Safety management systems (SMSs) within airlines and maintenance and repair organizations (MROs) have advanced rapidly in the past decade. Conceived by the International Civil Aviation Organization and gradually being put into practice through regulation by national aviation authorities, SMSs soon will be required for airlines around the world. For example, the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) mandates that all U.S. commercial airlines (Part 121) implement an SMS by Jan. 8, 2018. One major component of an SMS is risk management, which requires that hazards to safety of flight be identified and assessed for risk, and that unacceptable risk be mitigated to acceptable levels.

International guidance for SMS design recommends three approaches in identifying safety hazards: a reactive approach (the investigation of accidents, incidents and events); a proactive approach (the active identification of safety hazards through the analysis of the organization’s activities, using tools such as mandatory and voluntary reporting systems, safety audits and safety surveys); and a predictive approach (capturing system performance as it happens in real time during normal operations, such as observations of the performance of the aircraft maintenance technicians (AMTs) during a heavy check of a large commercial jet.

As part of its predictive approach, the Airlines for America (A4A) Maintenance and Ramp Human Factors Task Force has extended the line operations safety audit/assessment (LOSA) concept to assess maintenance and ramp (M/R) operations.1 The FAA and A4A also have published separate versions of M/R LOSA implementation guidelines.

Through strictly non-punitive, peer-to-peer observations, maintenance LOSA (MLOSA) takes “snapshots” of normal aircraft maintenance operations and helps the MRO to understand safety-related decisions of ordinary people who are under the influence of normal, everyday pressures. MLOSA incorporates the threat and error management (TEM) conceptual framework, which recognizes that safety threats and errors are likely to occur in all normal operations. Compared with traditional audits conducted by external agencies or by internal safety and quality assurance staff, MLOSA “paints” for the organization a much more realistic picture of what is going on.

In addition to identifying safety threats and errors, MLOSA data can help an organization to estimate — by a sampling process — the occurrence probability; this capability exceeds that of most mandatory and voluntary reporting systems. The predictive capability of MLOSA also can help analysts to discover emerging risks from future operational changes expected inside or outside the organization and its operational environment. Mitigating action therefore can be initiated before the risk actually appears. MLOSA also identifies exemplary AMT behaviors that can be reinforced in training.

Boeing Commercial Aviation Services offers MLOSA support and training to the international airline industry. For example, Boeing supported Air France Industries (AFI) to launch an MLOSA program in November 2014.

Case Study Background

Within AFI, the Flight Operations business unit carried out a LOSA in 2011, and this assessment was considered very successful. AFI subsequently made a commitment to a campaign of recurrent LOSAs for pilots.

In maintenance operations, by mid-2013, AFI recognized the need to complement its existing reactive and proactive safety programs by capturing snapshots of day-to-day performance — i.e., operational difficulties or safety threats in unscheduled or scheduled maintenance — and by developing strategies for dealing with those difficulties or threats. AFI also renewed its commitment to increase the involvement of frontline employees and to further enhance its safety culture.

One expected outcome was to measurably put into practice the slogan “safety is not just for safety professionals within the organization, it’s a responsibility of everyone in the organization.”

AFI leaders presumed that frontline employees are the true experts, and have the best vantage point to observe maintenance operations as they occur and, consequently, to identify the problems and fixes. Maintenance failures are not random. There is a clear need to understand how the safety threats, the latent conditions and the errors committed eventually come together and lead to a reduced safety margin.

Implementation Begins

Assisted by Boeing, AFI launched the MLOSA program after a six-month preparation period and educational campaign by a new project team. Since 2014, work toward full implementation has progressed through three phases for each of the following three AFI business units (Table 1): Line and Base Maintenance (in which base maintenance personnel perform, on average, 275 C-check or D-check inspections for narrow- and wide-body aircraft each year); Component Shops (which support more than 1,300 aircraft worldwide); and Engine Shops (which handle 500 visits and 280 thrust reverser overhauls each year).

