The pilot of a Bell 206L-3 was talking on his cell phone during a flight that ended when the helicopter slammed into ranchland near Ancho, New Mexico, U.S., on Sept. 16, 2017, killing the pilot and destroying the helicopter, the U.S. National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) says.

The NTSB said, in a report issued in July, that the probable cause of the accident was the pilot’s distraction by his cell phone during the low-altitude flight.1

The accident was one of several in recent years to be attributed to pilot distraction by a cell phone, laptop computer or other electronic device, and the NTSB has singled out distraction, not only in aviation but also in all other forms of transportation, as one of the areas in which it most wants to see corrective action.

In the case of the Bell 206, the day before the accident, the helicopter, registered to LIN Television in Providence, Rhode Island, U.S., and operated by television station KRQE² in Albuquerque, New Mexico, had been flown to Roswell International Air Center so that the pilot/reporter could cover a news story in nearby Carlsbad. The accident occurred during the return to Albuquerque International Sunport.

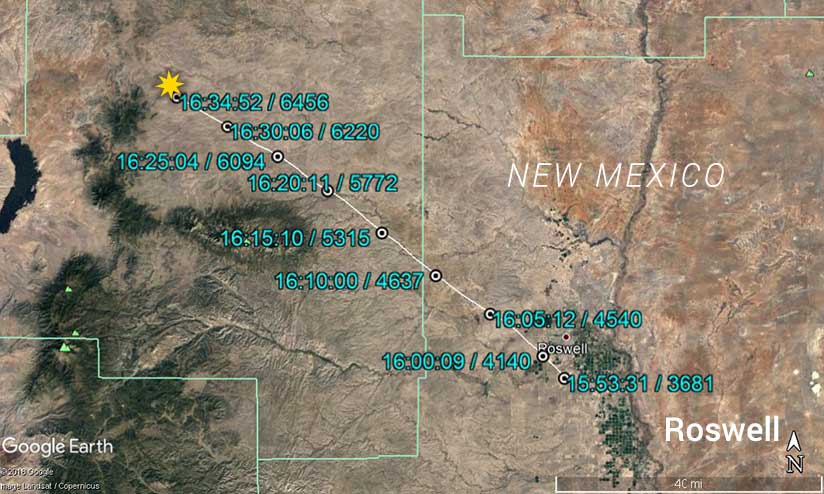

Visual meteorological conditions prevailed for the flight, which began about 1554 local time in Roswell. Terrain beneath the route of flight was between 6,000 ft and 6,400 ft above mean sea level, and data from the helicopter’s GPS showed that in the last five minutes of the flight, the helicopter’s altitude varied between 6,200 ft and 6,456 ft. Accident investigators estimated that the crash occurred around 1635.

A person who had been near the accident site at the time told investigators that he saw smoke coming from a nearby ranch, drove in that direction, found the wreckage and notified local law enforcement authorities.

8,800-Hour Pilot

The commercial pilot had airplane single-engine and multi-engine land and instrument ratings, a commercial rotorcraft certificate with a helicopter rating, and a helicopter flight instructor certificate. He had accumulated a total of 8,800 flight hours. He also held a remote pilot certificate.

The helicopter was maintained in accordance with the manufacturer’s maintenance inspection program, and the last inspection was completed in June 2017. At the time, the helicopter had accumulated 8,799 flight hours, and the engine, 7,956 flight hours and 7,623 cycles. There was no indication that the helicopter was experiencing any pre-impact mechanical problems.

The closest automated weather observation station was at the airport in Roswell, 69 nm (128 km) east-southeast of the accident site. The station’s 1551 weather observations reported a partly cloudy sky, visibility of 10 mi (16 km) and wind from the northeast at 3 mph.

In Albuquerque, 80 nm (148 km) northwest of the accident site, weather conditions at 1552 were similar, including a partly cloudy sky, 10 mi visibility and wind from the east-southeast at 9 mph.

The pilot’s cell phone was found at the accident site and a review of phone records showed that at 1612, the pilot had called a car rental agency.

The rental agent who had talked with the pilot told an inspector from the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) that she “remembered the call well, and that she knew the pilot, because he often rented a car from the agency,” the accident report said. “She added that she could not tell that he was in a helicopter but that he seemed ‘busy or distracted’ and that, as they were talking about a … rental [later that day] and she was ‘mid-sentence,’ the line was disconnected.”

The report concluded that, “based on the available information,” the pilot probably had been using his cell phone when he became distracted. The crash followed, the report said.

Growing Problem

In its current Most Wanted List of Transportation Safety Improvements, the NTSB cites distraction as “a growing and life-threatening problem.”3

“The increasing prevalence of personal electronic devices (PEDs), such as cell phones and tablets, in aviation operations has only expanded the potential ways pilots and other aviation safety–critical personnel can become distracted,” the NTSB said. “When pilots or other aviation safety–critical personnel introduce nonessential distractions, such as PEDs or personal conversations not related to work, into the cockpit or onto the tarmac, the risk to public safety increases exponentially.”

