Several factors have prompted principal maintenance inspectors in the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) to avoid precipitous enforcement action against air carriers, such as grounding an aircraft fleet, if alternative corrective action resolves the safety issue. According to Keith Frable, FAA principal maintenance inspector for United Airlines, risk-based decision making, is being introduced as “a new way forward … a new path where we are not inconveniencing passengers but we’re still having continual operational safety at the airlines,” he said. Frable spoke in April at the World Aviation Training Conference and Tradeshow (WATS 2015) in Orlando, Florida, U.S.

The policy shift considered poor decisions about grounding airline fleets1 based on non-risk-related practices, reductions in the number of FAA maintenance inspectors, reductions in the number of maintenance professionals at airlines, and the numbers of new maintenance engineers added in the context of required qualifications and employee turnover. “It was an initiative about a year and a half ago to get a team together and start this process; however, the training [for some categories of inspectors] is not out yet,” he said in April.

Risk-based decision making involves FAA flight standards district offices, principal maintenance inspectors and their ongoing relationship with the airline counterparts that they oversee. This means airline maintenance leaders and maintenance technicians — as representatives of the regulated entity — will play an important role in adjusting local safety cultures, in communicating and in providing information that enables the newer process to work as intended, he said.

Prescriptive Culture

Before being hired to oversee airline maintenance operations under Federal Aviation Regulations (FARs) Part 121, FAA maintenance inspectors had been indoctrinated for years in prescriptive system safety. “We teach the regulations [under that philosophy]. We teach people to follow the regulations. … We teach people to follow a prescribed procedure in the aircraft maintenance manual. … We teach people to follow the airworthiness directive [AD]. … We teach people to follow the checklists and to stick to prescriptive language. … This culture of … adherence to rules and regulations was developed way before [most of today’s aviation safety inspectors, with average age in their 50s and 60s, were hired],” he said.

Frable’s presentation objective, he noted, was explaining “why risk-based decision making is so new for Flight Standards and why [it is] such a struggle to change the culture of Flight Standards. … This is very foreign to [principal operations inspectors] to be able to make those decisions of not grounding an airplane because an airworthiness directive isn’t accomplished on an airplane. Their initial reaction is ground it, then fix it, then fly it.”

To launch the process while training catches up with policy, Frable made other requests of the attendees. “As an operator, you can also provide risk-based analysis to your [principal maintenance inspectors]. … You need to be in the forefront … I told United [Airlines], ‘It’s your operation. You have the problem. … You operate the airplanes. Tell me the risk analysis you performed, the SMS [safety management system] process you used, what the initial risk assessment is [and] what the mitigations are going to be. … We don’t always know [at FAA] the proper mitigation and then what’s going to be the [post-mitigation action].”

Principal maintenance inspectors need all the relevant information to determine what the level of risk would be in continuing to operate affected airplanes, whether flight operations should be shut down and whether FAA and the operator need to put fixes in place right away, he said, noting that FARs Part 135, commuter and on-demand operations, and Part 145 repair stations, are not required to have a safety management system (SMS) but stand to benefit from incorporating SMS components into their operations.

“The better you get [with SMS,] the better you’re going to help the FAA inspector help you make … sound decisions based on identified risk. … If you come up with a risk-based decision [and] a risk-based mitigation, you have to stick to that plan,” Frable said. “You’ll want to make that decision based on the likelihood and severity of the event, and what that really means to your company.”

Gradual Implementation

Frable said this cultural shift will take time and experience, as well as training of FAA principal maintenance inspectors. “[The question now is,] ‘How can we get them past initial reactions to violate you [i.e., to allege airline noncompliance with a regulation or a requirement] or to ground your airplanes without having severe consequences to the flying public and to your operation?’ … How do we get in there and change the way they think about this entire process?”

Examples of how the process works — as part of Flight Standards’ transition from the Air Transportation Oversight System to the Safety Assurance System (SAS) of risk-based analysis — were taken from real-life stories of FAA experiences at United Airlines, “where we’ve worked through these issues and they’ve let me release this information … because it was done in a methodical, thorough process,” he said.

“For the Part 135 inspector and the Part 145 inspector, it incorporates decisions based on risk, so they have to go out and do their inspection, bring that data back and then decide what implications that has on the operation of your fleet or in the operation of your certificate. There’s no training for them on that, so it’s a … very big gap.”

Thrust Reverser Example

Regarding the FAA–United Airlines relationship while implementing risk-based decision making, Frable said, “We have [real-time] feedback, we have meetings. [We ask,] ‘Where are we on the project?’ if they put a mitigation in place. ‘Are we seeing the event [recur]? Has [your] mitigation worked?’” (See “Nonpunitive Interviews Yield Insights Into Aircraft Ground Damage.”)

The new process came into sharp focus in the case of noncompliance with an AD concerning thrust reversers. The stated intent in the AD was to prevent a thrust reverser from deploying in flight, he said, and the wording of the intent itself implied high risk.

Frable said, “They didn’t perform an AD task, so their initial conversation was, ‘We missed the AD cycle on these airplanes because the [task] card wasn’t done, whatever the reason. And now we have airplanes flying out there with the potential of a thrust reverser opening up in flight because we didn’t accomplish the AD.’”

He said that, historically, a principal maintenance inspector’s immediate reaction likely would be to say, “Let’s shut down 85 airplanes around the world, inconvenience passengers and shut the operation down until we get that checked out.”

