It is commonly, if not universally, held that efforts to enhance aviation safety benefit from the sharing of information within departments, across organizations and among industry and government stakeholders encompassing a variety domains, including airlines, air navigation service providers (ANSPs), manufacturers, suppliers and regulators. But sharing data outside of an organization is complicated by a host of factors, including the difficulty of standardizing data and taxonomies across multiple companies and the need to protect proprietary data from potentially inappropriate use.

A diverse group of commercial aviation stakeholders is working on an initiative that will enable the sharing of safety knowledge and experience to enhance overall industry risk management and safety efforts without requiring organizations to share internal data.

The purpose of the Common Aviation Risk Models (CARM) effort is to build a collaborative, international consensus around a set of bow-tie based risk models that “capture (and continuously update) our best understanding of the key risks to aviation globally,” says the CARM 2018 action plan.

According to Tom Lintner, president and CEO of The Aloft Group, a U.S.- and Ireland-based consulting firm, CARM initially was the idea of Bob Dodd, a risk management expert and retired airline safety executive who works with Aloft. “He approached Terry [Eisenbart, Aloft executive vice president] and me and said why don’t we set up something for the good of the industry,” Lintner said.

CARM was founded at an industry conference in Ottawa, Canada, in 2016. It is a voluntary effort for which Aloft does the administrative work and does not receive compensation. CGE Risk Management Solutions, a provider of barrier-based risk management solutions, maintains the CARM bow-tie server, which houses a database of bow-tie diagrams. Some of the bow-tie diagrams were created and shared by CARM member carriers and others were developed by CARM working groups. Other organizations involved in CARM include Air France, Air Transat, Delta Air Lines, American Airlines, Lufthansa Group and Nav Canada.

Lintner traces CARM’s early roots to the U.K. Civil Aviation Authority (CAA), which developed and published bow-ties models for its Significant Seven risks, Lintner said. The Significant Seven risks — loss of control, runway overrun or excursion, controlled flight into terrain, runway incursion and ground collision, ground handling, airborne conflict, and airborne or post-crash fire, were identified in CAA Paper 2011/03, published in March 2011. After identifying the seven issues, the CAA began developing bow-ties to cover each issue.

In August 2015, the CAA published “CAA Strategy for Bowtie Risk Models,” in which it described the bow-tie process as “a methodology to proactively identify and manage weaknesses in the aviation system so that resources can be focused in the most efficient way.”

Air France picked up the concept from the U.K. CAA and developed nearly three dozen bow-tie models of its own, covering flight operations, cargo, maintenance, ground operations, the passenger cabin and human factors. Air Transat, a Canada-based leisure travel airline, leveraged Air France’s bow-tie models and built its own more detailed models and then shared those with Air France, Lintner said. Other CARM members, including American Airlines and Delta Air Lines, also have been developing bow ties.

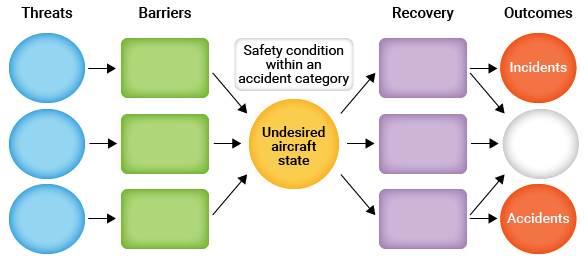

A bow-tie diagram, so named because it looks like a bow tie, is used to help visualize risk. As described by CGE, the basic diagram starts with a hazard. Once the hazard is chosen, the next step is to define the top event, or undesired state, which is the moment “when control is lost over the hazard.” To the far left of the diagram are listed the threats that will cause the top event. On the far right are the consequences that can be expected from the top event. Between the threats and the top event are the barriers in place to prevent the top event from happening, and between the top event and the consequences are barriers put in place to recover from a top event so the event does not escalate into an impact or consequence.

The idea behind CARM is to share knowledge and not data or proprietary practices, Lintner said. When the CARM working groups meet to discuss such topics as unstable approaches and mitigations, “no one cares about how many unstable approaches, they want to know how you mitigate them,” he said. CARM helps shift the focus from incidents to risk.

The plan is to develop a suite of bow-tie diagrams covering all operational phases. The models would provide an improved methodology for risk assessment by states and service providers; a common risk classification structure that supports more detailed and diagnostic monitoring of risk in critical areas; and development of improved safety risk performance measures, according to CARM documentation.

Often, when organizations implement bow-tie based risk management, they start too small, Lintner said, and then the pendulum swings too far to the overly complicated before it settles into a sweet spot. By starting with a set of common models, future users could save themselves as much 18 months of experimentation.

Once the bow-tie models are implemented, organizations can study the barriers to see what is working and identify and address barrier failures, Lintner said.

He sees the CARM development process, which includes working group and larger meetings, as an ideal opportunity for industry stakeholders to have open conversations around safety issues without the historic reluctance to share data.

In a paper published in 2015, Aloft’s Dodd said, “On a global basis, CARM becomes the place where risk understanding can be captured and incorporated continuously. It moves the process away from the existing one-shot accident/investigation/actions process to a global learning ‘engine.’”

Featured image: composite, Susan Reed; background bowtie, © microstocksec | VectorStock

Bowtie diagram: Flight Safety Foundation Global Safety Information Project