An unexpected type of fatigue cracking led to the sudden detachment of the main rotor from an Airbus Helicopters EC225 LP Super Puma, and the helicopter’s subsequent crash on a small North Sea island while carrying oil workers from an offshore oil platform to Bergen, Norway, the Accident Investigation Board Norway (AIBN) says.

The April 29, 2016, crash killed both pilots and all 11 passengers; the CHC Helikopter Service helicopter was destroyed.

In its final report, issued in July, the AIBN said that the accident resulted from a fatigue fracture in a second-stage planet gear in the epicyclic module of the main rotor gearbox (MGB).

The fatigue fracture initiated from a “surface micro-pit in the upper outer race of the bearing, propagating subsurface while producing a limited quantity of particles from spalling [flaking], before turning towards the gear teeth and fracturing the rim of the gear without being detected,” the report said.

Investigators concluded that “the combination of material properties, surface treatment, design, operational loading environment and debris gave rise to a failure mode which was not previously anticipated or assessed.”

The AIBN report emphasized that neither crew handling nor maintenance actions played any part in the accident, adding, “The failure developed in a manner which was unlikely to be detected by the maintenance procedures and the monitoring systems fitted to [the helicopter] at the time of the accident.”

In the aftermath, however, the AIBN issued a dozen safety recommendations, including one that called on the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) to commission research into the development of fatigue cracks “in high-loaded, case-hardened bearings in aircraft applications.”

‘Everything Was According to Plan’

The day of the accident, the pilots checked in at Bergen Airport Flesland at the prescribed time, 45 minutes before their scheduled departure, planned their first flight to the Gullfaks oil field in the North Sea, and inspected the helicopter. They flew the accident helicopter to the Gullfaks C platform, leaving Flesland at 0702 local time and returning at 0851.

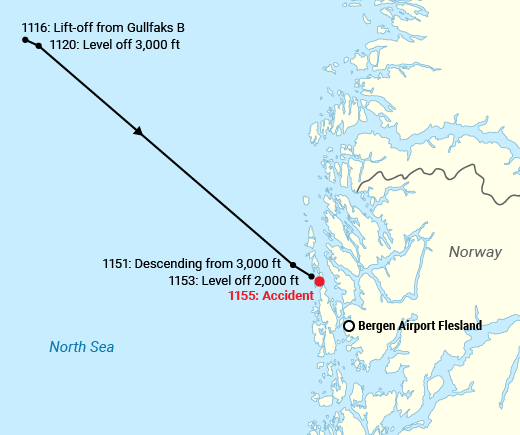

The helicopter departed from Flesland on its second round trip at 1005 and landed at the Gullfaks B platform, where outbound passengers disembarked and 11 passengers boarded for the inbound flight. The helicopter lifted off from the platform at 1116 and climbed to 3,000 ft.

“Everything was according to plan,” the report said. Shortly before reaching the coast, the helicopter descended to 2,000 ft and maintained that altitude for about one minute.

“Suddenly the engine torque dropped significantly and the main rotor started to tilt erratically,” the report added. “During this period, the helicopter climbed about 120 ft before the main rotor detached and the helicopter started to descend, following a ballistic curve towards the ground.”

The helicopter rolled and yawed right, then rolled slowly left as its nose pointed toward the ground. It struck the ground on Storeskitholmen Island about 1155, sparking a fire that burned about 3,000 sq m (0.7 acres) of heather. Most of the wreckage then slid into the sea.

The main rotor separated from the helicopter and flew “in a wide, erratic descending left hand turn,” landing on the island of Storskora.

A number of people witnessed the accident, and many told accident investigators that they heard a loud noise and a bang just before they saw the main rotor separate. Several said they saw yellowish red flames coming from the engines after the rotor separation.

Video recordings from several people on a nearby boat or on the ground showed the helicopter, after the rotor had separated, falling toward the ground, and the rotor continuing to rotate during its descent.

Search-and-Rescue Work

The helicopter’s 44-year-old commander received his training in Italy and later worked in a search-and-rescue squadron. He was hired as an AS332 L2 co-pilot at CHC Helikopter Service in 2007 and became an AS332 commander the next year. In 2015, he became a commander on EC225 LPs. The 6,100-hour pilot held an air transport pilot (ATP) license for helicopters and had been an instructor pilot since 2010.