In the risk-based decision making paradigm, inspectors make a more cautious and deliberate assessment first. In the example, United Airlines brought a sound decision to the discussion derived from detailed analysis of the thrust reverser situation, he said.

“The [uncompleted] task was an ancillary task; it wasn’t part of the AD. It was a task that was done on a secondary backup system that had a 4,000-hour flight-cycle check [interval] on it. … Where’s the criticality on a 4,000-hour check? [It’s] pretty minor. [The maintenance task is not done] to prevent the [in-flight thrust reverser deployment]. It is there as a backup check. You [check] a pin [on a circuit board and] make sure [you don’t] have voltage at a certain spot. … Even if voltage is there, it wouldn’t contribute to what the AD was for.”

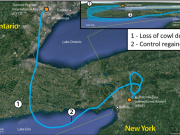

Instead of grounding aircraft, FAA permitted a staged-but-rapid assessment of the risk factors by United Airlines, starting on a Friday night with four airplanes already in “remain overnight” status, including one in a hangar for a heavy maintenance check.

“If on Saturday [morning,] those four airplanes had voltage [present and so] met the … required-maintenance [criteria], then … this would raise the likelihood and, in my opinion, raise the severity. That would tell me that [United Airlines] needed to do more of those checks quicker,” Frable said. “On Saturday morning, all four checked out ‘good.’ On Sunday, they [planned to check] another 10 [but instead of continuing checks for four to five days], all were checked [in three days, which brought them into AD compliance]. … Our risk assessment was valid, and we proved it was valid. There was no risk to the flying public, and there was no risk that [noncompliance with] this AD was going to cause the catastrophic loss of an airplane.”

A similar situation at United Airlines occurred when FAA inspectors discovered that a manufacturer of auxiliary power units (APUs) had discontinued a process called the third bearing wash. FAA’s immediate theoretical concern was that, potentially, this practice could have a life-limiting effect on bearings — essentially a type of damage that could lead to bearing failure and an uncontained failure of the APU.

“[We found] out that that the third bearing wash was required as a result of a [another manufacturer’s] maintenance task card vetted by United Airlines,” and apparently APUs were being returned to line service without the benefit of this process, although still specified in the aircraft maintenance manual. Frable worked with United Airlines engineers to check for bearing discrepancies and to rate the risk based on checking bearings from a sample of APUs.

The engineers’ report at the end of this work led to a risk-based decision that potential severity was high but that probability of an unsafe outcome was extremely remote. Frable ruled that no grounding would be required, and further analysis justified the risk-based decision making. The engineers ultimately concluded that performance or nonperformance of the third bearing wash actually had no effect on safety, and that ironically, all the APUs of initial concern were in maintenance parts stores at the time. “We could have grounded airplanes. We could have made that decision based on a knee-jerk reaction,” Frable said.

Hangar Nose Drop

Another event raised similar initial concerns of potentially catastrophic outcome. In this case, Frable received a late-night message saying that the nose of a United Airlines aircraft had dropped to the hangar floor during maintenance. No one was injured or killed in this ground accident. “So again … you don’t shut everything down. You let the company work the process. The airplane is safe. It’s in the hangar,” Frable said. He visited the site to observe whether the nose gear safety pins had been inserted, and assisted otherwise in the airline’s investigation the next morning.

“[Critics] could say, ‘You’re letting them fly around with AD noncompliances. You’re letting them drop airplanes on the nose, and you’re not shutting them down. You’re not stopping [their investigation] process. You could say that, but in reality — if you have decisions based on risk and you have a great relationship — [this] is going to help [the airline] and it is going to help the FAA make those calls. [Airlines still] do get violated [but] that’s the last thing we want to do. As a [principal maintenance inspector], am I going to violate the company [because an airplane was dropped on the nose]? Typically, I’d say no,” he said.

“If you put a different person in the same position, would they make the same mistake? If the answer is ‘no,’ the procedures are there, the task cards are written properly, the requirement to pin the nose gear when [the airplane] comes into the hangar is there. … The company has established a protocol, everything is there. …

“So you go to the individual who made a conscious decision not to follow the procedures set forth by the company. I want [the airline] to fix the guy who was not following them … to fix that culture. I don’t want [them] to fix what’s already in place and what’s already working. … We have an ASAP [aviation safety action program, and this situation] would be handled through ASAP.”

Ultimately, post-mitigation analysis by the airline is critical in all such situations, he said. “Did it work? Was it effective? What were the lessons learned? Is there something else we should have done for that event? … If it wasn’t a good, comprehensive fix and it was ineffective, how can we make it effective and what follow-up do we need to do to make that mitigation effective?” he said.

Note

- In 2008, for example, the FAA was involved in grounding of airplanes by American Airlines, Southwest Airlines and Delta Air Lines, Frable said, adding, “[Delta’s McDonnell Douglas MD-88] fleet was grounded for basically the routing of wiring in the landing gear and for [cable-sheath] tie wraps. … If you risk-rate that, was it a high risk? I would say no. The likelihood of a catastrophic event would be low and the severity would be low. … However, the decision was made based on it being [noncompliance with] an airworthiness directive and an airworthiness directive alone.”

Featured image: © Mathieu Pouliot | AirTeamImages

Engine maintenance: © Denis Roschlau | AirTeamImages