Runway safety-related events, which the International Civil Aviation Organization has identified as one of three high-risk accident occurrence categories, are the focus of numerous government and industry mitigation efforts, but occurrences continue to vex aviation stakeholders across different industry sectors, according to presenters at two recent Flight Safety Foundation events and to data available from a variety of sources.

The most common types of runway-related events are runway incursions and excursions. In its online Runway Excursions Support Tool, the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) uses the Civil Air Navigation Services Organization (CANSO) definition of an excursion: an event in which an aircraft veers off or overruns the runway surface during either takeoff or landing. FAA says that runway excursions lead to more runway accidents than all other causes combined.

The European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) uses a common European Risk Classification Scheme (ERCS) to classify the risk of all occurrences reported to European authorities. The main purpose of the risk score is to discriminate between the occurrences with a higher and lower associated risk. In EASA’s Annual Safety Review 2018, runway excursions are shown to have greater high-risk occurrence frequency and a higher aggregated ERCS score than runway incursions.

The International Air Transport Association (IATA) Safety Report 2018 indicates that there were 15 commercial aviation runway/taxiway excursion accidents in in 2018. For the 2014–2018 period, there were 15 excursion accidents, with most happening during the landing phase of flight. There were no runway collision accidents in commercial aviation last year and 10 in 2014–2018, IATA data show.

Logan Jones, a runway safety specialist with Airbus subsidiary NAVBLUE, said at Flight Safety Foundation’s Singapore Aviation Safety Seminar (SASS 2019) in March that after several years of decline, the number of excursions increased in 2017. “The issue is still there. This is not the time to pat ourselves on the back,” he said.

Jones also cautioned that while the various annual reports focus on accidents, there are many more small excursion events that do not end in a crash. “We need to focus on more than just major accidents,” he said.

Factors that may cause or contribute to an excursion include runway contamination, adverse weather conditions, mechanical failure, pilot error and unstable approaches, according to FAA and CANSO documentation.

Both Airbus and Boeing are developing and offering systems and tools on their aircraft that are intended to prevent runway overruns on landing by providing pilots with enhanced situation awareness and, in some cases, error detection.

Jones said that closing the loop on runway safety requires pilots to effectively prepare for the approach to landing, to use the appropriate tools to maintain situational awareness and to be alerted when something is wrong, and to provide feedback on the landing and runway conditions, if necessary, to aid the decision making of air traffic controllers and following pilots.

Bob Aaron, senior safety pilot, Flight Technical and Safety, Boeing, stressed the need for pilots to be properly trained on all such systems and to use the systems as they are intended. “Manufacturers see the same reasons for excursions time and time again,” he said. “We know why we’re having excursions,” but have a difficult time getting pilots to cooperate.

FAA offers the following advice to pilots to mitigate the risk of runway excursions:

- Maintain a mental picture of the required descent profile;

- Advise air traffic control (ATC) as soon as possible if descent is required or additional track miles are needed to execute a stable approach;

- Be aware of published local ATC procedures/airspace restrictions that impact the approach;

- Make requests for operational requirements, not for convenience;

- If you can’t comply with an instruction, let ATC know early;

- Be predictable;

- When departing, and before accepting a clearance to enter the runway, tell ATC if you’re likely to need additional time on the runway; and,

- In an emergency situation, let ATC know as soon as is practicable.

For controllers, FAA offers the following advice:

- Fly the arrival/approach procedure as published;

- Avoid routine vectoring;

- When vectoring aircraft, provide track miles to the airport;

- Keep the pilot informed of ATC intentions;

- Ensure the runway is appropriate for the wind;

- Issue accurate and timely information;

- Apply appropriate speed-control restrictions;

- Avoid close-in runway changes, even to a parallel runway; and,

- Avoid combining a descent and speed reduction.

Runway Incursions

Runway incursions are defined by FAA as “any occurrence at an aerodrome involving the incorrect presence of an aircraft, vehicle or person on the protected area of a surface designated for the landing and takeoff of aircraft.” In Appendix 1 to its Pilot’s Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge (PHAK), FAA said that an average of three runway incursions occur daily at towered airports in the United States, and that incursions involve commercial, general aviation (GA) and military aircraft, as well as pedestrians and surface vehicles. The PHAK also says that incursions are a serious safety concern and have the potential to cause significant damage to both persons and property.

In fiscal year 2018, which ended Sept. 30, 2018, there were 1,832 reported runway incursions in the United States, an increase of 4.8 percent from fiscal 2018, when there were 1,748 reported incursions, according to FAA data.

Approximately 62 percent, or 1,142, of the incursions in fiscal 2018 were attributed to pilot deviations from procedures, such as crossing a runway hold marker without clearance from ATC, taking off without clearance or landing without clearance. FAA says that three-quarters of incursions caused by pilots are attributable to GA pilots. The most common causal factors are failure to comply with ATC instructions, lack of airport familiarity and nonconformance with standard operating procedures.

Nearly 19 percent, or 345, of the incursions were categorized as operational incidents involving ATC, such as controllers clearing an aircraft onto a runway while another aircraft is landing on that runway or issuing a takeoff clearance while the runway is occupied by another aircraft or vehicle. Vehicle or pedestrian incursions, such as when a vehicle crosses a runway hold marking without ATC clearance, comprised a similar number of incursions in fiscal 2018, according to FAA.

