Best practices within safety management systems (SMS), as implemented for international commercial air transport by the aviation industry and governments, often share a common characteristic, subject matter experts say. Analyzing high volumes of safety data from flight operations and identifying risks are only part of the equation. The information derived from the process also must become integral intelligence in order for an SMS to create, implement and validate the effectiveness of risk mitigations, the experts told the FSF 68th annual International Air Safety Summit (IASS).

Several presenters at IASS, held in November in Miami Beach, Florida, U.S., emphasized that a growing number of industry/government organizations have turned initially far-reaching, high-level aspirations for SMS — as introduced in Canada about 10 years ago — into everyday capabilities that make a measurable difference, and that the trend is continuing.

Delving Deeper in Canada

A current characteristic of a mature SMS is combining proactive/predictive processes that help identify and mitigate hazards with reactive processes to learn safety lessons from accidents and incidents. Even with those processes established, an “SMS can’t be expected to predict and deal with every possible occurrence in advance,” said Kathy Fox, chair, Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB). “When you get right down to it, many — if not most — accidents can be attributed to a breakdown in the way the organization proactively has identified and mitigated hazards and managed risks. [Airline SMS managers now] look at the way that hazards are not just identified but how they are reported to senior management, then how those reports are received and actioned because all of these are things that can have a tremendous impact on the operating context of an occurrence.”

As an example of operator SMS performance issues, she recounted a 2011 Boeing 737 NG takeoff incident,1 in which the flight crew’s effective response to erroneous air data indications resulted in no damage or injuries but they downplayed the potential risk of loss of control–in flight. Investigation by TSB — which became aware of the event only because the flight crew had reported the overweight landing as required — found inadequate consideration by the operator’s SMS. The airplane manufacturer’s prior advice to operators of the aircraft type had been disregarded by this operator, and the operator deemed the event too insignificant to be reportable to TSB or to be fully investigated internally.

Fox said, “This was an example of what some researchers call a ‘weak signal.’ Even though Boeing was pointing out that such events were occurring more frequently than predicted, the operator — Sunwing [Airlines] — did not consider the notice as a statement of hazard that should be analyzed by a proactive process. Therefore, the advisory was not circulated widely within the company or to flight crews. … Following the occurrence, the operator still did not see any hazards worthy of analysis via SMS, at least initially. The effective performance of the crew masked the [broader issue that] this, in flight, could potentially have serious consequences.”

Decision makers within organizations have to ensure that their SMS incorporates a mindful infrastructure, she said, adding, “This involves tracking small failures, resisting oversimplification, taking advantage of shifting locations of expertise in organizations and listening for and heeding those weak signals.”

She counts among key factors indicating a strong SMS and safety culture: congruence between tasks and resources, effective and free-flowing communication, clear grasp of what is at stake, and keeping a learning orientation. She added that a robust SMS is “exactly about putting in place a formal process to recognize hazards, to analyze them and to implement mitigating measures to reduce the risk that they hold … not just from the top down but also from the bottom up.

“Even the most robust SMS is subject to the same pressures that can affect any other corporate initiative, [such as] corporate attitudes, the level of commitment from senior management, competing priorities, finite budgets, etc. … In the case of the takeoff I described, the operator had an SMS, but hazards weren’t initially recognized as worthy of analysis. … TSB is not blaming this operator. Unfortunately, this happens more often than we’d like.”

In comparable cases, TSB found managers of airline SMSs to be incapable, unwilling or ineffective at identifying risk and/or dealing with the implications of safety intelligence, she said, citing reasons such as relatively low experience applying SMS concepts or that “an SMS may be something put in place only grudgingly to comply with legislation, in which case, it may exist on paper but not at all in day-to-day operations.”

FAA Compliance Philosophy

SMS concepts also began to profoundly influence government safety oversight in the United States about 10 years ago, according to John Allen, vice president, safety, JetBlue Airways, and former director, Flight Standards Service, U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). He said that early discussions made clear that, for mutual credibility in working with the aviation industry, SMS would have to be adopted by the regulator as well as the regulated. Industry-government transparency also would be necessary for SMS to succeed. He called this “a collaborative effort between the FAA and the airline industry to share data, to analyze risk, to come up with mitigating actions to move forward.”

He said that a “pragmatic” director of safety at the time expressed doubts that FAA principal operations inspectors could be reoriented after decades of using safety data to hand down enforcement packages against airlines. “That resonated with me,” Allen said, recalling thought processes that ultimately led current FAA Administrator Michael Huerta to announce a compliance philosophy (FAA Order 8000.373) and to issue an updated compliance and enforcement guide for all FAA inspectors (ASW, 11/15).

“We really wanted to look at things that were at highest risk but we couldn’t because we knew that we had to fix how we, as inspectors, would address these things because there weren’t enough of us,” he said. “We were getting diminishing budgets … but we, as inspectors, felt that the way the compliance and enforcement guide was written, we had to use enforcement as the first course of action … not realizing that it really hurts safety.”

