Concerned by the pilot’s “reckless and irresponsible” maneuvers during a March 12, 2018, approach to Kathmandu, Nepal, an air traffic controller canceled the US-Bangla Airlines Bombardier Q400’s landing clearance. Seconds later, the airplane struck the runway and burst into flames, killing 51 of the 71 passengers and crew.

The Nepal Accident Investigation Commission, in its final report, said the probable cause of the crash was “disorientation and a complete loss of situational awareness in the part of crewmember.”

Among the contributing factors was the airplane’s position, “offset to the proper approach path, that led to maneuvers in a very dangerous and unsafe attitude to align with the runway,” the report said. “Landing was completed in a sheer desperation after sighting the runway at very close proximity and very low altitude.”

The report noted that, although a go-around would have been possible “until the last instant before touchdown,” the crew made no attempt to reject the approach and try again.

‘High Levels of Stress’

The flight to Tribhuvan International Airport in Kathmandu began with departure at 0651 UTC from Hazrat Shahjalal International Airport in Dhaka, Bangladesh. The accident report noted that analysis of the cockpit voice recorder (CVR) indicated that, during pre-takeoff communications with a Dhaka ground controller, the captain’s “changes in vocal pitch and language used indicated that he was agitated and experiencing high levels of stress.”

During climb, the captain (the pilot-in-command [PIC]) overheard a controller’s communication with another US-Bangla airplane and, “without verifying whether the message was meant for him … engaged in some unnecessary conversation with the operations staff.” Again, the report said, the CVR recording indicated that the captain was “very much emotionally disturbed and experiencing [a] high level of stress.”

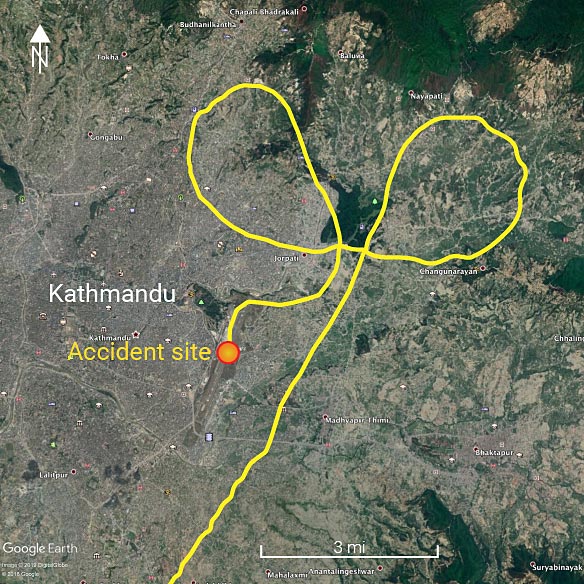

As the airplane neared Kathmandu, both pilots forgot to cancel a previously assigned, and then superseded, hold on the flight management system “as they were engaged in some unnecessary conversation,” the report said. Minutes later, after deviating to the right of the final approach path on the VOR (VHF omnidirectional radio) approach to Runway 02, the captain reaffirmed to an airport tower controller that the crew still planned to land on Runway 02; nevertheless, the airplane continued to the right, toward Runway 20.

As the airplane neared Kathmandu, both pilots forgot to cancel a previously assigned, and then superseded, hold on the flight management system “as they were engaged in some unnecessary conversation,” the report said. Minutes later, after deviating to the right of the final approach path on the VOR (VHF omnidirectional radio) approach to Runway 02, the captain reaffirmed to an airport tower controller that the crew still planned to land on Runway 02; nevertheless, the airplane continued to the right, toward Runway 20.

With the crew “struggling to find the runway” and the enhanced ground-proximity warning system (EGPWS) emitting multiple alerts and warnings, the airplane descended as low as 175 ft above the ground at bank angles of as much as 40 degrees, the report said, adding that accident investigators concluded that, at this point, “there was a complete loss of situational awareness on the part of the flight crew.”

A controller cleared the flight to enter a right downwind for Runway 02, along with instructions

to remain clear of the runway while another airplane landed.

Instead of entering the traffic pattern, however, the accident airplane continued toward Runway 20, climbing to 6,500 ft as the captain “started maneuvering the aircraft on a steep right-hand orbit … admitting to the FO [first officer] that he had made a mistake as he was constantly talking to her,” the report said.

