With more than half of U.S. aviation maintenance personnel now 45 years of age or older, increasing numbers are facing the prospect of diminished hearing and vision, and other age-related ailments.

In some cases, the hazards associated with these ailments can be managed and their harmful effects — both on the maintenance technician and the operator — can be limited, aeromedical specialists say.

Data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) show that of 153,000 aircraft mechanics and service technicians in the United States in 2012, some 75,000 were between the ages of 45 and 64; an additional 5,000 were 65 years of age or older. Their median age was 44.8 years.1

Overall, the U.S. work force is getting older, the BLS said, adding that, while those aged 55 and older made up 11.8 percent of the total work force in 1992, the percentage increased to 20.9 percent by 2012 and is forecast to climb to 25.6 percent by 2022.2

“The aging workforce phenomenon is real,” the U.S. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) said. “These demographic shifts have made the issue of healthier workers, especially those of advanced age, much more pressing.”3

As the work force ages, health officials and aeromedical specialists have begun calling attention to the most common age-related conditions.

For aging aviation maintenance personnel, like many other older workers, a primary issue is presbyopia — difficulty focusing the eyes on close objects — that affects most people by the time they are in their 40s but may become apparent several years earlier, typically when it becomes difficult to read fine print.4

For aging aviation maintenance personnel, like many other older workers, a primary issue is presbyopia — difficulty focusing the eyes on close objects — that affects most people by the time they are in their 40s but may become apparent several years earlier, typically when it becomes difficult to read fine print.4

For most people, the ability to focus on objects at an intermediate distance also deteriorates, typically by the time they reach 50.

The focusing difficulty is a result of a decline in the flexibility of the eye’s lens, caused by years of accumulation of dead lens cells, which are compacted in the outer portions of the lens.

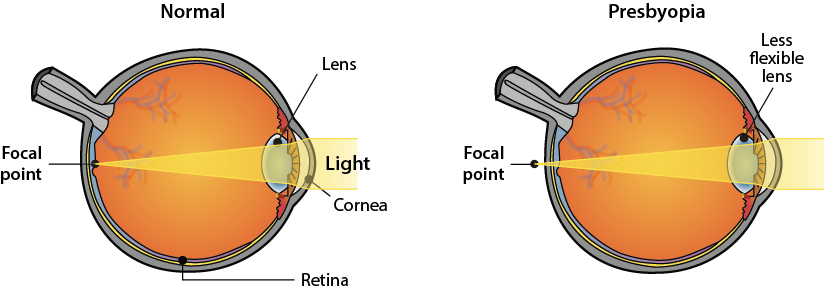

The lens is the structure in the eye that focuses light on the retina, the eye’s innermost lining (Figure 1). The retina translates the image into electrical impulses, which travel along the optic nerve to the brain. When a person is young, the lens is flexible and easily changes shape, depending on the distance of the object being viewed — the lens becomes rounder to view a near object and thinner to view an object in the distance. But with age and the accumulation of dead lens cells, the lens is less capable of becoming rounder and, therefore, the eye is less able to focus on nearby objects.

Figure 1 — Normal and Presbyopic Eyes

Note: Light enters the cornea and passes through the lens. In a young person, the lens is flexible and its curve adjusts to bring objects into focus, with the focal point on the retina. In presbyopia, the lens is less flexible; this moves the focal point behind the retina, making near objects appear blurry.

Credits: eye: Rhcastilhos | Wikimedia; presbyopia diagram: Bruce Blaus | Wikimedia

James W. Allen, a retired U.S. Navy physician and consultant to human relations and safety departments, describes presbyopia as a “major signpost in the aging process.”5

Allen, who has written a series of articles discussing presbyopia and other age-related latent medical and environmental conditions (LMECs) for the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration’s (FAA’s) Aviation MX Human Factors quarterly newsletter, said that the loss of near vision has considerable impact on a maintenance technician’s job performance.

