Within 15 minutes of receiving indications of a fire on the main cargo deck the night of July 28, 2011, the flight crew of an Asiana Airlines Boeing 747-400 freighter found that they could neither reach a nearby airport nor conduct a controlled ditching in the Yellow Sea below.

The fire had begun in or near pallets containing dangerous goods — including highly flammable liquids and lithium batteries — and had touched off explosions that breached the fuselage and sprayed the right wing with debris. Smoke filled the cockpit, and heat destroyed vital flight control components in the aft section of the freighter.

The pilots eventually found themselves unable to control the trajectory of the aircraft, which struck the water 130 km (70 nm) west of Jeju Island, South Korea.

Only small portions of the wreckage and cargo were retrieved from the sand and mud at the bottom of the sea during a search spanning two years. Among the items that eluded searchers were the flight data and cockpit voice recorders.

“No physical evidence of the cause of the fire was found,” said the Republic of Korea’s Aircraft and Railway Accident Investigation Board (ARAIB) in the English translation of its final accident report, published in July 2015.

In the report, the ARAIB concluded that “a fire [erupted] on or near the pallets containing dangerous goods [and] rapidly escalated into a large uncontained fire [that] caused some portions of the fuselage to separate from the aircraft in midair, thereby resulting in the crash.”

Dangerous Goods

The 747 was being operated by Asiana Airlines as scheduled cargo flight AAR991 from Incheon, South Korea, to Singapore. Acquired new by the airline in 2006, the aircraft had accumulated 28,752 flight hours and 4,799 cycles.

The 747 was being operated by Asiana Airlines as scheduled cargo flight AAR991 from Incheon, South Korea, to Singapore. Acquired new by the airline in 2006, the aircraft had accumulated 28,752 flight hours and 4,799 cycles.

Among the cargo pallets, or unit load devices (ULDs), loaded aboard the freighter for the flight to Singapore were three containing dangerous goods. These pallets were loaded on the main cargo deck adjacent to the main cargo door.

The dangerous goods included: 244 kg (538 lb) of 6-cell and 12-cell lithium-ion batteries intended for use in hybrid motor vehicles; 957 L (253 gal) of Photo-Resist, flammable liquids used in the production of integrated circuits and liquid crystal displays; one 5-L (1-gal) container of a corrosive polyamines solution used as an anti-static agent; 12 L (3 gal) of paint used to moisture-proof mobile phones; and 0.2 L (0.2 qt) of lacquer, a flammable liquid used for seal inspection.

Investigators determined that the dangerous goods had been stored, handled and loaded in accordance with existing regulations. (However, the investigation resulted in recommendations for improvement.)

AAR991 Flight Crew

Both pilots assigned to AAR991 had served in the South Korean air force before being hired by the airline. The captain, 52, joined Asiana Airlines in 1991. He served as a 737 and 747-400 first officer before upgrading as a 737 captain in 1996 and as a 747-400 captain in 2001. He had 14,123 flight hours, including 6,896 flight hours in 747s, with 5,666 flight hours as pilot-in-command in type.

“His colleagues stated that the captain was active and very considerate of others’ feelings,” the report said. “His medical record shows that he had no special medical history or hospitalization record, and that he had no health problem which could have affected his flight performance.”

The first officer, 43, joined the airline in 2007. He flew as a 767 first officer until upgrading to first officer on the 747 in November 2010. He had 5,211 flight hours, including 492 flight hours in type.

“His family and colleagues stated that the first officer was a family man … with a strong sense of responsibility,” the report said. “His medical record shows that he had never had special medical history or a hospitalization record since hired.”

