Threat forward briefings, in which pilots identify potential threats before departure and again before landing, are a creative process to operationalize the threat and error management model. Mandating the crew identification of threats through standard operating procedures (SOPs) represents an innovative approach to ensuring active engagement in real-time risk mitigation. This paper proposes an advancement of this mandated collaborative risk mitigation process, emphasizing the integration of technology in identifying threats and improving crew communication.

Threat forward briefings began to take shape in the aftermath of a 2013 fatal crash of an Airbus A300-600 freighter. The U.S. National Transportation Safety Board’s (NTSB) final report on the accident said that because the crew did not re-brief when elements of their planned approach changed, they “placed themselves in an unsafe situation because they had different expectations of how the approach would be flown.”1

In 2017, Alaska Airlines Capt. Rich Loudon and Capt. David Moriarty, a member of the Royal Aeronautical Society’s Human Factors Group, wrote in AeroSafety World that the accident was an example of how briefings had become a “one-sided, box-checking” event. They advocated a collaborative briefing and an end to the outdated “your leg, my leg” mindset.

The threat forward briefing initiative seeks to enhance pilot awareness by focusing on the pilot monitoring’s engagement in a collaborative environment to identify potential threats before departure/landing. To facilitate this process, certain airlines have implemented the use of aids such as cards or placards to organize threats into categories like personal, environmental, and others. These aids are designed to jog the memory and provide a framework for threat assessment.

The overall philosophy encourages pilots to move away from traditional briefings that simply recite data such as inbound course, localizer frequency, or missed approach altitude. Instead, crews focus on what is most likely to cause a problem now. For example, “ATIS says there are low-level wind shear advisories. Let’s review the wind-shear escape procedure.”

The implementation of the threat forward briefing has met with widespread approval across the aviation industry, although supporters concede that some pilots might resort to merely citing their card examples mechanically, just to tick off the requirement of conducting a threat-forward briefing, or they might ignore the process altogether.

The primary aim of this paper is to delineate strategies to improve the briefing process. It seeks to refine and expand the existing briefing protocol through data analytics and innovation. This proposed enhancement is designed to sharpen threat identification and institutionalize a framework for crew communication. By systematically integrating data-driven technological tools into the briefing process, this approach seeks to emphasize potential threats, thereby significantly enhancing risk mitigation efforts.

Vulnerabilities

In examining the current model of threat forward briefings, this paper delineates three primary limitations that may undermine the model’s effectiveness: the scarcity of data for pilots, a lack of pilot engagement, and potential self-silencing on safety issues.

Gaps in information dissemination require pilots to integrate data from disparate sources to assess risks. For instance, data on weather, airspace constraints, and mechanical issues come from different sources, and pilot proficiency information is not readily available. Without real-time access to comprehensive data, pilots struggle to preemptively identify and mitigate risks. Addressing this challenge requires integrating advanced data-sharing technologies to provide pilots with real-time, comprehensive insights for better threat assessment.

Redundant procedures, a culture that doesn’t prioritize proactive risk management, or the absence of incentives for thorough briefing participation can lead to a lack of engagement. To address this, a systems-level intervention is crucial, focusing on systemic organizational changes rather than solely relying on individual behavioral change. This approach emphasizes a more holistic and sustainable transformation in practices, which drives attitudes and behavior.

One problem with the current model is that some pilots fail to self-disclose potential threats. These can include, but are not limited to, a lack of recent flying experience, external stressors, and/or concern about past errors. Such reluctance to share personal threats can hinder the identification and mitigation of risks, as these personal factors can impact performance and decision-making capabilities. The operational reality that pilots frequently meet for the first time less than an hour before the threat forward briefing process is a challenge to effective communication and collaboration. Such abbreviated interactions may not allow time for pilots to build the trust and rapport necessary for open dialogue. Academic research has made clear that pilots tend to engage in self-silencing behaviors when the microculture of the flight deck lacks psychological safety.2 This phenomenon is noteworthy given that a captain has only a short time to set a friendly tone and encourage communication prior to conducting the departure briefing. Therefore, formalizing effective crew resource management (CRM) practices, characterized by promoting psychological safety, emerges as a critical strategy for strengthening safety voice.