During the turn, the airplane was banked at angles up to 45 degrees, and its descent rate climbed about 2,000 fpm, triggering EGPWS warnings. The CVR recorded a pilot on the ground telling air traffic control (ATC) that the pilots of the accident airplane “seemed to have been disoriented and lost.”

Soon afterward, the crew sighted the runway, and the captain began “desperate maneuvers in an attempt to put the aircraft on the ground” and, at 0832, requested and received clearance to land.

At 0833, when a tower controller observed the airplane maneuvering near the ground and not aligned with the runway, he became “alarmed by the situation” and “hurriedly canceled the landing clearance.”

Within seconds, the report added, “the aircraft pulled up in westerly direction and, with very high bank angle, turned left and flew over the western area of the domestic apron.” It continued on a southeasterly heading toward the airport traffic control tower as controllers “ducked down … out of fear that the aircraft may hit the tower building.”

The airplane touched down 1,700 m (5,578 ft) past the threshold of Runway 20 and veered off the runway and through the perimeter fence, stopping 442 m (1,450 ft) southeast of the runway. It was destroyed by the impact and the subsequent fire.

Released From Air Force

The 52-year-old captain had an air transport pilot license with ratings for the Dash 8 and the ATR 72. He had accumulated 5,518 flight hours, including 1,793 hours in type, and had completed his most recent proficiency check less than one month before the accident.

He was described by colleagues as “very friendly, soft spoken and gentle,” “level headed” and well-liked. They considered him a good teacher and flight instructor.

He had been released from the Bangladesh air force in 1993 because of depression and then “briefly” flew cargo airplanes, the report said. He was declared fit to fly civilian aircraft in 2002, after a detailed medical examination by a medical assessor, and later flew for two Bangladeshi airlines before joining US-Bangla in 2015, eventually becoming a designated check pilot for the Q400.

The examiner who conducted his most recent annual medical evaluation found him free of any symptoms of depression. Accident investigators also reviewed his medical records from 2012 to 2017 and found no mention of depression; in each of those years, the examiner cleared him for flight duties. Toxicology tests did not check for prescription medications that typically are used to treat depression.

Although the CVR recording indicated that the captain had smoked during the flight, medical records showed that he had not disclosed in his self-declaration form that he used tobacco, declaring at different times that he had never smoked and that he had once smoked but had quit in 2010. His depression diagnosis also was not mentioned “in most of [his] annual medical self-declaration form[s],” the report said, adding, “This shows that there is no consistency in self-declaration regarding actual history and real habit.”

The co-pilot, 25, had a commercial pilot license, and the accident report said she had ratings in the Dash 8 and Cessna 152. Her most recent proficiency check was in January 2017. She joined US-Bangla as a first officer in September 2016. She completed her flight training “with good grades,” the report said, and she demonstrated “great respect to seniors.” The accident flight was her first flight to Kathmandu as a crewmember, and “she showed utmost interest to learn.”

However, her inexperience and the steep power gradient — with her experience level far below the captain’s — “probably disallowed FO from being assertive, even though she was effectively monitoring the progress of the flight and suggested/initiated corrective actions.”

The airplane, manufactured in 2001, had accumulated 21,419 airframe hours and had been operated since 2014 by US-Bangla Airlines. It had two Pratt & Whitney Canada PW150A engines; the left engine had 22,431 hours since new and 6,778 hours since its most recent overhaul while the right engine had 21,993 hours since new and 9,654 hours since its last overhaul.

The airplane, manufactured in 2001, had accumulated 21,419 airframe hours and had been operated since 2014 by US-Bangla Airlines. It had two Pratt & Whitney Canada PW150A engines; the left engine had 22,431 hours since new and 6,778 hours since its most recent overhaul while the right engine had 21,993 hours since new and 9,654 hours since its last overhaul.

Aircraft maintenance had been performed in compliance with a maintenance control manual that had been approved by the Civil Aviation Authority of Bangladesh (CAAB), with the most recent maintenance an A-check on March 9, 2018.

Weather conditions at the time of the crash included scattered low clouds and a few cumulonimbus clouds to the south, with winds from the west at 7 to 8 kt and visibility of 6 to 7 km (10 to 11 mi).

The report said that US-Bangla Airlines was in compliance with CAAB policies and standards, that safety reporting procedures were well-established and that preflight briefings were standard procedures, to be conducted before every flight.

