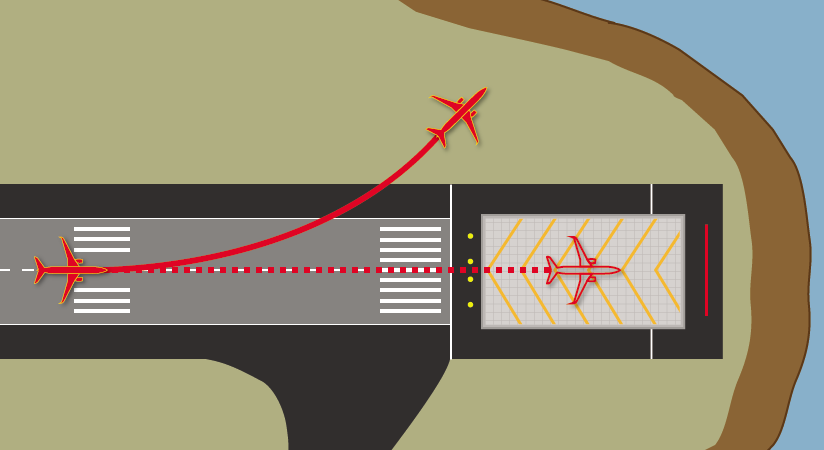

Pilots involved in two recent runway overruns have veered off the landing runway and onto adjacent grass, for the most part avoiding the engineered materials arresting system (EMAS) designed to safely halt an overrun.

Representatives of the industry and the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) told a safety conference held by the Air Line Pilots Association, International (ALPA) in Washington in late July that intentional avoidance of EMAS — a crushable concrete installation placed at the end of a runway — has figured in only a small number of events, and that they cannot explain why it has happened.

“There’s a myth that if you take the dirt, you won’t be on the news,” said FAA Runway Safety Group Manager James Fee.

Capt. Greg Wooley, vice president of flight operations for ExpressJet, agreed, adding that some may also believe that the grass and dirt in an off-runway rollout might help stop the airplane.

One recent event involved an Eastern Air Lines Boeing 737-700 charter flight that overran Runway 22 while landing at LaGuardia Airport in New York City on Oct. 27, 2016, traveling through a corner of the EMAS before coming to a stop to the right of the EMAS area and 172 ft beyond the runway’s end.1 Although the 737 passed through only a corner of the EMAS, the encounter nevertheless helped slow the airplane. The 20,638-hour captain told accident investigators that he had forgotten that there was an EMAS at the end of the runway. The flight was transporting Mike Pence during his successful vice presidential campaign; neither Pence nor any of the 47 other passengers and crew were injured.

The U.S. National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) is continuing its investigation of the event, but, in a summary of flight crew interviews included in the docket that accompanied the preliminary and factual reports on the event, the board noted that the captain had “said that he thought he would get better braking veering to the right, and had forgotten about the EMAS. He said he was looking for the most drag at the end.”

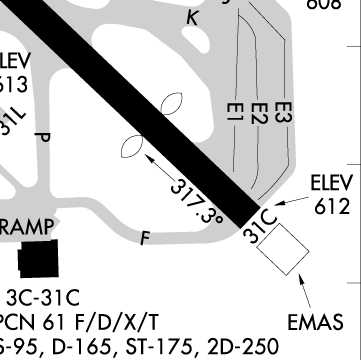

In the second event, on July 12, 2017, a HondaJet carrying six people ran off the departure end of Runway 31C at Chicago Midway Airport and onto wet grass to the left of the EMAS. Official reports on the event were not available, but news reports said the airplane came to a stop just before an airport fence.2 According to those reports, no one in the airplane was injured. The overrun was near the site of a Dec. 5, 2005, overrun accident that killed a passenger in a vehicle on a highway just the other side of an airport perimeter fence.3

Participants in the ALPA conference recommended action to increase pilot awareness of EMAS capabilities.