Leveraging Data

To address the first two challenges (lack of data and lack of engagement), we propose a threat score that compiles data from various sources to give an overall score intended to provide pilots with insight into possible threats. Airlines already collect this data. We are merely advocating for collecting data from disparate sources into a quick reference that offers pilots real-time insight into potential threats.

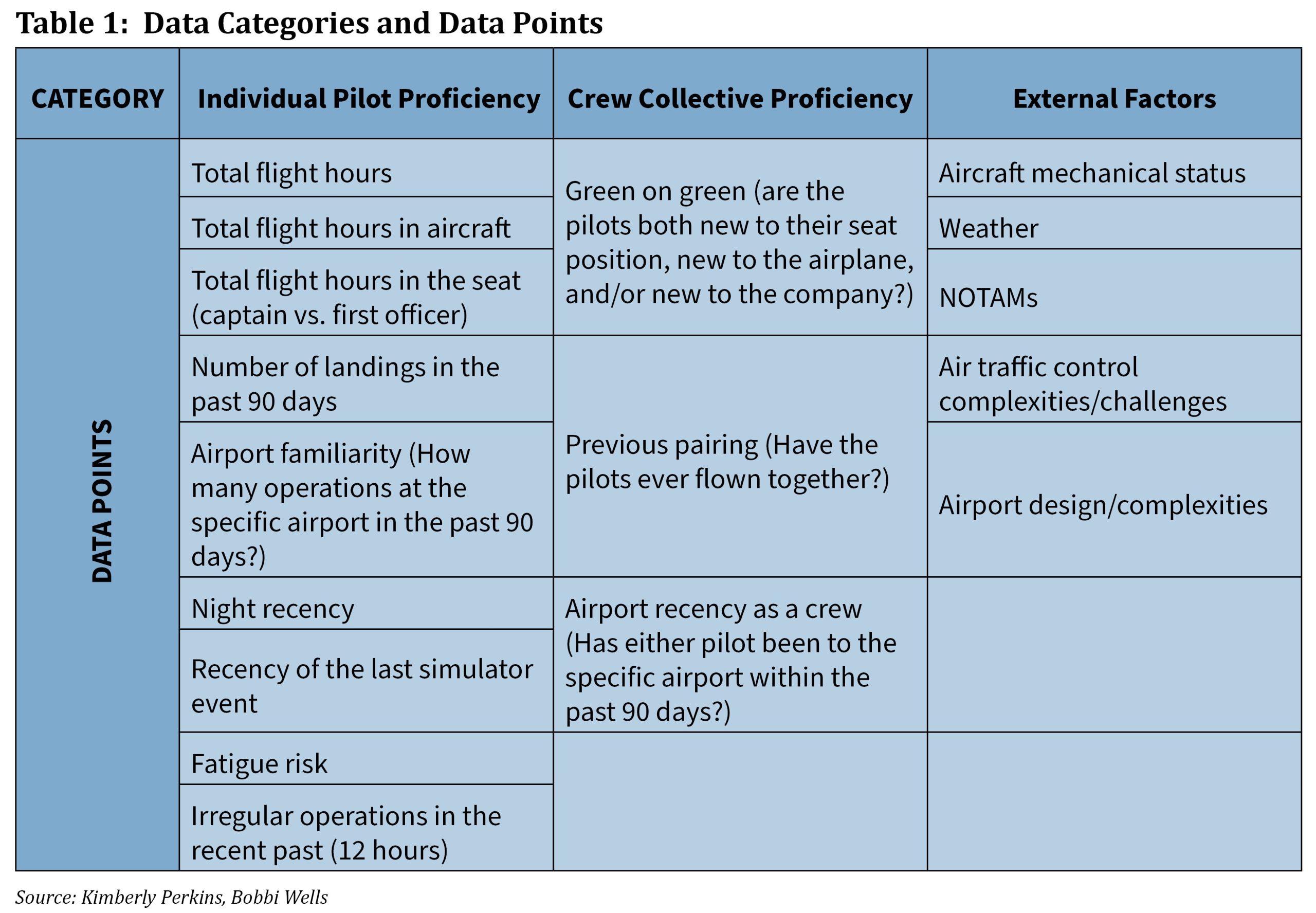

Table 1 offers an example of data being collected by category and the specific data points within each category.

