The likelihood of encounters between small (2 kg [4 lb] or less) drones and other air traffic is increasing as the number of small drones increases, but the potential risk to passengers and crew should a drone and a manned aircraft collide depends on a number of factors, including the size and design of the manned aircraft and the speed at which the vehicles are travelling, according to a new U.K. Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) report titled “Drone Safety Risk: An Assessment.”

“CAA’s review of existing risk evidence indicates that drones do pose a potential safety risk to other airspace users, though commercial aircraft are designed and manufactured to high standards,” said the report, which was published in January. “Light aircraft and helicopters are designed and built to different requirements, and therefore, the consequences of a small drone colliding with these forms of aircraft may be different from larger commercial aircraft. Further research is required by aircraft certification authorities and aircraft manufacturers to better understand the damage implications of a collision, and as data about usage becomes available, the probability of collision.”

At the time the CAA report was written, there had been seven confirmed cases of direct in-flight contact between drones — also known an unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), among other terms — and civil or military manned aircraft, the CAA said. Included on the list, which was based on data from the Aviation Safety Network’s (ASN’s) drone database, were a Nov. 1, 2017, collision between an Aerolíneas Argentinas Boeing 737-800 and a drone near Buenos Aires Jorge Newberry Airport; the Oct. 12 collision of a Skyjet Beechcraft A100 King Air and a drone 7 mi (11 km) from Quebec City, Canada; and the Sept. 21 collision between a consumer drone and a U.S. Army Sikorsky UH-60 Black Hawk helicopter near Staten Island, New York (see “Incomplete Knowledge”).

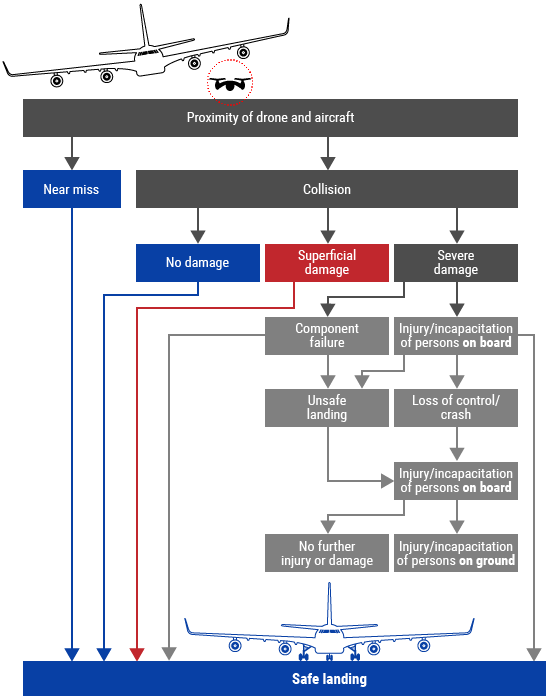

Example of Potential Events Following a Collision

Source: U.K. Civil Aviation Authority

In all three of those cases, as well as in three of the other four confirmed drone collisions in the ASN database, damage to the manned aircraft was reported as minimal. The exception was an Aug. 15, 2011, collision between a U.S. Air Force Lockheed C-130 and a RQ-7 Shadow UAV, a military UAV that weighs more than 350 lb (159 kg) and has a wingspan of 20 ft (6 m). Damage to the C-130 was substantial, but the aircraft landed safely.

None of the confirmed collisions occurred in the United Kingdom, but the number of occasions in which pilots have reported suspected drones in proximity to their aircraft in the U.K. is increasing, the report said, adding that there were 59 such occasions between April 2016 and March 2017. Two involved large passenger aircraft near London Heathrow Airport, leading to concerns being voiced in Parliament. In addition, a July 2017 incident in which an object believed to be an drone was near London Gatwick Airport led to a the runway being closed briefly and flights diverted.

Since then, there have been other high-profile incidents. On Oct. 25, the flight crew of an Airbus A321 on approach to Heathrow’s Runway 27L reported seeing a three- or four-engine white drone pass over the first officer’s window at a range of 5 ft (2 m), according to a U.K. Airprox Board report. The crew thought the drone had passed so close that it must have collided with the aircraft’s tail, but no tangible evidence of a collision was found after the aircraft landed.

On Nov. 3, an A320 was on short final for Runway 23R at Manchester when a medium sized quadcopter was seen 50 ft (15 m) to the right and 50 ft below the airliner. In this case, neither pilot on the flight deck saw the drone, but an A320 first officer travelling in the passenger cabin reported it.

