An informal review of runway veer-offs — side excursions — in conditions of reduced visibility shows that “a disproportionate number” occurred on wider-than-normal runways, especially those without centerline lighting, the Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) says.1

The ATSB’s conclusion was included in its final report on the Dec. 6, 2016, veer-off of a Virgin Australia 737-800 while landing in a nighttime rainstorm at Darwin International Airport. No one was injured in the runway excursion, and minor damage was reported to the airplane.

In its investigation, the ATSB found that the 737, after a scheduled passenger flight from Melbourne, was on approach to Darwin’s Runway 29. Thunderstorms were nearby, and the airplane flew into heavy rain before reaching the runway threshold; the 22,500-hour captain told investigators he had experienced such conditions only once in his career — about 30 years earlier on a flight into Darwin that ended in a hard landing. During this 2016 approach, there was a light crosswind, which increased in strength as the airplane moved over the runway, and “the aircraft drifted right without the flight crew being able to discern the extent of the drift,” the report said.

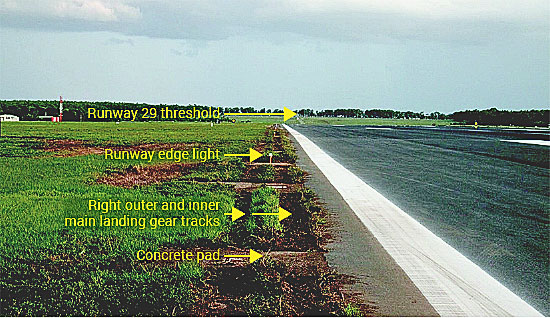

The airplane touched down 21 m (69 ft) to the right of the centerline. Soon afterward, the right main landing gear left the runway surface; it destroyed six runway lights before returning to the runway.

Accident investigators determined that the relatively slight crosswind had nevertheless resulted in a significant deviation from the runway centerline and that visual cues were not adequate to enable the flight crew to detect the deviation and correct it.

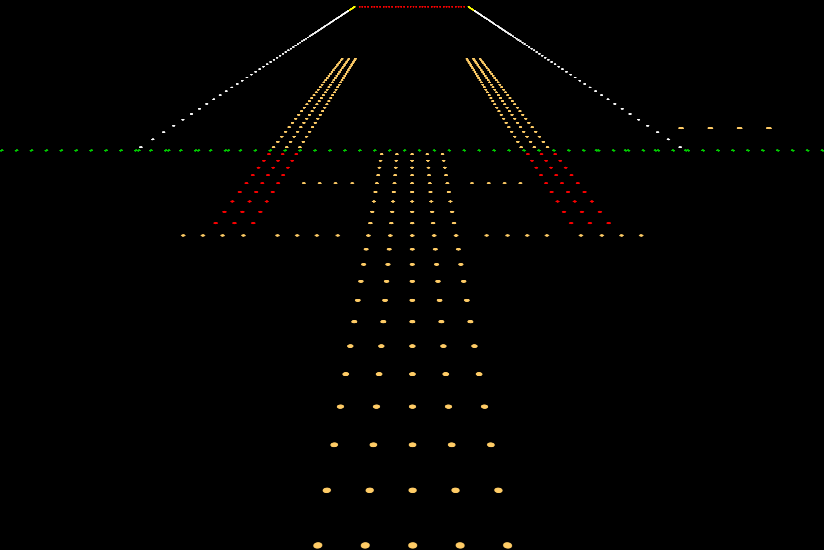

The report said one of the inadequate visual cues was the runway lighting, which did not include centerline lights.

ICAO Guidance

The document noted that the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) says, in Annex 14, Aerodromes, that runway centerline lights and touchdown zone lights shall be provided for runways with a Category II or Category III precision approach. ICAO also recommends that centerline lights be provided for runways with Category I precision approaches, “particularly when the runway is used by aircraft with high landing speeds or where the width between the runway edge lights is greater than 50 m [164 ft].” (Annex 14 does not include a recommendation for touchdown zone lights for Category I runways.)

