Runway/taxiway excursions were the most common commercial aviation accident type in 2017, and although none of the accidents were fatal, runway safety generally continues to be a focus of the International Air Transport Association’s (IATA) Safety and Flight Operations team, according to the recently published IATA Safety Report 2017.

IATA said there were six fatal commercial airline accidents worldwide in 2017 that resulted in the deaths of 19 passengers and crewmembers. None of the six fatal accidents involved a passenger jet. Five of the fatal accidents involved turboprop aircraft and one involved a cargo jet: the Jan. 16, 2017, crash of a MyCARGO Airlines Boeing 747-400 freighter, which killed 35 people on the ground as well as all four crewmembers.

“Globally, the 2017 fatal accident rate was the equivalent of one fatal accident for every 6.7 million flights. If we look at it another way, using fatality risk, on average, a person would have to travel by air every day for 6,033 years before experiencing an accident in which at least one passenger was killed,” IATA Director General and CEO Alexandre de Juniac said April 17 at the IATA Safety and Flight Ops Conference in Montreal shortly after the Safety Report was released.

“Yet there is room for improvement. We experienced six fatal accidents involving turboprops and cargo flights in 2017, and we’ve had three commercial airline fatal accidents1 so far this year. In addition, we had some well-publicized events in which safety margins were compromised and the outcomes could have been far worse than they were.”

IATA said there were 45 accidents overall in 2017 for an accident rate of 1.08 per 1 million flights. Seventeen of those accidents were runway/taxiway excursion accidents, including eight veer offs, eight overruns and one taxiway excursion. Six of the excursion accidents resulted in hull losses and two involved IATA member carriers.

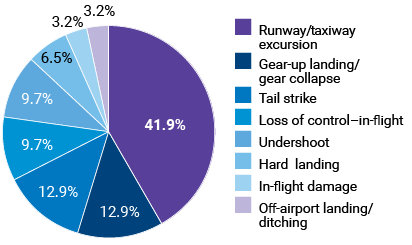

“As we review this year’s report, we see that again runway excursion is our most common accident,” Stephen Hough, chairman of the IATA Accident Classification Technical Group, said in a foreword to the report. “These often have differing contributory factors, such as manual handling, unstable approach, gear/tire failure or a combination of these. The fatality risk from these kinds of accidents is generally low, but a rate reduction in this common accident category is an area to concentrate on,” he said. Figure 1 shows the distribution of 2017 accident end states.

Figure 1 — Distribution of Accident End States, 2017

Source: International Air Tranport Association Accident Database

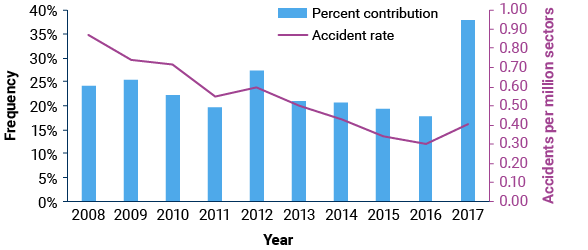

In the past five years (2013–2017) there have been 76 runway/taxiway excursion accidents with eight fatalities, according to IATA data. The majority of the accidents — 42 — occurred in either the Africa (21) or Asia/Pacific (21) regions, and 11 occurred in the Latin American/Caribbean region. Almost all of the excursions happened during takeoff, with a small handful occurring during takeoff or a rejected takeoff. Figure 2 shows percentage of all accidents over the past 10 years that were runway/taxiway excursions.

Figure 2 — Runway/Taxiway Excursions

Source: International Air Tranport Association Accident Database

In the Africa region, there were 2.99 runway excursions per 1 million sectors over the five-year period. The global runway/taxiway excursion rate for the period was 0.39 per 1 million sectors. North America had the lowest rate at 0.10 per million sectors, followed by North Asia and Europe, both at 0.17. All the other regions had excursion rates greater than the global rate.

IATA uses a threat and error management (TEM) framework to identify the top factors contributing to various types of accidents. It breaks down the contributing factors into several categories, including latent conditions, which are conditions present in the system before the accident, made evident by triggering factors. These often are related to deficiencies in organizational processes and procedures. A threat is defined as an event or error that occurs outside the influence of the flight crew, but that requires flight crew attention and management to maintain safety margins. A flight crew error is an observed flight crew deviation from organizational expectations or crew intentions. An undesired aircraft state (UAS) is a flight crew–induced state that clearly reduces safety margins or is a safety compromising situation that results from ineffective TEM. An end state is a reportable event. The difference between end state and UAS is that UAS is recoverable but an end state is not.

IATA analysis shows that deficient regulatory oversight by the state, which is categorized as a latent condition, was a top contributing factor in 45 percent of excursion accidents over the past five years for which there is enough information to make such a determination. Accidents for which there is not sufficient information are excluded from this analysis. Meteorology, which is categorized as a threat and covers thunderstorms, poor visibility/instrument meteorological conditions, wind shear and wind-related issues, icing conditions and hail, also was a top factor in 45 percent of the excursion accidents. Long, floated, bounced, firm, off-center or crabbed landing was a factor in 43 percent, and manual handling/flight control errors were a factor in 38 percent.

In reviewing the 2017 accidents recorded in its accident database and coded by the Aircraft Classification Technical Group, IATA said the top threats encountered by aircraft involved in runway safety events were environmental factors, specifically wind shear and gusty conditions, which counted as a threat in 18 percent of the recorded accidents. Second in importance were issues with airport markings and signage, optical illusions or visual misperception.

The most common errors that contributed to runway safety events last year involved manual handling and incorrect flight control inputs. These errors were apparent in 30 percent of the cases. Unintentional noncompliance with standard operating procedures and/or cross-verification contributed to 15 percent of the accidents, and failure to go around following an unstable approach was a contributing factor in 9 percent of the accidents.

In the Safety Report 2017, IATA made numerous recommendations regarding possible countermeasures and prevention strategies. The countermeasures generally were aimed at two levels: the operator or state responsible for oversight and the flight crew.

IATA’s runway/taxiway excursion–related recommendations to operators included training flight crews to go around from a long/floated/bounced/firm/off-center/crabbed landing; implementing a go-around policy; training flight crews to monitor and make effective call outs; defining the touchdown aiming point as the target; and using a flight operational quality assurance program to monitor compliance and reinforce a go-around policy and to monitor long landings.

Among the recommendations made to regulators and industry were encouraging implementation of a safety management system for all airlines; encouraging a policy of rejected landing in the case of long landings; requiring training in bounced landing recovery techniques and reviewing the International Civil Aviation Organization’s Global Runway Safety Action Plan, released in November, which identifies stakeholder mitigations to runway safety issues.

Notes

- In the weeks since de Juniac’s remarks, there have been two more fatal commercial passenger jet accidents: On April 17, a passenger on a Southwest Airlines flight in the United States died from injuries suffered in an in-flight uncontained engine failure; and on May 18, 112 people died in the crash shortly after takeoff from Havana of a Boeing 737-200 being operated on behalf of Cubana de Aviación. Both accidents are still under investigation.