“Consider visual inspection of the aircraft, a major duty for most AMTs [aviation maintenance technicians],” Allen wrote, noting that FAA Advisory Circular (AC) 43-204, Visual Inspection for Aircraft, which describes the inspection process, assumes that the inspector has good visual acuity.

“The AC’s assumption of good visual acuity may be incorrect considering the aging of the workforce,” Allen added. Prescription eyeglasses or over-the-counter reading glasses can help, but only if the maintenance technician understands how the glasses’ lens design will place objects in focus, he said, adding that “head and eye movement may be necessary to ensure clear vision of the work under inspection.”

Although in the past, presbyopia and other LMECs facing older maintenance personnel have been outside the scope of safety management systems (SMS), Allen said that in the future, SMS should be developed with LMECs in mind.

“The first step is a risk assessment of those work processes that require inspections,” he said. “Common considerations involve the tradeoff between speed and accuracy of the inspection process. From this assessment, the manager can determine the potential risk from presbyopia. Education of the employees, especially mechanics over the age of 52 years, provides awareness training to those most likely affected by presbyopia.”

Hearing Loss

Presbycusis or age-related hearing loss, is another “signpost of aging,” Allen said, although he noted that hearing loss is not inevitable and that it often is caused not by aging but by exposure to noise, solvent or fuels. In fact, these exposures, not presbycusis, are the major cause of hearing loss in older workers, he said.6

Regardless of the cause, he wrote, “Without adequate hearing, the workplace becomes dangerous. The hearing-impaired individual may not understand instructions, respond to a warning or localize a sound. … Similar to other … LMECs, hearing loss does not cause accidents; rather, they form a link in the accident chain.”

Regardless of the cause, he wrote, “Without adequate hearing, the workplace becomes dangerous. The hearing-impaired individual may not understand instructions, respond to a warning or localize a sound. … Similar to other … LMECs, hearing loss does not cause accidents; rather, they form a link in the accident chain.”

He cited earlier research in estimating that workers over age 55 are four times more likely to have hearing loss than those younger than 25, that those who have worked in aviation for many years are especially at risk and that 20 percent of aviation maintenance technicians have experienced a significant hearing loss. He recommended that SMS, as well as workplace health and safety programs, promote hearing protection.

“Development of a human factors–oriented [health and safety] program requires a prioritized set of activities that will limit the potential for miscommunication during maintenance activities,” Allen wrote. A human factors–based program would ensure that all maintenance technicians “have a basic level of hearing,” and also limit noise in work areas and take hearing loss into account in handing out work assignments, he added.

‘A Link in a Chain’

Another LMEC is obesity, Allen said, citing 2010 data indicating that more than one-quarter of U.S. workers were obese — that is, that their body mass index (BMI) measurements yielded a score of more than 30. BMI is a way of measuring body fat that takes into account an individual’s height and weight; for example, someone 6 ft (2 m) tall would be considered obese if he or she weighed 221 lb (100 kg) or more.7

Although research has not determined that obesity presents a risk to aviation safety, Allen said that maintenance facilities may nevertheless want to take steps to classify obesity as an LMEC — a “link in a chain leading to maintenance error.”

Although research has not determined that obesity presents a risk to aviation safety, Allen said that maintenance facilities may nevertheless want to take steps to classify obesity as an LMEC — a “link in a chain leading to maintenance error.”

Obesity fits the definition of an LMEC, he said, because of the medical costs and indirect costs associated with the condition, which increases the risk of contracting a number of other conditions, including coronary heart disease, stroke, hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus. He cited data showing that in addition to the $147 billion paid by government and private insurers in 2008 to treat these conditions, indirect costs include an estimated $8.65 billion a year in obesity-related workplace absenteeism.

Studies of obese workers in Canada, China and Sweden found similarly large losses in productivity, he said.

“While absence from work is one measure of productivity, research indicates that obese workers are less productive when on the job,” he said, adding that, in comparison with colleagues of normal weight, they typically have more trouble concentrating or work more slowly.

“Warnings from public health officials, analysis of cost from presenteeism [loss of productive time while at work] and similarities between obese and fatigued workers significantly support the recognition that the obese AMT poses a risk to air safety,” Allen said. “Obesity contributed to … error-prone behavior at work.”