More recently, the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) confirmed in early February that it is investigating an airliner encounter with a UAV in which a Frontier Airlines passenger aircraft on approach to land at McCarran International Airport in Las Vegas flew beneath a drone, which captured the event on video. The video eventually was posted on the internet.

The event captured on the video drew swift condemnation. The Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International (AUVSI), a U.S.-based nonprofit dedicated to advancement of unmanned systems and robotics, said, “All UAS operators need to understand their aircraft, stay well clear of manned aircraft and adhere to the law. AUVSI supports strict enforcement against careless and reckless operators who endanger the safety of the airspace and violate the law.”

AUVSI and a number of other interested stakeholders, including the Commercial Drone Alliance, the Drone Manufacturers Alliance, the Small UAV Coalition, the Aerospace Industries Association and the Academy of Model Aeronautics, subsequently sent a letter to Acting FAA Administrator Daniel Elwell expressing concern about the event and calling for swift action. “This careless and reckless behavior endangers the safety of our airspace for all users — both manned and unmanned. We urge the FAA to use its full authority to investigate, identify and apprehend the operator of this UAS flight and prosecute them to the fullest extent of the law. We also encourage the FAA to work with law enforcement in Las Vegas and Nevada to pursue all applicable charges within their authority.”

The CAA report said the agency has undertaken an assessment of available information about the likelihood of an unintentional drone collision and the severity of any possible impact between an aircraft and a small UAV. The CAA found that the drones most likely to end up in proximity to manned aircraft are smaller drones flown by operators who either do not know the aviation safety regulations or have chosen to ignore them.

The report also said it is considered “unlikely” that a small drone would cause significant damage to a modern turbofan jet engine and that, even if it did, a multi-engine aircraft likely would still be able to land safely.

Damage to an aircraft windscreen would depend on the speed at which a drone and an aircraft collided and the type of aircraft involved. The likelihood of a small drone being in the proximity (defined as visual line of sight) of a passenger aircraft when it is travelling fast enough to potentially damage a windscreen is about 2 per million flights, the report said. “The likelihood of a small drone actually hitting a passenger aircraft windscreen at sufficient speed to rupture it is very much smaller than the probability of it being in the proximity of an aircraft.”

The windscreens of small helicopters and light aircraft are more susceptible to rupture if struck by a small drone, even flying below normal cruise speed. Helicopters face the added risk of susceptibility of their rotors to damage from a collision, and their operating patterns typically involve lower-level flying and takeoff and landing from a range of sites, the report said.

Because of their greater size and weight, larger drones could potentially cause more damage in a collision, but there are fewer of them. “The increased severity inherent in collisions involving heaver drones is therefore offset by the fact that such drones will be fewer in number due to the higher cost and are likely to be used by more informed operators, often for commercial purposes,” the report said.

CAA pointed out that its drone risk safety assessment was based on observed numbers of reported drone proximity events, and that comprehensive data about the frequency and nature of drone use is very limited “and therefore a reliable predictive model that would enable an assessment of changes to key risk factors is not possible at the current time.”

In outlining next steps, the report said that a focus in the near future should be on improving the understanding of the potential severity of impact between a small drone and different categories of aircraft, particularly general aviation aircraft and small helicopters. Another focus area is the development of mitigation techniques that would help minimize the chances of drones coming into proximity with manned aircraft, including technical solutions that can be built into drones by manufacturers, such as height or distance limiters.

In outlining next steps, the report said that a focus in the near future should be on improving the understanding of the potential severity of impact between a small drone and different categories of aircraft, particularly general aviation aircraft and small helicopters. Another focus area is the development of mitigation techniques that would help minimize the chances of drones coming into proximity with manned aircraft, including technical solutions that can be built into drones by manufacturers, such as height or distance limiters.

CAA said the conclusions of its review support its current drone priorities, which are to:

- Continue its high-profile education and communications campaign to inform drone operators about how to fly responsibly;

- Define and publish geo-fenced areas to set electronic no-fly zones;

- Strengthen the education and accountability of operators through mandatory training and registration of drone operators; and,

- Link drone registration to the electronic conspicuity of drone flights and all other flights to help operators maintain safe separation from other airspace users and aid authorities in taking enforcement action against irresponsible drone operators.

Featured image: © pixone3d | Adobe Stock

Drone code cover: U.K. Civi Aviation Authority