Emergency Descent

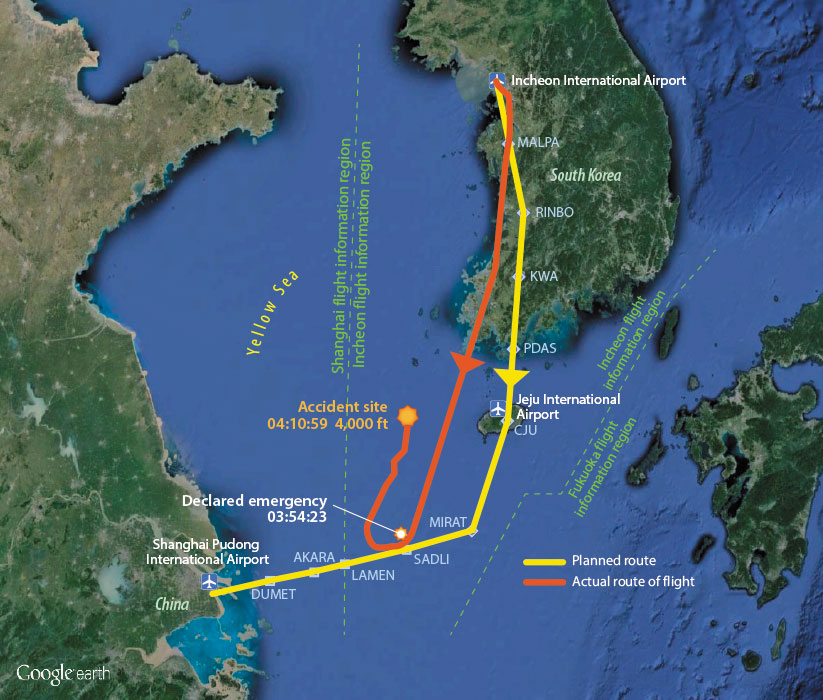

The aircraft departed from Incheon at 0304 local time and was routed by air traffic control (ATC) southwest along the west coast of Korea. Weather conditions generally were clear, with no turbulence.

The flight progressed without incident until 0354, when the crew received an engine indicating and crew alerting system (EICAS) message indicating that a fire had been detected on the main cargo deck. The aircraft was over the Yellow Sea at this time.

“As the captain in a B747 freighter’s cockpit could not accurately check the size and the condition of a cargo fire … it may have been difficult for him to determine whether the fire could be suppressed and how serious it was,” the report said.

At the time, the aircraft was cruising at 34,000 ft on a heading of 202 degrees. The first officer reported the fire to Shanghai Area Control Center (ACC), declared an emergency and requested clearance for an immediate descent to 10,000 ft. The controller approved the request.

Shortly thereafter, the first officer advised that they were diverting the flight to Jeju International Airport, a designated en route alternate airport located on an island south of Korea. The aircraft was about 231 km (125 nm) southwest of the airport at the time. The Shanghai controller told the crew that they could turn at their discretion.

A recording of ATC radio communications indicated that the crew had donned their oxygen masks, and messages automatically transmitted by the aircraft communications addressing and reporting system (ACARS) indicated that the captain had disengaged the autopilot and was flying the aircraft manually.

Checklist Confusion

The report said that the pilots likely conducted various quick reference handbook (QRH) procedures in response to numerous EICAS messages related to the rapidly spreading fire.

Among the QRH procedures the crew likely conducted were those on the “Fire Main Deck” checklist. It is important to note that the QRH available to the pilots contained separate checklists for the passenger, combined passenger/cargo (combi) and freighter versions of the 747-400, all of which were in service with Asiana.

Differentiation among checklists with the same title was achieved by showing the registration numbers of the aircraft in Asiana’s fleet for which the checklist was applicable.

Thus, the QRH available to the pilots contained “Fire Main Deck” checklists for both the 747-400 combi and freighter (the passenger version does not have a main cargo deck). The report said there were indications that the AAR991 crew inadvertently selected the “Fire Main Deck” checklist for the combi aircraft, not noticing that it did not show their aircraft’s registration number (HL7604). The combi checklist precedes the freighter checklist in the QRH’s sequence of pages.

The report said that among the differences between the checklists was that the one for the combi — which, unlike the freighter, does not have a cargo compartment classified as a Class E compartment — did not include the requirement on the freighter checklist to “expedite a climb or descent to 25,000 ft when conditions and terrain allow.”1

The report said that Boeing chose 25,000 ft for the freighter because the ambient pressure and oxygen concentration at that altitude are optimal for suppressing a fire in a Class E cargo compartment. Going to a lower altitude increases ambient pressure and oxygen concentration to levels less conducive to fire suppression.

Another difference between the checklists is that the step requiring depressurization of the cabin, a key element in suppressing a main cargo deck fire, appears later in the combi checklist than on the freighter checklist.

Investigators determined that, by using the combi checklist rather than the freighter checklist, the crew’s action to depressurize the cabin might have been delayed by about two minutes.

“AAR991’s late action to suppress fire (depressurization) and loss of opportunity to suppress fire at 25,000 ft likely contributed to the spread of fire, based on the theory that the minimum re-ignition energy varies inversely with the square of pressure,” the report said.

Although these points reveal important lessons in the design and use of checklists, they may have been moot to the situation facing the AAR991 crew. Investigators determined that if the pilots had conducted the appropriate “Fire Main Deck” checklist, the fire might not have been fully suppressed by the time they needed to begin their descent to Jeju.

