Shortly after departing on a cargo flight from Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, a Swearingen Metro II abruptly dropped out of radar coverage. The last few radar “hits” indicated that the aircraft had pitched nose-down into a 30,000-fpm descent. The wreckage was found littering a mountainside. Many of the pieces had separated from the aircraft before hitting the ground.

The absence of recorded voice and flight data, and the severity of the aircraft damage, provided a challenge to investigators in determining the cause of the fatal crash. There was no sign of an aircraft malfunction, and neither the captain nor the first officer had radioed that something was amiss before the Metro began the plunge.

One critical finding emerged from toxicological tests and an autopsy of the captain: He had been drinking heavily before the flight. Alcohol intoxication obviously was a factor in the accident, but precisely how the captain’s impairment affected the flight could not be determined.

Among three possibilities proffered by the Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) was that the captain might have intentionally initiated the fatal descent. The investigation also raised the question of whether the accident was a suicidal “copycat act” mimicking the recent Germanwings crash. The Metro accident occurred on April 13, 2015 — 20 days after the extensively publicized crash of the Airbus A320 that was deliberately flown into the ground in the French Alps, killing all 150 people aboard, by the depressed and psychotic first officer.1

Performance Review Required

The Metro was being operated by Carson Air as Flight 66, a scheduled weekday cargo flight from Vancouver to Fort St. John with stops in Prince George and Dawson Creek, British Columbia.

The captain, 34, had a commercial pilot license and 2,885 flight hours, including 1,890 hours in type. He was hired by Carson Air as a Metro first officer in May 2013. (The accident report provided no details about his previous flying experience.) Shortly after he was promoted to captain in December 2014, another company pilot reported that he had to take over the controls from him. (The report provided no details about the incident.) The captain consequently was required by the company to undergo a performance review and “was assessed as effective, competent or highly effective in most evaluated categories,” the report said. “No areas of concern with his performance were identified.”

In March 2015, the captain received a “non-disciplinary” letter from Carson Air cautioning him that he was required to comply with the company’s operations manual at all times. The letter was prompted by an incident involving the improper refueling of an aircraft that resulted in the need to reduce the cargo load, the report said.

Later that month, the captain applied for the position of chief pilot for cargo operations at the company’s Vancouver base. However, Carson Air chose another pilot to fill that position.

The first officer had a commercial license and 1,430 flight hours, including 57 hours in type. (His age was not specified.) He had flown de Havilland Twin Otters and Beech King Air 350s before joining Carson Air in March 2015. “The first officer was an experienced pilot and described as a very good member of a team or flight crew,” the report said.

The aircraft, an SA226-TC Metro II built by Swearingen Aircraft in 1977, had accumulated 33,245 airframe hours. The Metro had been operated as a passenger aircraft in the United States until Carson Air purchased it in 2006 and modified it as a cargo-hauler. “Among other changes, the conversion involved the removal of all passenger seats and cabin windows, and the installation of cargo net bulkheads for securing freight,” the report said.

The aircraft, an SA226-TC Metro II built by Swearingen Aircraft in 1977, had accumulated 33,245 airframe hours. The Metro had been operated as a passenger aircraft in the United States until Carson Air purchased it in 2006 and modified it as a cargo-hauler. “Among other changes, the conversion involved the removal of all passenger seats and cabin windows, and the installation of cargo net bulkheads for securing freight,” the report said.

The Metro was one of 22 aircraft operated on contract and medical evacuation flights by Carson Air from its headquarters in Kelowna, British Columbia, and its bases in Vancouver and Calgary, Alberta. The company had 120 full-time employees.

No Abnormal Behavior Noted

The accident occurred on a Monday morning. The flight crew had been off duty the previous two days. The first officer arrived at the airport at about 0600 local time and appeared to be in good spirits, the report said. He spent about five minutes in the company’s flight-planning room before going out to the aircraft. The captain arrived at about 0615. Other pilots who talked with him in the flight-planning room said that he “appeared to be in a positive state of mind” and exhibited “no abnormal behavior,” the report said.