Additional ICAO guidance included in Document 9157, Aerodrome Design Manual, describes the purpose of centerline lighting: “to provide the pilot with lateral guidance during the flare and landing ground roll or during takeoff.”

The document adds, “In normal circumstances, a pilot can maintain the track of the aircraft within approximately 1 to 2 m [3 to 7 ft] of the runway centreline with the aid of this lighting cue. The guidance information from the centreline is more sensitive than that provided from the pilot’s assessment of the degree of asymmetry between the runway edge lighting. In low-visibility conditions, the use of the centreline is also the best means of providing an adequate segment of lighting for the pilot. The greater distances involved in viewing the runway edge lighting, together with the need for the pilot to look immediately ahead of the aircraft during the ground roll, also contribute to the requirements for a [well-lighted] runway centreline.”

Related Occurrences

ATSB investigators reviewed the bureau’s database and found that between 1997 and 2017, Australian airports reported three veer-offs, including the 2016 Darwin occurrence, that involved an air transport and met a specific set of conditions:

- The airplane lost runway centerline alignment before and during touchdown;

- There had been no difficulty with relevant aircraft or airport equipment that contributed significantly to the veer-off; and,

- The flight crew had experienced no significant problems with height or airspeed stability during the approach.

All three events involved runways without centerline lighting, and two were on Runway 29 at Darwin.

The first event involved another 737 at Darwin on Feb. 19, 2003, also at night and during rain and reduced visibility. In that event, the airplane was at about 200 ft, on the localizer and glideslope, when the captain disengaged the autopilot. Seven seconds later, the airplane began deviating right, and the approach lighting was no longer visible from the cockpit.

The 737 touched down near the right edge of the runway, about 520 m (1,706 ft) from the threshold. The right main landing gear ran off the runway about 590 m beyond the threshold, and the left main gear, about 760 m (2,494 ft) beyond. When the airplane was 1,300 m (4,263 ft) past the threshold, all wheels were back on the runway.

In that case, the report said that the investigation determined that “the flight crew may have encountered an abnormal situation where few reliable visual cues were available for determining the aircraft’s position relative to the centreline of the runway.” Investigators noted the potential for visual illusions during that approach, considering the wide runway, lack of centerline lighting and weather conditions.

The second event, also in 2003, occurred at Emerald Airport in Queensland during the nighttime landing of a Bombardier DHC-8-200 that veered partially off Runway 24 at the end of a nonprecision approach. Heavy rain — and the accompanying sudden, near-zero visibility — left the pilots with virtually no external visual references. The 45-m (148-ft) wide runway had no centerline lights.

The ATSB also identified two related runway occurrences at Darwin — the 2002 runway overrun of a 737, which occurred at night under clear skies, and a 2008 hard landing involving a 717, also at night. The ATSB said the 2002 overrun occurred in an operational environment that was “conducive to visual illusions.” In the case of the 2008 hard landing, the ATSB said the lack of runway centerline lighting limited the available visual cues.

Veer-Offs in Canada

ATSB researchers also examined veer-offs reported in Canada, which has a greater proportion than most countries of runways that are at least 60 m (197 ft) wide.

Seven veer-offs between 1997 and 2017 at Canadian airports met the same criteria used in the Australian review — all occurred at night on 60-m wide runways without centerline lighting. Each event also involved weather-related factors that reduced visibility, the report said. None of the events resulted in injuries; most resulted in damage to the airplanes and all destroyed runway lights or signs, or both.

The report cited 2017 data from civil air navigation service provider Nav Canada, which showed that, of 115 of the country’s busiest airports, 57 percent had runways with no centerline lighting, including 31 percent of airports with runways wider than 50 m and 26 percent of those with runways 50 m wide or narrower.

“It is statistically very unlikely that seven veer-off occurrences in 20 years with similar characteristics took place on these types of runways without any having occurred on the narrower runways or on wider runways with centerline lighting,” the report said.

The document cited the final report by the Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) on a 2017 runway excursion at Toronto Lester B. Pearson International Airport, which reached conclusions similar to those outlined in the ATSB report on the 2016 Darwin event.2

“On runways without centreline lighting, as the distance between runway edge lights increases, it becomes more difficult to judge lateral movement solely by assessing the degree of asymmetry between the runway edge lights — especially when the aircraft is close to the ground and the flight crew’s attention is focused directly ahead of them,” the TSB report said.