|

AMTs = aircraft maintenance technicians Source: Air France Industries (AFI) |

||

| Completed | In Progress | Scheduled |

| 1st quarter 2015 | 2nd quarter 2016 | 3rd quarter 2016 |

| Line and Base Maintenance | Component Shops | Engine shops |

| 1,500 AMTs | 700 AMTs | 600 AMTs |

| 406 observations | ~300 observations | ~250 observations |

Line and Base Maintenance was the focus of Phase 1, completed in the first quarter of 2015. To promote the entire program and generate buy-in, the MLOSA project team attended or conducted more than 90 face-to-face meetings with the frontline employees and union groups. Twenty-six AMTs soon volunteered to become MLOSA observers. They were trained by Boeing during a one-day MLOSA observer training course. The course covered theoretical background, classroom practice and practice observations in hangars.

Based on safety information from event investigations and voluntary reporting by AMTs, the project team selected a number of maintenance tasks as their primary focus within Phase 1, such as wheel/brake change, engine change, landing gear servicing, landing gear removal/installation, flight controls components removal/installation, cabin systems repair, avionics/mechanical systems troubleshooting, and tooling management.

During the following two and a half months, the 26 observers completed 186 observations and compiled 406 observation reports. A total of 1,500 AMTs at Paris Charles de Gaulle Airport (CDG) and Paris Orly Airport (ORY) were involved in this phase. Table 2 summarizes the distribution of the types of observations.

| Type of Observation | Observation Occurrences | Percentage of Total Observations |

| MLOSA = Maintenance Line Operations Safety Audit/Assessment

Source: Air France Industries |

||

| Additional threats and errors | 18 | 4.4% |

| Close-up/complete restore | 25 | 6.2% |

| Install | 67 | 16.5% |

| Installation test | 38 | 9.4% |

| Planning | 43 | 10.6% |

| Prepare for removal | 48 | 11.8% |

| Prepare to install | 43 | 10.6% |

| Removal | 60 | 14.8% |

| Servicing | 48 | 11.8% |

| Troubleshooting | 16 | 3.9% |

| Totals | 406 | 100.0% |

Each MLOSA observer took this task very seriously. The TEM conceptual framework was new to the observers and to those who were observed. The observers soon found that a significant amount of analysis and paperwork were required while they conducted and documented each observation. Once the technicians overcame this step in the learning curve, their work took off and produced highly valuable MLOSA observation reports.

Phase 2 of MLOSA focused on the Component Shops. After four months of preparation, this business unit completed its launch of Phase 2 in the second quarter of 2016. The preparation comprised getting top management and unions involved; selecting and training observers; customizing observation forms; and creating a Microsoft Excel data-entry form suitable for analysis. The resulting Component Shops form includes three new sections titled “Incoming Inspection Check,” “Disassembly” and “Assembly.” Similarly, a corresponding Engine Shops observation form includes three new sections titled “Incoming Check,” “Cleaning and Nondestructive Testing (NDT) Inspection” (Table 3).

|

MLOSA = Maintenance Line Operations Safety Audit/Assessment Source: Air France Industries (AFI) |

||

| Line and Base Maintenance Form | Component Shop Form | Engine Shop Form |

| Demographics | Demographics | Demographics |

| Planning (A) | Incoming inspection check | Incoming check |

| Prepare for removal (B1) | Prepare for removal | |

| Removal (B2) | Disassembly | Removal |

| Prepare to install (B3) | Prepare to install | |

| Install (B4) | Assembly | Install |

| Installation test (B5) | Installation test | Installation test |

| Close-up/complete restore (B6) | Complete restore | Close-up/complete restore |

| Troubleshooting/deferral (C) | Fault isolation and repair | |

| Cleaning and non-destructive testing inspection | ||

| Additional threat(s) | Additional threat(s) | Additional threat(s) |

Twenty-three observers from CDG and ORY were trained in-house in French, a decision based on prevailing proficiency in this language. The observer training was expanded to one-and-a half days; theoretical content, classroom practice and field practice each took half a day. The AFI MLOSA project team created and integrated new examples applicable to the Component Shops environment.