The FAA is developing signage to inform pilots if they are on a runway with an EMAS. Such signs could enhance pilots’ situational awareness, Kahlil Kodsi, manager, FAA Airport Engineering Division, AAS-100, told the conference.

Flight crews sometimes don’t mention EMAS in approach and landing briefings — an omission that Wooley said should be corrected, noting that although the first EMAS installations were accomplished about two decades ago, they have become more common in recent years.

“The more information a flight crew has, the better,” Fee added, noting that the decision to proceed onto an EMAS is “essentially reflexive.”

‘I Was Fighting You’

The NTSB report on the LaGuardia incident noted that the flight had begun in Fort Dodge, Iowa, in late afternoon, and as it neared LaGuardia, night instrument meteorological conditions prevailed, including 3 mi (5 km) visibility in rain. The 737 was above the glideslope in the latter part of the instrument landing system (ILS) approach to Runway 22 and touched down at 1941 local time, about 4,242 ft (1,294 m) beyond the threshold of the 7,001-ft (2,135-m) runway.

About 4.5 seconds after the main landing gear touched down (and the 737 had traveled 1,250 ft [381 m] farther down the runway), the captain deployed the speed brakes; maximum reverse thrust was commanded 3.5 seconds later, after the airplane had traveled 5,892 ft (1,797 m) beyond the threshold. The report said the captain told accident investigators that, as he saw the end of the runway approaching, he applied maximum braking and right rudder.

The captain also told investigators that, although “he said he vaguely remembers reading about EMAS, [he] has not had any training on it.”

In his written statement to the NTSB, the captain said that, during the landing roll, he “recognized that we were not decelerating fast enough, and I instinctively applied maximum manual braking. Just prior to the EMAS, I pushed the right rudder pedal, steering the airplane to the right into the grass.” NTSB documents said that he told investigators that he was trying “to avoid the road he perceived at the end of the runway.”

The cockpit voice recorder transcript said that, after the airplane had come to a stop, the captain said, “I should have gone straight ahead and we would have been fine,” and the first officer responded, “Yeah, I was … fighting you. Because I was trying to stay on the centerline.”

Later, the first officer told investigators that he “was trying hard keep the airplane on the centerline” by applying left brake and rudder. He said that he had “heard about EMAS” but had no formal training on what to do when encountering it.

In an interview with investigators, Eastern’s chief pilot said that the airline had not included EMAS in pilot training but planned to “incorporate what it does and what it is there for into future training.” The NTSB’s factual report said that in the aftermath of the incident, Eastern added EMAS training to its pilot training program.

67 Airports

EMAS arrestor beds — developed in 1986 by Engineered Arresting Systems Corp. (ESCO), working with the FAA, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey and the University of Dayton — have been installed at the ends of 107 runways4 at 67 airports in the United States; 10 additional EMAS projects are expected to be completed this year or in 2018 at seven airports, according to the FAA.

A standard EMAS arrestor bed is capable of stopping an airplane traveling about 80 mph (129 kph), the FAA said, but even shorter-than-standard arrestor beds can slow or even stop an airplane overrun.

The FAA said that nearly all of today’s EMAS installations are made of ESCO’s EMASMAX, current-generation blocks of crushable cellular cement material. A small number of existing and planned arrestor beds are Runway Safe’s EMAS, foam silica manufactured from recycled glass and contained within plastic mesh that is anchored to the pavement at the end of a runway.

EMAS was an outgrowth of FAA efforts to improve runway safety areas (RSAs), which typically are graded areas that extend 1,000 ft (305 m) beyond the departure end of a runway and are intended to be free of objects that could damage an airplane in case of an overrun. Because some airports were built in areas that lacked suitable land for a 1,000-ft RSA, EMAS was seen as an alternative means of stopping an aircraft that overruns a runway.