“Judging from the size and condition of AAR991’s fire, there is a possibility that … an increase in oxygen during the descent [might have] resulted in the spread of fire, [and] the outcome of this accident would not have changed,” the report said.

Communication Problems

The Shanghai ACC controller lost radio contact with AAR991 at 0358, as the aircraft was descending rapidly through 19,000 ft and continuing its turn toward Jeju Island. The 747 had descended below Shanghai’s radio-coverage area.

The controller asked the flight crew of a nearby Korean Airlines (KAL) aircraft to relay information to the Asiana pilots. The KAL crew established radio communication with the 747 crew and subsequently relayed to the Shanghai controller their request for a radar vector to the Jeju airport. A heading of 045 degrees was handed off in this manner at 0359.

The report said that numerous ACARS messages concerning mechanical issues related to the fire were transmitted during this time. However, the messages ceased at 0400, likely because the ACARS management unit had been damaged by the fire or the crew, attempting to re-establish radio contact with the Shanghai ACC, had selected the very-high-frequency channel used for ACARS transmissions.

About the time the ACARS messages ceased, the KAL crew relayed an instruction from the Shanghai controller to change to a radio frequency for the Incheon ACC. However, the 747 first officer advised that they were unable to establish communication on that frequency. A different radio frequency, for the Fukuoka ACC, then was relayed to AAR991.

The first officer’s attempts to establish radio communication with Fukuoka were unsuccessful. The Shanghai controller then asked the KAL crew to relay information between AAR991 and both the Shanghai and Incheon ACCs. (There was no direct telephone line between the centers.)

Contact Lost, Control Lost

Radar data recorded at 0401 showed that the 747 was at 8,200 ft and on a heading of 033 degrees. The aircraft then began to climb to 10,300 ft and continued to deviate left of the previously assigned heading of 045 degrees.

“After this, AAR991’s altitude, ground speed and heading changed inconsistently,” the report said, noting that the deviations likely were due to smoke in the cockpit and degraded flight control.

The aircraft was about 204 km (110 nm) southwest of Jeju at 0405 when instructions by the Incheon ACC to maintain a heading of 060 degrees and to descend to 7,000 ft were relayed to the Asiana crew. The captain of the 747 partially acknowledged the instructions, saying, “descend 7,000 feet.”

At 0406, the captain radioed that “rudder control is not working” and advised that the rudder seemed to be jammed. Shortly thereafter, he said, “We have to open the hatch.” According to the report, this transmission referred to the cockpit smoke shutter (vent).

‘Going to Ditch’

Although the 747 was getting close to the Jeju airport, the smoke building in the cockpit, and the continuing systems failures and flight control difficulties related to the rapidly spreading fire apparently led the crew to consider the possibility that they would have to ditch the aircraft.

The report said that the crew might have been able to successfully ditch the aircraft if they had started as soon as the fire was detected. At this point, however, they did not have sufficient control of the 747 to effect a ditching.

Portions of aft fuselage frames that later were retrieved showed severe thermal damage. “Although flight control components that ran along the crown area in the aft section of the aircraft were not retrieved, they [too] likely sustained severe thermal damage,” the report said.

The report noted that the 747 QRH states: “It must be stressed that for smoke that continues or a fire that cannot be positively confirmed to be completely extinguished, the earliest possible descent, landing and evacuation must be done. … In a severe situation, the flight crew should consider an overweight landing, a tailwind landing, an off-airport landing, or a ditching.”

At 0409, the KAL crew relayed an instruction from the Incheon ACC for the Asiana crew to change to a radio frequency that would put them in contact with the Jeju ACC. Shortly thereafter, the Asiana captain transmitted the following message on the new frequency: “Rudder control … flight control … all are not working.”

The first officer then asked Jeju ACC if they had heard the transmission, and the controller responded, “Yes, I can hear you.”

“We have heavy vibration on the airplane, may need to make an emergency landing, emergency ditching,” the first officer said.

The Jeju controller replied, “Yes, say again, please.”

“Altitude control is not available due to heavy vibration,” the first officer said. “Going to ditch.” (The report said that the “heavy vibration” likely resulted from fuselage skin that sheared off due to the dangerous-goods explosions.)

At 0410, the controller asked the crew if they could conduct an approach to Jeju International, but there was no response. Subsequent attempts to hail the AAR991 pilots were unsuccessful. The aircraft was descending through 4,000 ft when ATC radar contact was lost.