The Phase 2 target population comprised 700 AMTs at CDG and ORY. For the two airports, 300 observations were scheduled on tasks such as avionics components overhaul, mechanical/pneumatic/air conditioning/flight controls components repair/overhaul, parts machining, NDT inspections, wheel/tire repair or overhaul, escape slide overhaul, and oxygen system components overhaul.

As of this September, 301 observations had been completed in the Component Shops. AFI has received positive feedback from the AMTs involved in the program, and the data produced by LOSA observers were considered detailed and of high quality. The next step in Phase 2 will be data analysis for the Component Shops.

The MLOSA project team has scheduled Engine Shops — a business unit with 600 AMTs — to be the focus of Phase 3 during the third quarter of 2016. The schedule calls for 40 observers from CDG and ORY to be trained and then to conduct more than 300 observations of specified tasks such as CF6/CFM56/GE90/GP7200 engine overhaul, engine line replaceable units repair/overhaul, engine component NDT inspections, and engine test cell inspections.

Data Analysis So Far

AFI working groups dedicated to MLOSA have performed five major steps of safety-diagnostic analysis — combining manual calculations and Minitab statistical analysis software — for the observation data collected with the Excel data-entry forms. These steps were factors analysis to determine TEM profiles; detailed prevalence (frequency) analysis; statistical testing performed to validate correlations and calculate probability of threats and errors using multinomial logistic regressions; statistical interaction analysis and transposition to the AFI risk model (bow-tie model) to build safety key performance indicators (KPIs) and determine barriers; and setting targets for improvement (recommendations to AFI).

Deployed as subject matter experts, the AMT observers later described themselves as “empowered” by their new MLOSA duties. The observers helped the MLOSA project team come up with both accurate diagnoses of issues and successful solutions to them. They also provided recommendations to improve AFI safety management overall.

Through MLOSA, AFI identified some systemic issues across the board — independent of aircraft type or maintenance task — and corresponding precursor latent conditions. The MLOSA observations from Phases 1 and 2 revealed four predominant types of threats, categorized as individual factors, organizational factors, information/technical documentation and tools/supplies. The MLOSA project team’s diagnosis resulted in a plan of corrective actions, which was tracked by AFI safety assessment groups chaired by executive management to assess effectiveness and outcomes.

AFI specifically was able to capture best practices such as cohesive teamwork, compliance with the anti–foreign object debris/damage (FOD) plan and self-initiated promotion of safety culture by many of the observers or by the other AMTs.

Success Stories

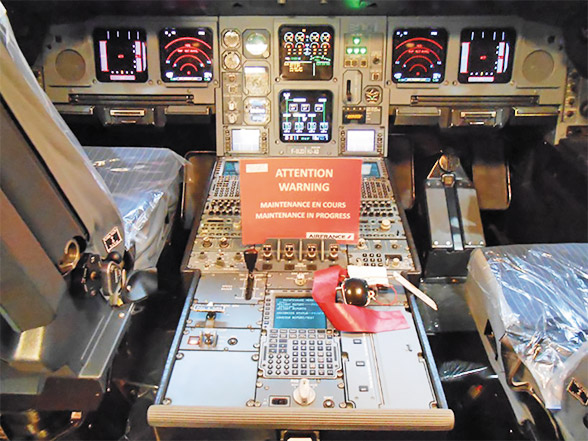

The MLOSA program helped AFI identify several systemic issues and, consequently, systemic solutions that can be applied across the fleet. For example, based on Phase 1 findings, AFI improved its “Change of Oxygen Bottle/Cylinder” task procedures for multiple aircraft types (e.g., Airbus 320/330/340 and Boeing 777/747). This solution used an integrated approach by introducing a new communication procedure and tool (Figure 1) to facilitate coordination and reduce errors due to routine interactions between maintenance personnel and flight crews.