The First ‘Save’

Overruns Halted by EMAS

Engineered materials arresting systems (EMAS) at U.S. airports are credited with safely stopping the following 12 runway overruns of airplanes carrying a total of 282 passengers and crew, according to the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration:

- A Saab 340 at Kennedy International Airport in New York in May 1999;

- A McDonnell-Douglas MD-11 at Kennedy International Airport in May 2003;

- A Boeing 747 at Kennedy International Airport in January 2005;

- A Mystere Falcon 900 at Greenville (South Carolina) Downtown Airport in July 2006;

- An Airbus A320 at Chicago O’Hare Airport in July 2008;

- A Bombardier CRJ-200 at Yeager Airport in Charleston, West Virginia, in January 2010;

- A Gulfstream G-4 at Teterboro (New Jersey) Airport in October 2010;

- A Cessna Citation II at Key West (Florida) International Airport in November 2011;

- A Cessna 680 Citation at Palm Beach (Florida) International Airport in October 2013;

- A Falcon 20 at Chicago Executive Airport in January 2016;

- A 737 at LaGuardia Airport in New York in October 2016; and,

- A Cessna 500 Citation at Burbank (California) Airport in April 2017.

The first EMAS was installed in 1996 at Kennedy International Airport in New York, which also was the scene of the first EMAS “save” — a Saab 340’s runway overrun on May 8, 1999.5

According to the NTSB’s final report, that accident followed an ILS approach to Runway 4R that was conducted “with excessive altitude, airspeed and rate of descent” and with the airplane above the glide slope. The airplane landed 7,000 ft (2 km) beyond the approach end of the runway and overran the departure end.

“The airplane traveled off the end of the runway, over a deflector, and onto an … EMAS,” the NTSB report said. “The airplane traveled approximately 248 feet [76 m] across the 400-foot [122-m]–long EMAS, and the landing gear sank approximately 30 inches [76 cm] into the EMAS, at its final resting place.”

One passenger suffered a broken leg while evacuating the airplane; the other 29 passengers and crew were uninjured. The airplane received substantial damage.

If the EMAS had not been installed, the report said, “it is reasonable to assume that … the airplane would have traveled 500 to 1,000 feet [153 to 305 m] beyond the end of Runway 4R before coming to rest.”

Within the 500 ft beyond the runway’s end was “a shallow, mud-based estuary, with its bottom about 10 to 15 ft [3 to 5 m] below the runway level,” that had been the scene of a 1984 runway overrun that left 12 people injured and the airplane substantially damaged, the report said. That accident had prompted a 1987 NTSB safety recommendation calling on the FAA to begin research into the feasibility of “soft-ground aircraft arresting systems.”

The second and third EMAS saves also occurred at Kennedy, but they were followed by nine additional occurrences at nine other airports in which EMAS installations safely stopped runway overruns, the FAA said (See “Overruns Halted by EMAS”).

Notes

- NTSB. Aviation Incident Factual Report, Incident No. DCA17IA020, and accompanying docket material. Oct. 27, 2016.

- News reports, including: Laboda, Amy. “First In-Service HondaJet Incident: Overrun at MDW.” AinOnline, July 17, 2017.

- NTSB. Accident Report NTSB/AAR-07/06, Runway Overrun and Collision; Southwest Airlines Flight 1248; Boeing 737-7H4, N471WN; Chicago Midway International Airport, Chicago, Illinois; December 8, 2005.

- All but one of the 107 EMAS arrestor beds were installed by ESCO; the other was installed by Runway Safe EMAS.

- NTSB. Aviation Accident Final Report, Accident No. NYC99FA110. May 8, 1999. The report said the probable cause of the accident was the pilot-in-command’s (PIC’s) failure to perform a missed approach. Cited as contributing factors were his “improper in-flight decisions, … failure to comply with FAA regulations and company procedures, inadequate crew coordination and fatigue.”

Featured image: © Zodiac Aerospace, modified by Susan Reed

Chicago Midway Airport diagram and Teterboro Airport: U.S. Federal Aviation Administration