The aircraft departed from Vancouver International Airport at 0703 and headed north toward Prince George. Shortly after departure, the crew was cleared by a Vancouver Centre air traffic controller to climb to the flight-planned cruise altitude, 20,000 ft. The acknowledgement of the clearance by the first officer, the pilot monitoring, was the last radio transmission received from the Metro.

At the time, air traffic control (ATC) secondary surveillance radar showed that the aircraft was climbing through 8,700 ft about 4 nm (7 km) north of North Vancouver. The indicated climb rate of 1,500 fpm and the 185-kt groundspeed were normal, according to the report. Meteorological data indicated that the Metro was in instrument meteorological conditions.

‘Structural Disintegration’

ATC radar data indicated that 80 seconds after the first officer acknowledged the climb clearance (and about six minutes after departure), the aircraft pitched nose-down at about 6 degrees per second while maintaining a steady northerly track. The Metro was descending through 5,000 ft about 10 to 14 seconds later when radar contact was lost. “During that period, the aircraft’s descent rate exceeded 30,000 fpm, and aerodynamic forces caused structural disintegration of the aircraft (in-flight breakup),” the report said. “There was no mayday call or other communication from the aircraft during this period.”

The Metro’s emergency locator transmitter (ELT) activated on impact, but the ELT’s antenna had been damaged and no emergency signal was detected by the search-and-rescue satellite system. “Deteriorating weather conditions with low cloud and heavy snowfall hampered an air search; however, aircraft wreckage and cargo [were] found on steep, mountainous snow-covered terrain by ground searchers at approximately 1645,” the report said.

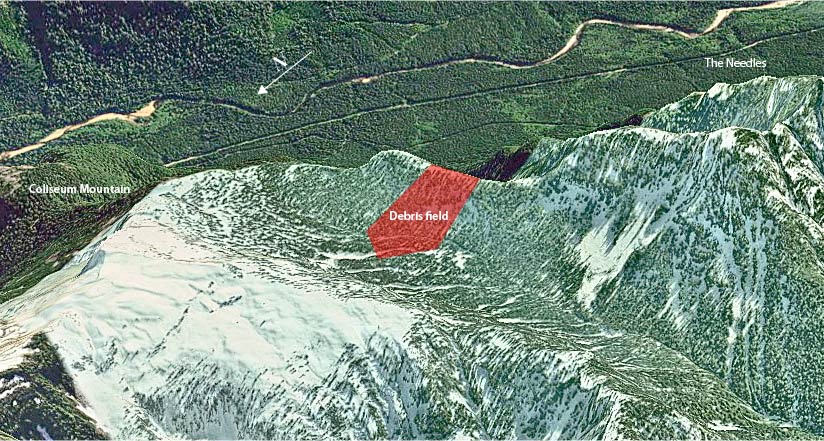

The site was about 15 nm (28 km) north of Vancouver International Airport. The debris field was 1,400 ft (427 m) long and 1,000 ft (305 m) wide, and extended from the top of a 3,400-ft ridgeline. “Lighter, less massive components were located at the beginning of the field, while heavier components were found at the furthest distances,” the report said. “The pattern was consistent with estimated ballistic trajectories of falling debris from the aircraft’s breakup point [between 5,000 ft and 3,400 ft].”

About 98 percent of the aircraft and the cargo was recovered from the accident site. “To the extent possible, given the severity of the damage, examination of the wreckage revealed no evidence of component or system failure that may have contributed to the accident,” the report said. “All components of the aircraft showed damage consistent with aerodynamic overload resulting from the high speeds reached during the rapid descent.” The examination showed, for example, that the structural overload had resulted in both wings folding upward, causing the propellers to contact the fuselage.

Full Nose-Down Trim

The Metro did not have, and was not required to have, a flight data recorder or a cockpit voice recorder. “Consequently, the investigation was unable to determine why the aircraft initially descended or why the pilots did not recover before structural failure [occurred],” the report said.