Mud, Sand, Murk

The aircraft was in a rapid descent when it struck the sea at 0411. “Due to the crash impact and fire, the captain and the first officer were fatally injured, the aircraft was destroyed, and the cargo shipments were damaged, incapable of being recovered or washed away,” the report said.

Only a portion of the wreckage, including about 40 percent of the fuselage skin and 15 percent of the cargo, was recovered from the sea floor, about 87 m (285 ft) below the surface of the Yellow Sea.

“The sea floor, generally flat, consisted of mud and sand about 60 cm [24 in] thick, but the currents flowed fast, at 2-4 m/sec [7-13 ft/sec], and the average visibility at the sea floor was just 0.5 meters [1.6 ft],” the report said.

Areas of the main cargo deck near the dangerous-goods pallets had “shattered into many pieces due to dangerous goods’ explosive energy,” the report said. Residues of the flammable liquids and paint were found on the upper surface of the right wing, and small electronic devices packaged among the cargo were found embedded in composite wing structures.

The energy that caused this “was generated by fire-induced explosion of flammable materials and lithium-ion batteries,” the report said. “The ARAIB assumes that a fire likely broke out first on or near the pallets containing the dangerous goods, but physical evidence of the cause of the fire was not found.”

Changes Sought

The investigation revealed that Asiana Airlines’ 747 flight simulator was configured as a passenger aircraft, precluding adequate training for fighting a main cargo deck fire in a freighter. This finding led the ARAIB to recommend that the airline modify the simulator so that pilots can be “realistically trained” on abnormal procedures for all versions of the 747 in its fleet.

Although an ACARS message indicated that the emergency locator transmitter (ELT) was activated, likely by the pilots, 10 minutes before the aircraft crashed, no ELT signal was received by ground or search and rescue personnel. The report noted that “the ELT installed on AAR991 is inoperable in the water.”

The ARAIB concluded that “current ELTs installed on aircraft flying over maritime areas need to be improved to float to the surface and operate, be operable in the water or broadcast the GPS [global positioning system] location so that the location of missing pilots and airplanes can be rapidly and accurately identified.”

The board also recommended that the regulations governing the transport of dangerous goods be revised to require that flammable goods and lithium batteries be carried “only in Class C cargo compartments equipped with a separate smoke detector or fire detection system and with an approved built-in fire extinguishing or suppression system controllable from the cockpit.”2

In addition, lithium batteries should be loaded only in ULDs containing no other dangerous goods, the ARAIB said. The board noted that although the investigation attempted to, but did not, “acquire the data that could prove the self-ignition possibility of lithium-ion batteries in normal conditions of transport,” it has been shown that “when they are heated externally, they can go into thermal runaway.”

This article is based on the English translation of Republic of Korea Aircraft and Railway Accident Investigation Board Aircraft Accident Report ARAIB/AAR1105, “Crash Into the Sea After an In-Flight Fire, Asiana Airlines, Boeing 747-400F, HL7604, International Waters 130 km West of Jeju International Airport, 28 July 2011.”

Notes

- U.S. Federal Aviation Regulations (FARs) Part 25.857 defines a Class E cargo compartment, in part, as one having a “separate approved smoke or fire detector system,” a “means to shut off ventilating airflow to, or within, the compartment” and “means to exclude hazardous quantities of smoke, flames or noxious gases from the flight crew compartment.”

- FARs Part 25.847 defines a Class C cargo compartment, in part, as one having a “separate approved smoke detector or fire detector system,” an “approved built-in fire extinguishing or suppression system controllable from the cockpit,” “means to exclude hazardous quantities of smoke, flames or extinguishing agent from any compartment occupied by the crew or passengers,” and “means to control ventilation and drafts within the compartment so that the extinguishing agent used can control any fire that may start within the compartment.”

Further Reading

Pierobon, Mario; Jackman, Frank. “Dangerous Goods.” AeroSafety World Volume 10 (September 2015): 39–44.

Werfelman, Linda. “Packing Up.” AeroSafety World Volume 10 (February 2015): 37–40.

Jackman, Frank. “Top 10 Safety Issues: Lithium Battery Carriage.” AeroSafety World Volume 9 (December 2014–January 2015): 15.

Featured image: © Daniel Alaerts|AirTeamImages

Cargo: © Korea Aircraft and Railway Accident Investigation Board

Flight path: © Korea Aircraft and Railway Accident Investigation Board; background: © Google Earth

Wreckage remnants: © Korea Aircraft and Railway Accident Investigation Board