Figure 1 — New Communication Procedure and Tool for AMTs

AMTs = aircraft maintenance technicians

Source: Air France Industries (AFI)

The revised elements of this task introduced anti-FOD toolboxes dedicated to oxygen bottle/cylinder replacement. The toolboxes have specific fitted spaces to help AMTs ensure replacement of each tool used, and they contain materials required for leak tests. Other improved elements are simplified provisioning processes for oxygen cylinders and consumables (e.g., the O-ring for the flared tube), and a working group dedicated to modernize maintenance human factors training. The new training promotes the desired safety culture and emphasizes safety strategies to prepare AMTs for challenging situations in the field. Upon completion of this new recurrent training, AMTs sign a pledge (see “Aircraft Maintenance Technician Safety Pledge”) that complements the existing corporate-level safety pledge.

Air France Industries

Aircraft Maintenance Technician Safety Pledge

- I incorporate safety as a daily essential in each of my activities.

- I have a professional attitude for the benefit of safety and regulatory compliance.

- I ensure continued awareness and I act accordingly.

- I respect the maintenance standards in the work I carry out.

- If in doubt, I choose safety, and I alert my management.

- I am aware of my limitations and I question myself.

- I adopt a transparent attitude; I report my difficulties/malfunctions.

— MM and CZ

Lessons Learned

AFI attributes the MLOSA program’s positive outcomes to careful preparation through cohesive teamwork; the high level of commitment by executive management; the enthusiasm shown by the observers; and the training and support received from Boeing. Executive management credits program-level leadership and its self-assessment of implementation-launch readiness, especially the preparations for the marketing campaign, the customized posters and the special tool kits for recruiting the observers.

Part of this preparation for MLOSA launch was a discussion of “what if” scenarios in case the implementation did not go as planned. For example, the project team members asked themselves, “If AMTs do not accept MLOSA, what should we do?” This risk assessment in turn led to pre-planned mitigation solutions.

The MLOSA project team used AFI Flight Safety Forums as a key venue to promote LOSA and customized its communication media and messages to audiences from different business units. They also had to ensure they were ready to respond to many questions — such as, “How is MLOSA related to other safety programs?” In the communication campaign rollout, they emphasized a motivational message: “Talent wins games, but teamwork and intelligence win championships.”

Executive management showed strong commitment to the program and the required changes in several ways. One example was the co-signing of a memorandum of understanding with AMT labor groups — clearly specifying how MLOSA data and results would be used — by leaders of AFI Engineering and Maintenance Management and the AFI Quality Assurance Directorate. MLOSA also was incorporated into AFI’s SMS annual action plan. Hervé Page, senior vice president of maintenance and engineering, AFI, visited each session of MLOSA observer training to thank the AMTs for their contribution.

Anne Brachet, executive vice president, AFI, told employees at the end of Phase 1, “Involvement of aircraft maintenance technicians in maintenance safety initiatives is a key factor for removing the barriers to flight safety. Our first MLOSA campaign has been a tremendous opportunity to collect safety-minded data to appraise our performance and continue safety promotion within our organization. Commitment deployed by all AFI subject matter experts to develop this innovative initiative supports our common goal to expand our safety culture and, therefore, demonstrate AFI KLM Engineering and Maintenance involvement in industry safety standards.”

Executive management also cited frontline managers as crucial in ensuring that procedures are actually followed, and for bringing about true cultural changes in which production leaders govern and improve safety performance while managing operations. Through the MLOSA campaign, people in all relevant AFI business units came to realize, and uniformly agreed, that flight safety depends on collective safety intelligence derived from multiple sources of data, and that each professional has an important role to play in ensuring flight safety.

Currently, the MLOSA manager is supported by one project coordinator and two data analysts. The project team comprised a human resources–labor union specialist (called a social affairs manager), a human factors–regulatory compliance specialist, a worker-production specialist, a communication specialist, a LEAN transformation/efficiency expert, and a corporate change–management specialist.

Finally, AMT observers and safety coordinators from CDG and ORY asked many insightful questions during observer training. Their practice observations in the Boeing 777 hangars were productive for everyone. During actual observations, the MLOSA project team and safety coordinators kept in close contact with the observers on a weekly basis.

AMTs came to understand the underlying safety theory and processes much better over time through their personal participation directly or indirectly. As a result, their perceptions of, and attitudes toward, the MLOSA program became more positive. As trust in MLOSA grew, the AMTs became more interested in program details and in taking part.