Investigators determined that the aircraft was within weight-and-balance limits and that the center-of-gravity location would have required the horizontal stabilizer to be trimmed close to its nose-down limit. “The investigation determined that, at the time of the crash, the horizontal stabilizer trim actuator was positioned to its maximum extension, resulting in a full aircraft nose-down trim setting,” the report said. “It was determined that no mechanical failure or malfunction of the actuator had occurred before the breakup.” Thus, it is possible that the stabilizer trim had been manually trimmed full nose-down.

The mountains at the accident site rise to 4,744 ft. The ceilings in the area were variable, with overcasts estimated as low as 5,000 ft. “Winds were light from the south-southeast,” the report said. “There was no precipitation. A number of aircraft transited the area of [the Metro’s] last radar position both immediately before and after the accident. Pilot reports from these aircraft described smooth flying conditions with light turbulence and cloud tops at 14,000 ft. Light rime icing conditions were reported in cloud. Satellite weather coverage showed no significant cumulus or convective cloud in the area where the accident occurred.”

‘Excessive Alcohol Consumption’

The captain’s aviation medical records showed no indication of a medical condition that might have played a role in the accident, the report said. However, toxicological tests after the accident revealed high concentrations of ethyl alcohol in his blood, urine and vitreous humor (blood alcohol contents of 0.24 percent, 0.25 percent and 0.27 percent, respectively). “These concentrations established that the captain had likely consumed alcohol over a period of several hours, until shortly before the flight’s departure,” the report said.

“BAC [blood alcohol content] calculators indicate that, to attain a BAC of 0.24 percent, an average male with a weight similar to the captain’s would have to consume approximately 17 to 20 standard drinks over a 12-hour period,” the report said. “If consumption had taken place over a 4-hour period immediately before reporting for work, a BAC of 0.24 percent would have required approximately 14 standard drinks.”

An autopsy revealed atherosclerosis (narrowing of the arteries), steatosis (a high concentration of fat in the liver) and hepatitis (inflammation of the liver). “Finding these conditions in a 34-year-old person suggests excessive alcohol consumption over a significant period,” the report said.

“Ethyl alcohol impairs human performance, having negative effects on virtually all types of cognitive functions and psychomotor abilities,” the report said. “Alcohol also affects risk-taking behaviour, in that it promotes taking actions on impulse, without a full appreciation of, or concern about, the potential negative consequences of such actions. The effects of alcohol on risk-taking behaviour are of particular concern when alcohol is used by pilots.” (Table 1 shows typical effects of alcohol use. The report noted that the effects can vary with a person’s level of tolerance of alcohol.)

| BAC (%)* | Typical Effects on Behavior and Performance |

|---|---|

|

BAC = blood alcohol content * BAC percentage is determined from grams of alcohol per deciliter of blood. Source: Federal Aviation Administration, FAA-H-8083-25A, Pilot’s Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge (2014). |

|

| 0.01–0.05 | Average individual appears normal |

| 0.03–0.12 | Mild euphoria, talkativeness, decreased inhibitions, decreased attention, impaired judgment, and increased reaction time |

| 0.09–0.25 | Emotional instability, loss of critical judgment, impairment of memory and comprehension, decreased sensory response, and mild muscular incoordination |

| 0.18–0.30 | Confusion, dizziness, exaggerated emotions (anger, fear, grief), impaired visual perception, decreased pain sensation, impaired balance, staggering gait, slurred speech, and moderate muscular incoordination |

| 0.27–0.40 | Apathy, impaired consciousness, stupor, significantly decreased response to stimulation, severe muscular incoordination, inability to stand or walk, vomiting, and incontinence of urine and feces |

| 0.35–0.50 | Unconsciousness, depressed or abolished reflexes, abnormal body temperature, and coma; possible death from respiratory paralysis (at a BAC of 0.45% or higher) |

Some of the captain’s colleagues suspected that he had a drinking problem. “On at least one occasion, a company employee told a Carson Air supervisor that he had smelled alcohol on the captain’s breath,” the report said. “However, the supervisor did not detect an alcohol odour, so the issue was not pursued further. Instead, a decision was made to monitor the situation.”