Additional data points can be added as the development of the briefing matures. For example, airlines may not be capturing whether pilots have flown together before. We cannot overstate the value of continually improving the data that makes flight crew briefings more relevant.

The premise suggests that airlines have the data to compute a risk valuation for each variable under consideration. Through mathematical extrapolation, it is possible to derive a risk assessment score utilizing the datasets already available and using risk matrix values.

Employing data obtained from a variety of sources — including properly protected line training evaluations, simulator assessments, flight operational quality assurance trends, line operations safety audits, professional standards reports, and event review committee recommendations — analysts could be equipped to identify potential correlations impacting risk levels. Inquiries into the factors that yield the lowest risk profile could be facilitated by examining extant data. The answer to these questions depends upon analyzing data already accrued by the airline, suggesting that the initial opportunities to elevate risk awareness are embedded within the existing datasets.

A Theoretical Framework

We offer a theoretical framework for how best to operationalize threat identification and systematize threat forward briefings.

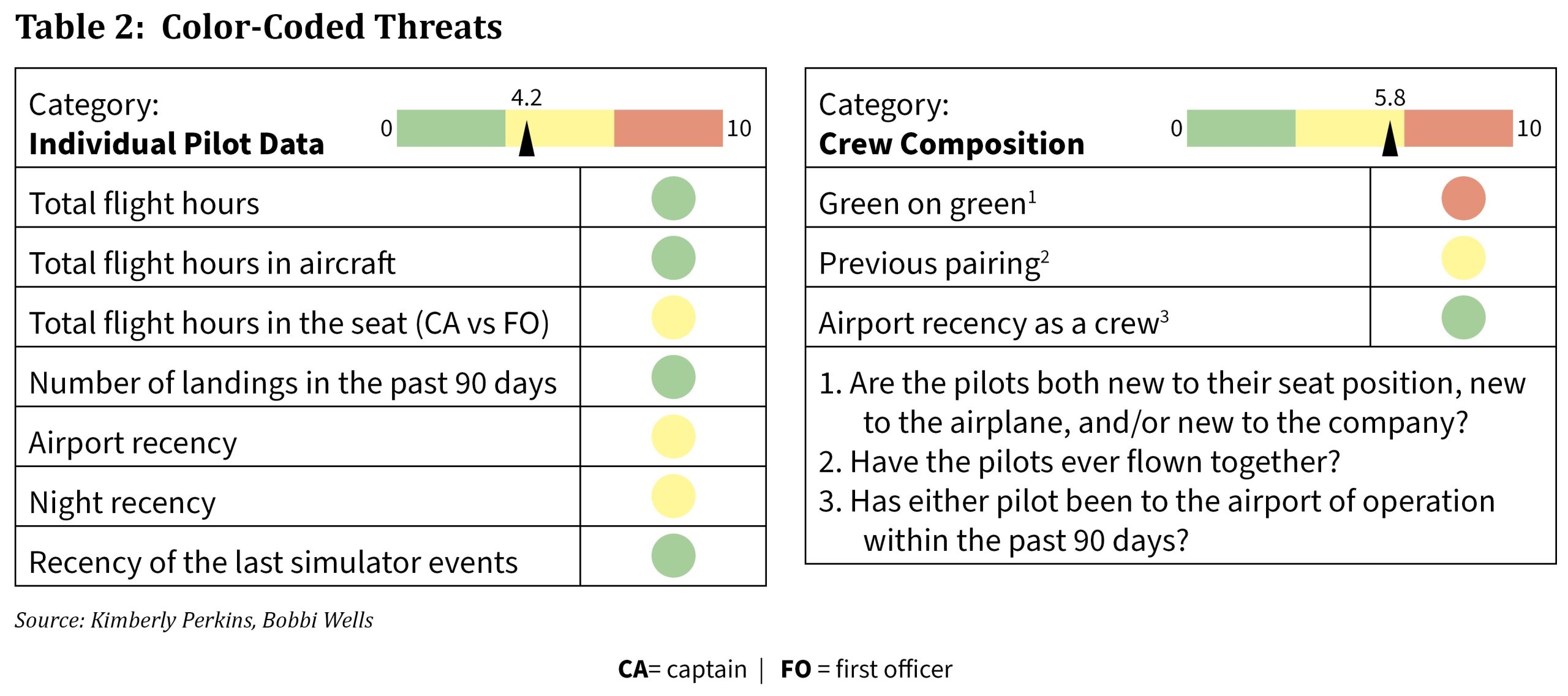

Before crewmembers begin their assigned pairings, their company-issued devices present a sliding color scale — where green denotes the lowest potential for threat, yellow indicates a medium potential, and red signifies the highest potential — providing an automated threat potential score (Table 2). This score is derived from a dataset engineered to assess the potential risk levels associated with each data point and category. Each category is represented by a specific color, contributing to the aggregate potential threat score for each flight. This color-coded system highlights areas where threats may be more concerning, without pinpointing which exact input has escalated the threat score, providing some anonymity for individual pilots and not leading them to fixate on one specific area.

The utility of this program extends beyond mere identification; it actively encourages pilot engagement by providing an opportunity to acknowledge potential threat categories. This feature aims to underscore categories or data points that could heighten risk if the threat is not identified and addressed. A required digital acknowledgment could make the process compulsory. This structure is a tool to enhance communication among crewmembers, systematically ensuring a comprehensive threat forward briefing.

Structured Briefings