The agency noted that although general aviation pilots are more likely to be involved in distraction-related accidents — partly because they are not subject to the sterile cockpit rule, which prohibits commercial pilots from engaging in distracting personal activities during critical phases of flight — commercial pilots have not always escaped distraction.

Examining Work Schedules

One of the more publicized distraction events occurred Oct. 21, 2009, when the flight crew of Northwest Airlines Flight 188 became so engrossed in searching their personal laptop computers for information on crew scheduling issues associated with the merger of Northwest with Delta Air Lines that, for more than an hour, they did not respond to repeated radio calls from air traffic control (ATC).4 As a result, they flew their Airbus A320 past the intended destination of Minneapolis, Minnesota; they then contacted ATC, turned the flight around and conducted a late but otherwise uneventful landing in Minneapolis.

No one was injured as a result of the overflight, and the A320 was not damaged. The NTSB cited as the probable cause “the flight crew’s failure to monitor the airplane’s radio and instruments and the progress of the flight after becoming distracted by conversations and activities unrelated to the operation of the flight.”

Personal Texting

The NTSB cited a similar contributing factor in the case of an Air Methods Eurocopter AS350 B2 emergency medical services flight that crashed because of fuel exhaustion on Aug. 26, 2011, in Mosby, Missouri, killing the pilot, two medical crewmembers and the patient (“Crackdown on Distraction,” ASW 7/13).5

The NTSB said that the pilot had failed to confirm before his first takeoff that the helicopter had adequate fuel to complete the multi-leg flight. The agency cited that failure as one element of the probable cause of the accident, along with the pilot’s “improper decision” to begin the next leg of the flight after becoming aware that the fuel level was critically low. Among the contributing factors was “the pilot’s distracted attention due to personal texting during safety-critical ground and flight operations.”

The texting occurred “while flying, while the helicopter was being prepared for a return to service and during his telephone call to the communication specialist when making his decision to continue the mission,” the NTSB said in its final report on the accident. The report characterized the texting as “a self-induced distraction that took his attention away from his primary responsibility to ensure safe flight operations.”

The report said that an examination of the pilot’s cell phone records showed that he had sent and received text messages and phone calls throughout the day. Although there was no indication that the pilot was texting when the accident occurred, his texting during the flight violated the company’s policies on cell phone use, the report said.

“There is no evidence that the pilot’s airborne texting activities directly affected his response to the engine failure,” the document added. “However, the personal texting activities would have periodically diverted the pilot’s attention from flight operations and aeronautical decision making.”

No Multitasking

The NTSB said in its Most Wanted list discussion that the presence in the general aviation cockpit of personal electronic devices has introduced challenges to the see-and-avoid concept. Conceding that aviation applications on personal electronic devices can be useful, the NTSB noted that they also result in “more head-down time, limiting a pilot’s ability to see other aircraft.” In some cases, the presence of electronic devices has led to midair collisions involving general aviation aircraft, the NTSB noted.

“Distraction must be managed — even engineered out — to ensure safe operations,” the NTSB said. “A cultural change is needed for all aviation personnel to understand that their safety and the safety of others depends on disconnecting from deadly distractions.”

The NTSB recommended that nonoperational use of personal electronic devices should be banned in aircraft operating under U.S. Federal Aviation Regulations Part 91 (general operations) and Part 135 (commuter and on-demand operations).

In addition, the industry should develop strategies to help pilots identify and avoid distractions while directing their attention to “operationally relevant information to maintain flight safety.” Procedures also should be in place for other safety-critical personnel, the NTSB said.

The agency added that commercial pilots should comply with the FAA’s sterile cockpit rule, and that other pilots should “voluntarily reduce and manage distractions to maximize attention.”

Notes

- NTSB. Accident report no. CEN17FA355. Sept. 16, 2017.

- The television station’s call letters were mis-stated in the accident report. KRQE is correct.

- NTSB. Most Wanted List of Transportation Safety Improvements, 2019–2020.

- NTSB. Accident report no. DCA10IA001. Oct. 21, 2009.

- NTSB. AAR-13-02, Crash Following Loss of Engine Power Due to Fuel Exhaustion; Air Methods Corporation; Eurocopter AS350 B2, N352LN; Near Mosby, Missouri; August 26, 2011. Adopted April 9, 2013.

Featured image: © VanderWolfImages | Dreamstime.com

Helicopter accident site and flight path: U.S. National Transportation Safety Board

Phone with text messages: © art-sonik365 | VectorStock, modified by Susan Reed