However, a recently introduced requirement calling for international flights departing from Bangladesh to obtain air defense clearance (ADC) before departure “took longer to circulate among the crew” than expected, and the captain was unaware of the change, the report said. The dispatcher’s preflight briefing did not include the required Bangladesh ADC number, and when Dhaka ATC requested the flight’s ADC number, he could not provide it.

‘One-Way Conversation’

The Accident Investigation Commission focused its analysis on the captain’s state of mind, noting that as the pilots prepared for the approach to Kathmandu, he was not only the pilot flying but also an instructor, explaining the operating environment in Kathmandu and other aspects of the flight “with great passion, calmness and professional efficiency.”

He asked the first officer if she was comfortable with what he had explained, and the report said that the commission “believes that the PIC was constantly trying to prove his professionalism and reputation as a competent trainer in front of a junior trainee.”

Many of his comments, however, dealt with a colleague’s criticism of his competency, the report said.

“CVR record showed that the PIC was talking almost nonstop throughout the duration of flight, with FO being patient listener most of the times,” the report said. “Most of the conversation in the cockpit was directed towards and aimed at the female colleague, who apparently was telling others that the PIC was not a good instructor. … This talk seemed to hurt the PIC very deeply, as he really took pride in his teaching skills. He was telling the FO about how this particular talk going around had hurt him a lot, so much so that, though he loved the company and liked the environment around, … he would give notice for resignation … because of the alleged behavior of the female colleague.”

His stress level was obvious, the report said, noting that at times during the flight, he was irritable, tense, moody and aggressive. The report suggested that his stress might have led him to smoke in the cockpit during the flight — an activity that “clearly is against the company standard operating procedure.”

The report said that the captain’s “state of mind, with high degree of stress and emotional state, might have led him to all the procedural lapses,” including his failure to complete the before landing checklist and his repeated “obsessive” requests for the landing checklist,” and might have resulted in the unstabilized approach with the approach airspeed not under control, the airplane not fully configured, the checklists not completed and the failure to initiate a go-around.

‘Lack of Assertiveness’

The report concluded that controllers in the airport traffic control tower had “tried their best” to aid the flight crew, directing other aircraft away from the Q400 and making both runways available for landing. Nevertheless, the report cited ATC actions in three of the 20 factors identified as contributing to the accident:

- The “lack of assertiveness” by one tower controller in monitoring the airplane’s flight path and failing to issue clear instructions to conduct a standard missed approach;

- The “lack of clear understanding and acknowledgment on the part of both ATC and the crew” of communications regarding the landing runway; and,

- The failure of ATC to alert the crew to the airplane’s actual position.

- The report also singled out the operator’s failure to provide simulator training for the visual approach to Runway 20 for the crew, especially for the captain.

The investigation resulted in issuance of 15 safety recommendations, including a recommendation that the CAAB require pilots who have been permanently grounded for medical reasons to undergo thorough physical and psychological assessments before their licenses are renewed and to have the medical condition monitored during subsequent aeromedical examinations.

A second recommendation to the CAAB said that airline pilots should undergo psychological evaluations as part of their training or before being hired.

Eleven recommendations to US-Bangla included calls for the airline to “establish an effective mechanism to monitor and assess mental status of the crew” and to implement a policy that would remove from flight rosters “any crewmember found to be stressed, fatigued or emotionally disturbed.” Recommendations also said the airline should emphasize crew resource management and compliance with standard operating procedures and should reinforce its existing ban on smoking in the cockpit.

The report recommended that the Civil Aviation Authority of Nepal enhance ATC training to ensure that controllers “become more assertive when handling the traffic and issuing clearances … especially in the event of the abnormal or emergency situations.”

This article is based on Final Report on the Accident Investigation of US Bangla Airlines, Bombardier (UBG-211), DHC-8-402, S2-AGU, at Tribhuvan International Airport, Kathmandu, Nepal, on 12 March 2018. Approved Jan. 27, 2019.

Featured image: Magar Sanday | Pxhere CC0

Flight path: path source, Nepal Ministry of Culture, Tourism and Civil Aviation; base image: Google Earth

Accident image: Nepal Ministry of Culture, Tourism and Civil Aviation

Accident aircraft: Shadman Samee | Wikimedia CC-BY-SA 2.0