“If the distance between runway edge lights is greater than 50 m and runways are not equipped with centreline lighting, there is a risk that visual cues will be insufficient for flight crews to detect lateral drift soon enough to prevent an excursion while operating aircraft at night during periods of reduced visibility.”

Using the same search criteria for the same time period in several other countries, the ATSB identified five veer-off events involving runway misalignment — two in the United States and one each in Finland, Sweden and the Solomon Islands. All five events occurred during nighttime instrument approaches in reduced visibility to runways without centerline lighting. Two were on 60-m wide runways, and three were on 45-m wide runways.

Summarizing all 15 events, the report noted that all occurred in reduced visibility at night on runways without centerline lighting, 11 occurred on runways wider than 50 m, and 13 occurred during a Category I instrument landing system approach.

Earlier Studies

The ATSB also report cited two earlier studies, including a 2009 report by the agency that reviewed 141 runway excursions involving commercial jets from 1998 through 2007. About 40 percent were veer-offs, occurring either on takeoff or landing, and weather was deemed a significant factor in many events. In that report, the ATSB observed that “appropriate lighting of the runway centreline and edges has the potential to provide pilots with better spatial awareness at night or in poor visibility conditions and may reduce the likelihood of veer-offs.”3

A report released by Flight Safety Foundation, also in 2009, said that an examination of 548 runway excursions, including 230 veer-offs after landing, found that runway contaminants were a significant risk factor, as were rain, crosswinds, gusting winds, low visibility and other weather conditions.4

A 2015 report by Airbus said that runway excursions (both veer-offs and overruns) accounted for an increasing proportion of aviation accidents and that the rate of runway excursion accidents had not changed significantly over the 20 previous years — a period in which many accident types experienced declining accident rates.5

The Airbus report, which contained an examination of 25 reported veer-offs involving Airbus airplanes, found three primary environmental factors — a wet or contaminated runway, turbulence or a crosswind, and reduced visibility — were often associated with the events. Nineteen of the 25 veer-offs involved at least two of the three factors, the report said.

Recommendations

As a result of its investigation, the ATSB recommended that ICAO review the provisions of Annex 14 that recommend, but do not mandate, the installation of centerline lighting on Category I precision approach runways wider than 50 m.

The ATSB also recommended that Darwin International Airport “address the risk of very limited visual cues for maintaining runway alignment during night landings in reduced visibility that arise from the combination of the absence of centreline lighting and the 60-m width of Runway 11/29.”

After the event, Virgin Australia began providing additional guidance to flight crews for the approach to Darwin, including notes about the runway width and lighting; and the En Route Supplement Australia, which publishes aeronautical information, incorporated new material about runway lighting and the possible loss of visual references during reduced visibility at Darwin.

Notes

- ATSB. Aviation Occurrence Investigation AO-2016-166, “Runway Excursion Involving Boeing 737, VH-VUI.” Dec. 6, 2016. Adopted May 2019.

- TSB. Investigation A17O0025, “Runway Excursion; Air Canada, Airbus Industrie A320-211, C-FDRP; Toronto/Lester B. Pearson International Airport, Ontario; 25 February 2017.” April 23, 2018.

- Safety Management Specialties. “Report on the Design and Analysis of a Runway Excursion Database.” A special report prepared for Flight Safety Foundation. May 26, 2009.

- ATSB. Aviation Research and Analysis Report AR-2008-018 (1), Runway Excursions, Part 1: A Worldwide Review of Commercial Jet Aircraft Runway Excursions. 2009.

- Airbus SAS. “Lateral Runway Excursions Upon Landing: A Growing Safety Concern?” Safety First Volume 20.

Featured image: © aarrows | VectorStock

Darwin International Airport runway edge: Australian Transport Safety Bureau

Landing at Zürich International Airport: Hansueli Krapf | Wikimedia CC-BY-SA 3.0