FAA categorizes runway incursions by severity. Category A and B events are the most serious, with Category A, defined as a serious incident in which a collision was narrowly avoided, being the last step before an accident.

Michael Watkins, FAA’s senior air traffic representative–Asia Pacific, speaking at SASS 2019, said the overall incursion rate is less than three per 100,000 operations and that very few accidents occur as a result of incursions. In his remarks, he stressed the importance of organizations promoting a reporting culture because “to track incursions you’ve got to have a culture that reports it.”

NAVBLUE’s Jones said that in an average year, there are 450 Category A/B runway incursions and more than 5,000 less serious incursions. Jones’ data was drawn from a larger pool and included European data as well as FAA data.

Wrong-Surface Events

FAA, which has identified reducing the risk of wrong-surface events as one of its top priorities, defines a wrong-surface event as occurring when an aircraft lands or departs, or tries to land or depart, on the wrong runway or on a taxiway. The definition also includes when an aircraft lands, or tries to land, at the wrong airport.

On average, aircraft land on the wrong surface at airports in the United States twice a week, and these landings present risks that can lead to catastrophic events, according to Watkins. The total number of wrong-surface events across the National Airspace System (NAS) is much higher.

“This happens more than you want to know,” said Steven Hansen, chairman of the National Air Traffic Controllers Association’s (NATCA) National Safety Committee. In a presentation at the Foundation’s 64th Business Aviation Safety Summit (BASS 2019) in Denver in early May, Hansen said that from fiscal 2016 to fiscal 2018, there were 557 wrong-surface landing/approach events in the NAS and 464 wrong-surface departure events.

Hansen said that 85 percent of the wrong surface landing/approach events involved GA aircraft; that 89 percent occurred during daylight hours and that 91 percent occurred with a visibility of 3 mi (5 km) or greater. During the period, 63 facilities experienced three or more of these types of events, he said. The data are similar for wrong-surface departure events, with the bulk of the events involving GA aircraft operating during daylight hours.

Hansen also said that the majority of events happen at mid-level airports and smaller; he used Raleigh, North Carolina, and San Antonio, Texas, as examples of mid-level airports that are more likely to be used by GA aircraft.

Commercial carriers, however, are not immune from wrong-surface events, and Hansen said that “those commercial events are some of the riskiest, most dangerous events in the NAS.”

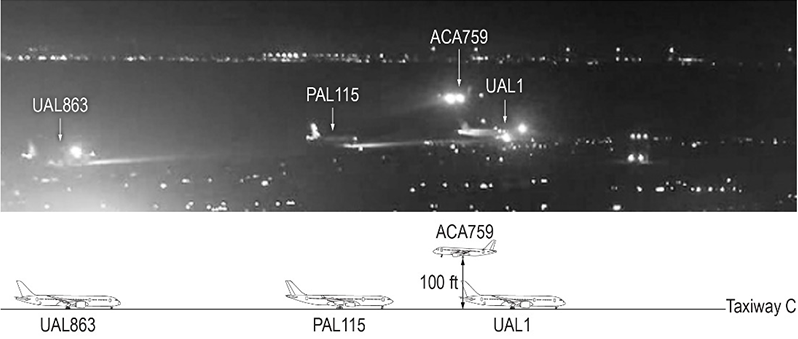

There have been several notable close calls in the past few years. Perhaps the most widely publicized occurred on July 7, 2017, when an Air Canada Airbus A320 on approach to San Francisco International Airport (SFO) just before midnight local time lined up with an occupied taxiway rather than the parallel Runway 28R, where it had been cleared to land.

The taxiway was occupied by four air carrier airplanes that were awaiting takeoff clearances. The Air Canada jet overflew the first aircraft on the taxiway at an altitude of 100 ft. Seconds later, the Air Canada pilots initiated a go-around. The A320 overflew the second airplane at an altitude of about 60 ft.

The U.S. National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) cited as the probable cause of the incident the crew’s “misidentification of Taxiway C as the intended landing runway, which resulted from the crewmembers’ lack of awareness of the parallel runway closure due to their ineffective review of NOTAM [Notices to Airmen] information before the flight and during the approach briefing.”

Watkins said that SFO is a “tough airport.” In addition to the Air Canada incident, SFO had three other wrong-surface events from February 2017 through January 2018.

One of the technologies deployed by FAA to reduce the potential for collisions at U.S. airports and improve runway safety is ASDE-X, which stands for airport surface detection equipment. ASDE-X enables air traffic controllers to detect potential runway conflicts by providing coverage of movement on runways and taxiways.

ASDE-X data are derived from surface movement radar, multilateration sensors, automatic dependent surveillance–broadcast sensors, the terminal automation system and aircraft transponders. By fusing the data, ASDE-X is able to determine the position and identification of aircraft and transponder-equipped vehicles on the airport movement area, as well as aircraft flying within 5 mi (8 km) of the airport, FAA said. The technology has been installed at 35 U.S. airports.

In September, FAA began testing a modification to the ASDE-X system, called taxiway arrival prediction enhancement, that would enable it to detect and issue alerts on aircraft that are lined up for the taxiways.

Featured image: © helivideo | Adobe Stock

Airplanes on runway: © Good Studio | Adobe Stock

Air Canada incident diagram: U.S. National Transportation Safety Board