The co-pilot, 57, had 11,184 flight hours and an ATP license for helicopters. He had trained at a civilian flight school in the United States and began working as a Super Puma co-pilot at CHC in 1989. He became an EC225 LP commander in 2009.

The operator was founded in 1956 as Scancopter-Service AS, renamed in 1966 as Helikopter Service and became part of CHC Helicopter’s global operations as CHC Helikopter in 1999. At the time of the accident, CHC Helikopter had 39 helicopters, five bases, additional offshore installations and 400 employees.

The accident helicopter was manufactured in 2009 and had accumulated 1,340 flight hours. It had been configured for two crewmembers and 19 passengers. Calculations determined that at the time of the crash, the helicopter was within its weight and center of gravity limitations.

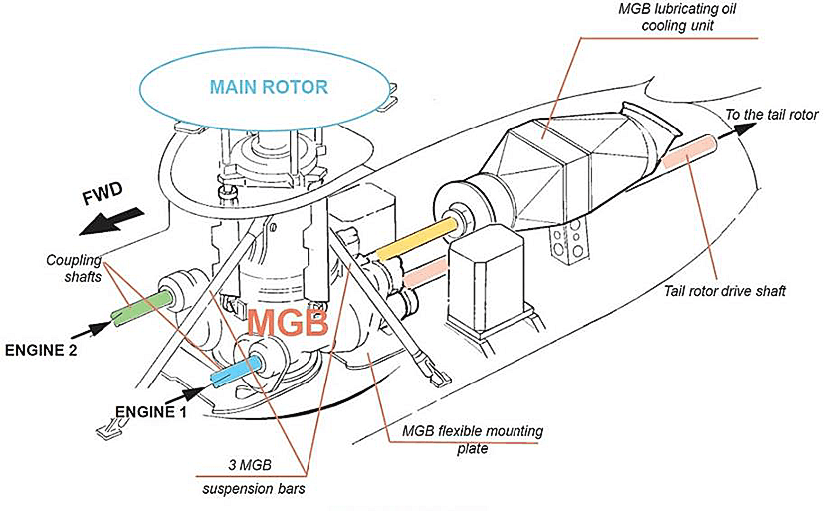

The accident helicopter had two Safran Makila 2A1 engines, with each engine power turbine connected by a high-speed shaft to the MGB, which had two main sections — the lower section or main module, and the upper section or epicyclic reduction gearbox module. Three suspension bars and a flexible mounting plate attached the MGB assembly to the transmission deck/cabin roof (Figure 1).

Figure 1 — Transmission Layout Schematic Diagram

MGB = main rotor gearbox

Source: Airbus Helicopters, Accident Investigation Board Norway

The epicyclic reduction gearbox module (or epicyclic module) on the EC225 LP contains eight first stage planet gears and eight second stage planet gears, each designed as a combined gear and bearing assembly. The gears are manufactured from 16NCD13 steel and subjected to a carburization — case hardening — process designed not only to harden the material but also to help inhibit the growth of fatigue cracks.

Second stage planet gears are considered “critical parts” and can be inspected only after disassembly of the MGB epicyclic module and the gear and bearing, the report said. Other means of monitoring, including MGB chip detection and vibration health monitoring, are used during periods between disassembly. Improved methods of monitoring were implemented after the 2009 crash of an AS332 L2 off the coast of Scotland (“Fractured Gear,” ASW, 2/12). The cause of that crash, which killed all 16 passengers and crew, also was traced to the catastrophic failure of a second stage planet gear in the epicylic module.1

The MGB in the accident helicopter had been damaged in a road accident in Australia and repaired about one year before the crash, the report said. The road accident occurred while the MGB was being transported in a small truck that veered off a gravel road and rolled over when the driver attempted to avoid kangaroos in his path. A subsequent inspection found damage to the external portion of the gearbox but not to internal components.

‘Loud, Sharp and Static’

A review of radio communications and an AIBN interview with the Flesland Approach air traffic controller confirmed that communications with the helicopter had been normal through the last transmission, at 1152:31. After that, disturbances were heard on the radio frequency and were described by the controller and supervisor as “loud, sharp and static.” A “dull metallic noise” was heard from 1153:50 until 1154:22.