Establishing a specific structured briefing represents a paradigm shift in preflight preparations, leveraging technology to integrate data-driven insights. By facilitating a proactive discussion of threats, this methodology underscores the importance of communication in mitigating risk.

This approach incentivizes pilots to actively engage with the data. The following are four distinct and crucial benefits of this proposal.

- Facilitating Targeted Communication: By gathering critical data points into a threat score, pilots are equipped with a concise, real-time overview of potential threats without unnecessarily narrowing their focus. This clarity can foster more focused and productive discussions between crewmembers, as they can quickly understand and address specific areas of concern. The threat score acts as a common language, reducing ambiguity and enhancing the efficiency of briefings.

- Enhancing Situational Awareness: The inclusion of pilot data, such as total flight hours, recency of operations, and familiarity with specific aircraft or airports, directly contributes to a nuanced understanding of the crew’s current collective proficiency and potential vulnerabilities. This awareness allows pilots to adapt their communication and operational strategies to mitigate team risks more effectively.

- Strengthening Crew Collaboration: Understanding the crew composition, including the experience level of each pilot and their history of flying together, can improve interpersonal dynamics and collaboration. Awareness of potential “green on green” scenarios, in which both pilots might be new to their positions or to the aircraft, prompts a more deliberate approach to communication and support during flights.

- Mitigating Interpersonal Barriers: Operationalizing effective CRM behaviors becomes more feasible with a clear understanding of the current threat landscape. The potential threat score will serve to direct conversation to specific risks, which might otherwise be hindered by interpersonal barriers. This approach enables a more open and effective exchange of information.

Real-Time Insights

The current limitations of briefings — characterized by a lack of data, diminished engagement, and self-silencing — points to the need for a comprehensive strategy combining the use of data while fostering psychological safety and open communication. The proposed preliminary threat score model amalgamates data from diverse sources to provide pilots with real-time insights into potential threats and represents a significant step forward. It not only facilitates targeted communication and enhances situational awareness but also promotes proactive threat identification, encourages continuous learning and adaptation, strengthens crew collaboration, and helps break down interpersonal barriers.