The new documents essentially have formalized mutual responsibility by the FAA and airlines to accommodate the philosophy for the sake of the future of aviation safety, he said. “Under SMS, we’re looking for the highest level of safety, to go above and beyond the basic regulatory compliance,” Allen said. “Regulatory compliance is a given, we’re expected to go higher … to foster that open and transparent exchange of data. … There has to be a close partnership.”

FAA inspectors had needed clarity about their options to use such alternative responses to correct unintentional deviations or noncompliance caused by factors such as flaws in systems and procedures, simple mistakes, lack of understanding or diminished skills. “That is going to help [airlines] tremendously in the future for SMS. That is going to move our sophistication [to] the new era of safety [going] forward,” Allen said.

State-Level SMS Advances

SMS at the state level does not mean a state will take ownership of the risk away from the industry, said Hazel Courteney, head of strategy and safety assurance, U.K. Civil Aviation Authority (CAA). “A national authority is talking to its stakeholders. It’s gathering data from all its stakeholders and so is actually uniquely placed to be able to see what the data are telling us, what the patterns are, and what the big picture is. [It] is uniquely placed to drive and coordinate some safety improvements before that [situation] ends in an accident. … This is really a macro, overarching level of safety management.”

The current source of global guidance for state safety programs (SSPs) and related oversight activities is International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) Annex 19, Safety Management.2 “Right now, there is a quite complex amendment going through the ICAO system … adding to [SSP] safety risk management at the state level, continuous improvement measured by safety performance data and emergency response planning,” she said. “These kinds of regulations might be scalable for states in different situations.”

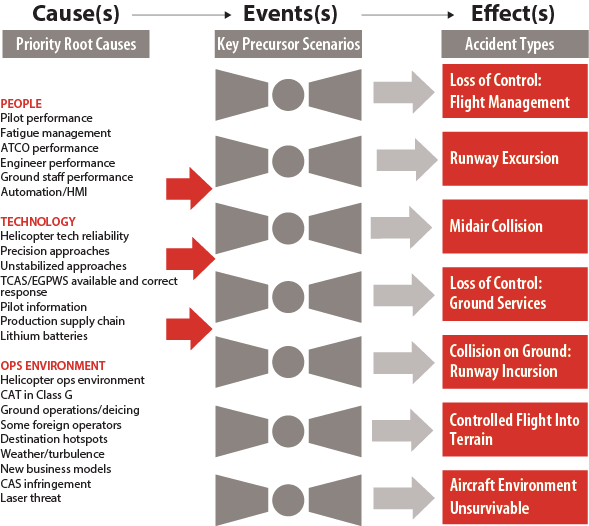

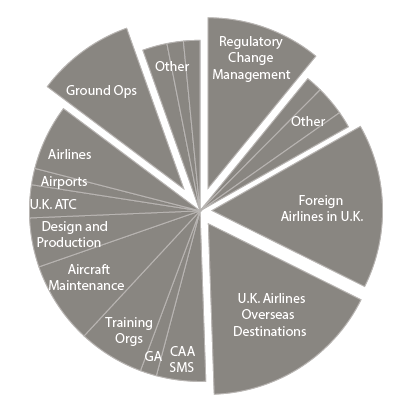

The SMS of the U.K. CAA has some characteristics and documents comparable with those of other states, as well as a unique general safety model that has applied bowtie analysis (Figure 1; ASW, 6/13) to generate its Significant Seven risk-reduction priorities, and the Safety Wheel (Figure 2), plus about 14 bowtie analyses of other important issues.

Figure 1 — SMS Bowtie Analyses Reveal Significant Seven U.K. Safety Issues

ATCO = air traffic control officer; CAS = controlled airspace; CAT = clear air turbulence; EGPWS = enhanced ground-proximity warning system; HMI = human-machine interface; OPS = operations; SMS = safety management system; TCAS = traffic-alert and collision avoidance system; tech = technical

Notes: The U.K. Civil Aviation Authority SMS has conducted bowtie analyses of flight operations risk factors, assessing priority root causes in key precursor scenarios to choose its Significant Seven national safety priorities.

Source: U.K. Civil Aviation Authority

“The Safety Wheel came about because we talked about developing the SSP … and we decided that what it should do is to protect U.K. citizens from flight safety risks. … When we put the U.K. citizen in the center of our thinking — and put around them [the question] ‘Where does risk exposure to that individual come from?’ — what we discovered is that a lot of it comes from sources where we have no oversight,” Courteney said. “In some cases, we have no influence or even any relationship. … [This insight] did get us thinking that perhaps where we see hotspots — events in particular locations or groups of events for particular airlines coming into our airspace — we should be a bit more proactive in addressing that.” The first effort was to meet, propose a safety partnership and collaborate with U.K. CAA counterparts from Turkey.

Figure 2 — Safety Wheel: Sources of Risk to U.K. Citizens

ATC = air traffic control; CAA = U.K. Civil Aviation Authority; GA = general aviation; Ops = operations; Orgs = organizations; SMS = safety management system; U.K. = United Kingdom

Notes: A strategic planning exercise of the U.K. CAA SMS was to visualize a citizen–air traveler at the center of risk factors, then prioritize relevant risk mitigations.