The controller called the helicopter several times but received no response, and the helicopter disappeared from radar. At 1156, the crew of a Norwegian Coastal Administration surveillance aircraft that was operating in the area was asked to search for the helicopter; about one minute later, the crew reported seeing smoke. Rescue workers arrived at the scene within six minutes of the crash but “immediately realised that life-saving actions were impossible,” the report said.

Metallurgical Exams

The report said that evidence found in the wreckage, recorded flight data and detailed metallurgical examinations showed that the fatigue crack that led to failure of the second stage planet gear originated in a micro-pit in “the upper outer race of the bearing (inside the second stage planet gear), propagating subsurface towards the gear teeth, where it grew to a complete fracture.”

The failure probably was “initiated by debris caught within the bearing and scratching one or more rollers,” the report added. “This probably caused a band of local work hardening and associated micro-pitting at the outer race.”

The subsequent examination of about 500 second stage planet gears that had been removed from service found indentations and/or micro-pits on almost all of the gears, the report said, adding that the problem “is believed to be due to particle contamination or wear debris inside the main gearboxes.”

The report identified two suppliers — FAG and NTN-SNR — of second stage planet gear bearings for EC225 LP and AS332 L2 helicopters, and noted “dimensional and production differences” between the two.

All eight of the second stage planet gears on the accident helicopter contained bearings were supplied by FAG, and the report said in-service experience had shown that second stage planet gears with bearings from FAG had more spalling events than those with bearings from NTN-SNR.

The accident helicopter’s MGB was subject to condition monitoring through a chip detection system, designed to find and capture “wear debris” or other small particles, and a health and usage monitoring system (HUMS), which analyzed vibration from components of the helicopter’s drivetrain, the report said, adding that all indications were that the chip detection system was working properly and used correctly.

Nevertheless, the report said that the chip detection system was considered 12 percent efficient in detecting particles from the epicyclic module, and the HUMS design was “unable to detect fatigue fractures in second stage planet gears.”

Scotland Accident

The report noted that the 2009 accident in Scotland demonstrated “what could happen to the main rotor when a second stage planet gear fractured as a result of a fatigue crack.” In that case, 36 flight hours before the accident, a magnetic particle was discovered on the epicyclic chip detector, but “due to a misunderstanding or miscommunication, the maintenance task was not carried out and the … main gearbox was not opened,” the report said.

All eight second stage planet gear assemblies in the AS332 L2 that crashed in Scotland in 2009 also were supplied by FAG, the report said, adding that “differences in design and reliability between planet gear bearings supplied by FAG and NTN-SNR were not known to the investigation team and were not considered” during the U.K. Air Accidents Investigation Branch (AAIB) investigation of that event.

“The [Scotland] accident was clearly established to be the result of fatigue failure in a second stage planet gear; however, the post-investigation actions were not sufficient to prevent another main rotor loss,” the report said.

The report added, “The investigation has shown that the combination of material properties, surface treatment, design, operational loading environment and debris gave rise to a failure mode which was not previously anticipated or assessed.”

The AIBN’s safety recommendations, in addition to the call for research into fatigue crack development, said that EASA should revise its certification specifications for large rotorcraft to “introduce requirements for MGB chip detection system performance” and should “develop MGB certification specification to introduce a design requirement that no failure of internal MGB components should lead to a catastrophic failure.”

Noting that its investigation showed that “a critical structural component could fail totally without any pre-detection by the existing monitoring means,” the AIBN also recommended that EASA “research methods for improving the detection of component degradation in helicopter epicyclic planet gear bearings.”

This article is based on AIBN Report SL 2018/04, “Report on the Air Accident Near Turoy, Oygarden Municipality, Hordaland County, Norway; 29 April 2016, With Airbus Helicopters EC 225 LP, LN-OJF, Operated by CHC Helikopter Service AS.” July 2018.

Note

- AAIB. Aircraft Accident Report 2/2011, “Report on the Accident to Aerospatiale (Eurocopter) AS332 L2 Super Puma, Registration G-REDL, 11 nm NE of Peterhead, Scotland, on 1 April 2009.”

Featured image: Accident Investigation Board Norway

Rim fracture: Accident Investigation Board Norway

Flight path: map, © NordNordWest | Wikimedia CC-BY-SA 3.0; modified by Susan Reed with information from Accident Investigation Board Norway

Accident location photo: National Bureau of Crime Investigation (Norway), Accident Investigation Board Norway

First stage planet gears: Accident Investigation Board Norway