The paradigm shift toward integrating data-driven insights into pre-departure trip kits represents a crucial advancement in aviation safety. By incentivizing pilots to engage with data through structured discussions, this approach addresses challenges related to information scarcity and lack of engagement. It is beyond the scope of this paper to resolve the self-silencing concern; however, ample academic research has been conducted on the topic previously.3

The envisioned potential threat score model offers a transformative approach to bolstering aviation safety. By harnessing targeted communication, heightened situational awareness, cohesive crew collaboration, and eliminating interpersonal barriers, this model utilizes existing data to fortify risk mitigation strategies. Positioned within our data-centric era, it represents a pivotal advancement in operationalizing and systematizing threat forward briefings, transcending reliance on individual pilot compliance to forge a solution aimed at collective vigilance and resilience.

Image: Yakobchuk Viacheslav / Shutterstock.com

Kimberly Perkins, Ph.D., is a human factors specialist whose doctoral research focused on enhancing safety by optimizing risk mitigation in sociotechnical systems; she is also an airline pilot flying the Boeing 787. Bobbi Wells is vice president, Inflight Operations and Administration, at American Airlines and chair of the Flight Safety Foundation Board of Governors.

Notes

- The United Parcel Service Airbus A300-600 crashed Aug. 14, 2013, around 0447 local time during a localizer nonprecision approach to Birmingham (Alabama, U.S.) Shuttlesworth International Airport. Both pilots were killed, and the airplane was destroyed by the impact and resulting fire. In its final report on the accident, the NTSB said the probable cause was the flight crew’s “continuation of an unstabilized approach and their failure to monitor the aircraft’s altitude during the approach, which led to an inadvertent descent below the minimum approach altitude and subsequently into terrain.” Among the report’s 15 recommendations to the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration was one calling on the FAA to “require principal operations inspectors to ensure that operators with flight crews performing [Federal Aviation Regulations] Part 121, 135, and 91 Subpart K overnight operations brief the threat of fatigue before each departure, particularly those occurring during the window of circadian low.”

- Academic research found that 75.8 percent of pilots participate in muted safety voice every year because of a negative tone established by the captain. Research also found that 57.3 percent of pilots feel silenced after bringing up a safety concern when the flight deck lacks psychological safety. Full academic findings can be found here: Perkins, K.; Ghosh, S.; Vera, J.; Aragon, C., Hyland, A. “The Persistence of Safety Silence: How Flight Deck Microcultures Influence the Efficacy of Crew Resource Management.” International Journal of Aviation, Aeronautics, and Aerospace Volume 9 (Issue 3, 2022).

- For example: 1) Perkins, K.; Ghosh, S.; Vera, J.; Aragon, C.; Hyland, A. “The Persistence of Safety Silence: How Flight Deck Microcultures Influence the Efficacy of Crew Resource Management.” International Journal of Aviation, Aeronautics, and Aerospace Volume 9 (Issue 3, 2022). 2) Perkins, K.; Ghosh, S.; Hall, C. “Interpersonal Skills in a Sociotechnical System: A Training Gap in Flight Decks.” Journal of Aviation/Aerospace Education & Research, Volume 33 (Issue 2, 2024). 3) Noort, M.C.; Reader, T. W.; Gillespie, A. “Safety Voice and Safety Listening During Aviation Accidents: Cockpit Voice Recordings Reveal That Speaking Up to Power Is Not Enough.” Safety Science Volume 139 (Issue 4, 2021). Perkins, K. (2023). “Psychological Safety on the Flight Deck.” AeroSafety World, Aug. 29, 2023. . 5) Bienefeld, N.; Grote, G. (2014). “Speaking Up in ad hoc Multiteam Systems: Individual-Level Effects of Psychological Safety, Status, and Leadership Within and Across Teams.” European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology Volume 23 (Issue 6, 2014): 930–945.