes et d’Analyses (BEA) said resulted from “the deliberate and planned action of the co-pilot, who decided to commit suicide while alone in the cockpit.”

As if to underline the issue, a 2016 study found that, of 1,837 pilots responding to an online survey on mental health, over 12 percent met the threshold for depression and 4 percent reported having had suicidal thoughts.1 Such individuals often avoid seeking help because of potentially negative career impacts. One method of providing support for people with apparently intractable problems is a peer assistance network (PAN). Psychologists have identified many advantages of peer intervention, and occupational networks have been established worldwide utilizing the benefits of non-judgmental empathetic listeners, familiar with local work issues, who provide support for their peers.

A 1983 report presents a strong case for the efficacy of social support, specifically because of its effect on ameliorating stress and because it aids “positive adjustment and personal development.”2 The report defines social support as individuals who identify themselves as not only caring about us, but also as making themselves available to us — the essence of a PAN volunteer.

Mid-20th century research concluded that, because of the human need to bond with people who are similar to ourselves, interactions with peers are more comfortable because of common characteristics.3 A later study explored the ease of interacting with others whose lives and problems are similar to our own. This experiential bond is another area where peers excel.4

A social-learning theory developed in 1969 predicted that peers, because they share the trials and tribulations of their co-workers, are credible role models who have the potential to encourage positive change.5 Finally, the helper-therapy principle makes volunteering more beneficial than receiving support. Someone who volunteers (and thereby demonstrably cares), and who also is in our social group, understands the problems of our workplace and has potentially overcome those problems, is approachable and credible.6 The added value is that the helper also benefits.

For the many aviation workers who work on contracts and are away from home for lengthy periods of time, the fall-back communication method of social media or a voice over internet protocol communication method, such as Skype or Facetime, causes them to miss many of the fundamental requirements of social interaction. As a result, they experience reduced cognitive and emotional investment, the loss of wordless interactions such as tone of voice and facial expressions, and the important sharing of another’s emotional state — a sharing that enables empathy.7 A peer provides all these benefits in an accessible, face-to-face setting, enabling early intervention before a problem becomes an issue.

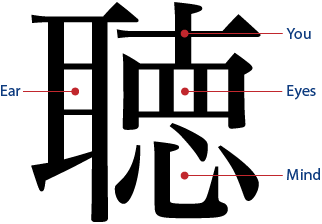

Figure 1 — Japanese Character for Listen

Source: Nick Carpenter

Individuals must find their own answers to their problems, and this can be facilitated by trained reflective listeners. It is interesting to consider the Japanese Kanji character for listening. It is a composite symbol made up of other symbols as illustrated in Figure 1. The left side of the character emphasizes the ear, the right side illustrates the importance of mindful attention to the message-sender. Often when communicating, we are more intent on forming our reply than on trying to understand the underlying issue affecting the other person. Reflective listening ensures that we understand the communicator’s message by having us repeat it back to them in our own words. For example:

Colleague 1: “I worked so hard on that project, and when I presented it nobody was interested.”

Colleague 2: “That must have made you so angry?”

Colleague 1: “No, it made me feel unwanted and insecure. They ask me to do the work but ignore the results!”

A justified inference from Colleague 2 that being ignored would be annoying is wrong. For Colleague 1, the slight undermined his or her confidence, an important consideration when attempting to rationalize the issue and find a way to rebuild confidence. Communicating is hard work, but probably not as hard as avoiding our natural instinct to offer solutions.

Evidence supports the efficacy of peers offering early, confidential support to their colleagues and the benefits of non-judgmental listening, but making it happen is “simple, but not easy.”

PAN, to maintain confidentiality, must remain independent of management. Monetary demands are limited because volunteers give their time freely, but third-party liability insurance is not cheap in our litigious age, courses cost money, and both volunteers and those that they help may need time free of work to resolve issues. Management buy-in is important as PAN volunteers may, when concerned about a peer, need to ask that people be removed from duty. PAN volunteers can be contacted directly by telephone but are equipped with a simple identification lanyard that identifies them to their peers, enabling many contacts to be made; in the main, they involve a short, reassuring chat. There is, of course, concern that some individuals initiating contact may need the help of a professional. When someone contacts PAN, he or she is aware of having a problem, and, in the case of Qantas Group pilots, who have access to an Australia-based PAN, free professional help is but a telephone call away. For this reason, encouraging someone to stay away from work is relatively straightforward. However, volunteers are given a very clear escalation strategy to encourage peers to reconsider their availability for work in case of risk for the safety of their contact or the travelling public. Many PAN organizations keep de-identified statistics of contacts to their members. They serve two purposes: to illustrate PAN’s necessity and to monitor trends. Finally, Mayday Stiftung — a worldwide organization based in Germany that supports crewmembers after stressful incidents and accidents — claims that the reduction in sickness made possible by a PAN benefits airlines in more ways other than simply by reducing costs..

It is fair to say that PANs have been empirically proven to be effective, but they also have ecological validity as most humans, amateur psychologists that they are, are keenly aware of the benefits of talking. Setting up a PAN requires perseverance, as immediate buy-in by cynical employees takes time. Finding non-judgmental listeners with the ability to maintain confidentiality is equally challenging. However, when PANs are up and running, the benefits — keeping employees from hiding their problems by offering a safe harbor, de-stigmatizing mental health issues and, potentially, expanding a just culture within the workplace while keeping employees in their jobs — make the challenges worthwhile.

Nick Carpenter, a pilot with military and airline experience, holds a master’s degree in psychology and is the operations manager at the Aviation Safety Institute in Australia.

Notes

- Wu, A.C.; Donnelly-McLay, D.; Weisskopf, M.G.; McNeely, E.; Betancourt, T.S.; and Allen, J.G. “Airline pilot mental health and suicidal thoughts: a cross-sectional descriptive study via anonymous web-based survey.” Environmental Health Volume 15 (2016, No. 121).

- Sarason, I.G.; Levine, H.M.; Basham, R.B.; and Sarason, B.R. “Assessing social support: The Social Support Questionnaire.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Volume 44 (1983, No. 1): 127–139.

- Festinger, L. “A Theory of Social Comparison Processes.” Human Relations (1954, No. 7): 117–140.

- Veinot, T.C. “‘We have a lot of information to share with each other’: Understanding the value of peer-based health information exchange.” Information Research 15.4 (2010): 15–4.

- Bandura, A. “Social-learning theory of identificatory processes.” Handbook of socialization theory and research, 1969. 213–262.

- Bracke, P.; Christiaens, W.; and Verhaeghe, M. “Self-Esteem, Self-Efficacy, and the Balance of Peer Support Among Persons With Chronic Mental Health Problems.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology Volume 28 (2008, No. 2): 436–459.

- Nummenmaa, L.; Glerean, E.; Viinikainen, M.; Jääskeläinen, I.P.; Hari, R.; and Sams, M. “Emotions promote social interaction by synchronising brain activity across individuals.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America Volume 109 (2012, No. 24): 9599–9604.

- Mackay, H. The Good Listener: Better Relationships through Better Communication. Sydney, Australia: Pan Macmillan, 1998.

Featured image: composite, Susan Reed using icons by © macrovector | VectorStock