He said that workplace health programs can mitigate the ill effects of obesity, in much the same way that fatigue risk management programs can mitigate the effects of fatigue and that “implementing a risk management program that recognizes obese workers allows [an SMS] to proactively manage a workplace hazard.”

Hazardous Substances

Workplace exposure to hazardous substances also constitutes an LMEC, Allen said.

“Exposures in the workplace can and do cause disease and disability,” he said. “An overlooked consequence of exposure is its effect on the aging worker. Exposures well below published OEL [occupational exposure limits] add to the disease burden in the aging population.”8

As an example, he cited lead in a repair station, which he said “provides an example of both the clinically obvious consequences and the likely formation of an LMEC.”

He relayed the story of a repair station that was visited in 2012 by NIOSH scientists, who found lead dust throughout the station. Lead was present in aircraft fuel, and lead dust was created by sandblasting spark plugs. He said NIOSH blamed “poor shop hygiene, combined with food service inside the work area,” for spreading lead dust throughout the shop.

The workers’ blood lead levels were below the permissible exposure limit, so workers may have assumed incorrectly that their lead exposure had caused them no problems, Allen said.

However, he added, “symptoms of chronic inorganic lead poisoning include such common complaints as headache, joint and muscle aches, weakness, fatigue, irritability, depression, constipation and abdominal discomfort. While OELs may protect the worker from overt symptoms of lead poisoning, they are not sufficient to protect workers from more subtle adverse effects such as hypertension, kidney failure, and reproductive and cognitive effects,” Allen said.

Arthritis and hypertension (high blood pressure) are the two most common health conditions in workers over age 55, and lead exposure contributes to both conditions, he said.

Exposure to other substances has been associated with other medical problems, such as a link between some solvents and cardiac effects; ergonomic stresses and joint and muscle problems; and acrylates and solvents and skin rashes, he said.

Correcting an LMEC caused by workplace exposure to a hazardous substance must take into account the characteristics of the exposure, the type of work process involved and the workplace environment, Allen said.

He cited cases at the start of World War I in which both British and German airplane builders “began to die from a work process involving doping” — shrinking fabric to fit the aircraft fuselage and flight surfaces. In both countries, the process involved tetrachloroethane (TCE), which, after absorption through the skin, caused liver damage and “the long and painful death of many workers.”

In the following years, “engineers developed factories with adequate ventilation, a work process that minimized spills and solvent-resistant aprons with eye protection for the workers,” Allen said. “Deaths from TCE declined dramatically.”

He said similar actions can limit exposure to lead and other hazardous substances that present extra danger to older maintenance technicians, especially those with hypertension, arthritis and other chronic ailments.

Notes

- BLS. Employed Persons By Detailed Occupation and Age, 2012 Annual Averages.

- BLS. Share of Labor Force Projected to Rise for People Age 55 and Over and Fall for Younger Age Groups.

- NIOSH. Productive Aging and Work.

- Mohler, Stanley R. “Early Diagnosis Is Key to Correcting Age-Related Vision Problems Among Pilots.” Human Factors & Aviation Medicine

- Allen, James W. “Presbyopia: Why Near Vision Is Important to the Safety Management System.” Aviation MX Human Factors Volume 2 (September 2014): 5–7.

- Allen, James W. “Aging, Hearing and Managing Risk.” Aviation MX Human Factors Volume 2 (December 2014): 5–7.

- Allen, James W. “An Obese Workforce: Is Aviation Safety Compromised?” Aviation MX Human Factors Volume 3 (March 2015): 5–6.

- Allen, James W. “Exposure in the Workplace: LMEC for the Aging Workers.” Aviation MX Human Factors Volume 3 (June 2015): 6–8.

Featured image: © Derek Pedley | AirTeamImages

Glasses: © malvino | VectorStock

Hearing aid: © mOleks5 | VectorStock;

Mechanic: © Ashva | VectorStock, modified by Susan Reed