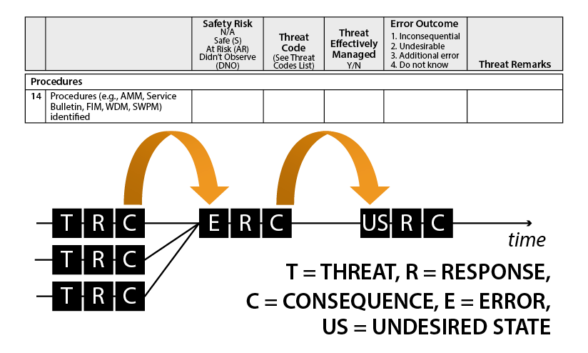

Because its working groups included flight safety coordinators and safety experts conducting data verification and analysis, the MLOSA project team was able to summarize results quickly and to disseminate best practices and tips to the observers. For example, 80 percent of an observer’s time/description tasks, they said, should be spent on recording/describing threats, errors and consequences; 20 percent of time/description tasks should be spent on recording/describing contextual information. Moreover, their Phase 1 observations led to creating a new task-flow logic (Figure 2) taught during Phase 2 observer training, which improves how observers focus their attention and capture the most useful data.

Figure 1 — “What to Look For” Logic for MLOSA Observers

MLOSA = Maintenance Line Operations Safety Audit/Assessment

Source: Air France Industries (AFI)

Concluding Insights

In summary, AFI’s MLOSA program introduced a “bottom-up” process for collecting maintenance safety data — a process made possible by the frontline AMT volunteers, who were selected because of each individual’s desire to promote and constantly improve safety culture. This process carried forward from the Flight Safety business unit’s need to obtain an accurate understanding of day-to-day operations, and from their mantra: “Without data, you are just another person with an opinion.” The MLOSA program similarly transformed a basic concept into a new capability — conducting organizational self-assessment diagnoses of systemic safety issues. AFI essentially recognized through MLOSA that such field data are critical for supporting and improving the entire SMS.

On average, an MLOSA program requires an investment of 125 man-hours per AMT observer. The MLOSA project team — citing team members’ experience calculating return-on-investment in other domains — reported a quantifiably positive impact on safety culture and safety climate change. The project team’s drive to further refine the AFI program includes recommending enhancements to the FAA’s model database for M/R LOSA programs.2 The team believes that FAA guideline revisions should include information on how to set up reporting, and should explain how to use the FAA database in its appendix.

Independent recognition of this program’s value3 — especially as a case study for others —has encouraged the leaders of AFI KLM Engineering and Maintenance to pursue collaboration with other airlines and MROs, to share and compare de-identified MLOSA data, and to globally maximize the lessons learned from all MLOSA programs.

Maggie Ma, Ph.D., is a systems engineering engineer at Boeing Commercial Aviation Services. She supports Boeing customers and other maintenance organizations on a wide array of maintenance human factors safety programs. Christine Zylawski is the deputy flight safety manager who leads the MLOSA program for Air France Industries.

The authors will be presenting on MLOSA at the Foundation’s IASS 2016 in Dubai in November. For more information and to register, go to <flightsafety.org/meeting/iass-2016>.

Notes

- Rankin, William; Carlyon, Bill. Boeing Commercial Airplanes. “Assessing the Safety of Ramp and Maintenance Operations.” Aero. Quarter 2 2012, pp. 10–15.

- Ma, Maggie J.; Rankin, William L. FAA Office of Aerospace Medicine. Implementation Guideline for Maintenance Line Operations Safety Assessment (M-LOSA) and Ramp LOSA (R-LOSA) Programs, Final Report. DOT/FAA/AM-12/9, August 2012.

- For the second consecutive year, Aviation Week selected AFI KLM Engineering and Maintenance for the 2016 MRO of the Year Award in the “Outstanding Airline Maintenance Group” category <www.airfranceklm.com/en/news/afi-klm-em-once-again-voted-mro-year-aviation-week>.

Featured image: © Air France Industries