Source: U.K. Civil Aviation Authority

“We all walked away from that with a lot of new insights and quite a lot of actions. In three months, [safety] events were down 85 percent. By the end of a year, they were zero. … The benefit is we understand each other better, and we actually know each other so when things start to happen, we can pick up the phone and sort it out. Since then, we’ve started to work with some other states, and we’ve had some other projects,” she said.The Significant Seven emerged from the SMS as a way to get the maximum safety benefit by identifying leading fatal accident types, and the two or three main scenarios that end in those crashes. “We did bowtie analyses on those scenarios … and they really guided us to where our safety initiatives should be,” Courteney said.

Ten years ago, there were no ICAO requirements for states to implement an SMS or an equivalent concept, added co-presenter Amer Younossi, deputy division manager, FAA Safety Management and Research Planning Division.

The United States has had various SMS-relevant notices and policies in place for about a decade, affecting various levels of civil and military aviation, he said. “The secretary of transportation put out a document encouraging all the modes to implement internal safety management systems. … [The FAA introduced] multiple activities, multiple layers that address safety management for us. At the highest level for us is the U.S. [SSP, completed in January 2015], which essentially documents how we manage safety within the United States. It provides the framework for us. The next level below that is the FAA SMS. It actually is very similar to an SMS for a service provider.”

The current SSP contains regulations specifying the SMS requirements for the companies operating under Federal Aviation Regulations Part 121, Air Carrier Certification; for the FAA Air Traffic Organization; and refers to the SMS rulemaking under way for aircraft design and manufacturing organizations and airports. Voluntary adoption of SMS by other industry sectors is expected. “That’s the area that we’re not fully compliant with [ICAO standards],” Younossi said. A related FAA strategic initiative calls for risk-based decision making “to ensure that we are moving to a safety management construct,” he said.

Ground-Level SMS

By harnessing efficiencies gained in SMS data automation and merging cross-functionality trends into a centralized safety database, airline safety departments can better analyze what is happening over time and strategically target their mitigations, said Christopher SanGiovanni, director ground safety, JetBlue Airways.

“[We’ve] moved to a single data stream and a common causal taxonomy over the last several years,” he said. “[The SMS determines how we’re] currently turning data into information by using automated outputs on what we call live dashboards, and … we are already seeing benefits of targeted mitigation.”

Consolidating safety data streams quickly led to the discovery of different risk “languages” being spoken by different departments. “We could not trend causation, for example, across an internal evaluation … because we were using different languages to categorize our findings and even different methodologies. … So we therefore developed the JetBlue safety event taxonomy. Simply put, it’s a language to identify causal factors that span organizational findings [and based on the industry-standard human factors analysis and classification system (HFACS)]. [It’s] systemic in nature as well as [applicable to] individual errors and failures.”

With the HFACS framework of causal factors, the SMS can compare one accident with another or even compare events that seem impossibly dissimilar, such as comparing cases of pilots entering the wrong information into the flight management system and ramp personnel incorrectly loading cargo.

“With HFACS, these two events can be compared not only by the psychological origins of the unsafe act, but also by the latent conditions within the organization that allowed these acts to happen. … Common trends within an organization can be identified,” he said. JetBlue has optimized use of descriptors within the framework, creating a still finer classification called nano codes.

“With hundreds of nano codes now identified … we are able to trend across the different safety and quality programs in a very JetBlue-specific way,” SanGiovanni said. “This analysis and categorization feeds our SMS management structure. Systemic risk that develops a notable trend is identified through investigation, evaluations [or] even our [voluntary] safety-concern reporting.

“Then it enters the system from the bottom and flows up the SMS structure until the risk is accepted or mitigated at an acceptable level at the specific level of the organization with authority to do so. … The automated data dashboards allow for constant live, up-to-date key performance indicators and trend monitoring — facilitating senior leadership engagement and addressing their thirst for data [and enabling them to drill down with a few mouse clicks into associated precondition nano codes]. … This automation of the data is our foundation for future advanced analysis, such as data modeling, [and] ultimately forecasting, predictive software and text mining. … The targeted mitigations and the data visualization are already allowing us to see how effective the mitigation is over time. Targeted mitigation is our underlying philosophy [because] we have limited resources; we cannot tackle head-on every issue that data identify. [We] must be selective and productive with our mitigation and use a risk-based approach.”

Notes

- TSB. “Erroneous Air Data Indications, Sunwing Airlines Inc., Boeing 737-8Q8, C-FTAH, Toronto–Lester B. Pearson International Airport, Toronto, Ontario [Canada], 13 March 2011.” Aviation Investigation Report Number A11O0031. The report said that discrepancies between the Sunwing SMS manual and company practices at the time of the event included a hazard analysis procedure not practiced, an investigation procedure that did not detail how to conduct investigations, and lack of training on safety-event follow-up responsibilities of safety coordinators. Transport Canada subsequently accepted the airline’s corrective action plan, TSB said.

- ICAO. Annex 19, Safety Management. First Edition, Nov. 14, 2013. Annex 19 is supported by Doc 9859, Safety Management Manual, Third Edition, May 3, 2013.

Featured image: © Mathieu Pouliot | AirTeamImages

jetBlue ground operations: © JetBlue Airways (image from ramp operations safety video)