In addition, the captain occasionally was observed to be shaking while flying. This likely was a symptom of withdrawal, the report said. However, “some pilots believed that this was related to being nervous, since it seemed to be worse during training and proficiency check flights.”

‘Functional Tolerance’

The captain likely had built up a high degree of tolerance to the effects of alcohol. “Chronic heavy drinkers often display functional tolerance [emphasis added], showing few obvious signs of intoxication even at a very high BAC that, in others, would be incapacitating or even fatal (e.g., more than 0.35 percent BAC),” the report said. “For example, research on people with alcohol dependence who voluntarily entered a detoxification centre for treatment showed that many had normal speech and gait … even with BACs of 0.35 percent and greater.” Social drinkers typically show behavioral signs of intoxication at a BAC of 0.10 percent.

Heavy drinkers also can build a metabolic tolerance of alcohol. “Metabolic tolerance is an increased rate of blood alcohol clearance, or more rapid elimination of alcohol from the body, that develops over time with chronic drinking,” the report said. “It results in a lower BAC for the same amount of alcohol ingested.”

The captain’s apparent high tolerance of alcohol may explain why none of his colleagues noticed anything amiss the morning of the accident. “Those who are tolerant to the effects of alcohol show fewer signs of impairment and intoxication at a high BAC than others who are not tolerant,” the report said. “On the morning of the occurrence, the captain was observed speaking with other company pilots, using a computer, walking and loading cargo. No abnormal behaviour was observed.”

Although tolerance can mask the outward signs of intoxication, it does not provide immunity to alcoholic impairment. “Alcohol impairs almost all forms of cognitive functioning, including attention, information processing, decision making and reasoning,” the report said. “The performance of any complex or demanding cognitive task, including flying an aircraft, is consequently impaired by alcohol because of these effects.”

Although tolerance can mask the outward signs of intoxication, it does not provide immunity to alcoholic impairment. “Alcohol impairs almost all forms of cognitive functioning, including attention, information processing, decision making and reasoning,” the report said. “The performance of any complex or demanding cognitive task, including flying an aircraft, is consequently impaired by alcohol because of these effects.”

Alcohol also can adversely affect visual and vestibular functions, and thus contribute to spatial disorientation, the report said. “Alcohol-related impairment of vestibular function can decrease a pilot’s perception of aircraft attitude and impair visual tracking and visual fixation. This can lead to reduced ability to control the aircraft, see the instruments, maintain situational awareness and avoid collisions.”

Link to Suicidal Behavior

Research has shown a significant relationship between alcohol use and suicidal behavior, the report said. One sign of increased risk of suicide is social withdrawal. “The captain, who lived alone and did not routinely socialize with co-workers, mostly kept to himself,” the report said. “His co-workers and family were not aware of how he spent his time outside work. On the few occasions when the captain did join his co-workers to socialize, he was not observed drinking alcohol excessively.”

Research also has shown that widespread media coverage of events involving suicide or murder can breed similar “copycat” acts, the report said. For example, an increase in fatal airplane accidents following such events has been documented.

“On 24 March 2015, 20 days before this accident, a first officer who had been having symptoms of depression and psychosis deliberately flew a Germanwings Airbus A320 into terrain, killing all on board,” the report said.

Erroneous Airspeed Indications?

Due to the extent of damage to the aircraft and the absence of voice and flight data, investigators were unable to determine why the Metro suddenly pitched nose-down and why the pilots were unable to recover from the descent before the aircraft was torn apart by aerodynamic forces. There was no evidence that environmental conditions or a pre-existing system malfunction was involved in the accident.

Based on the findings of the investigation, the report provided three theories about what might have caused the crash: a blockage of the pitot system by ice; pilot incapacitation; and an intentional act.

“Failure or improper use of the pitot anti-icing system may have resulted in erroneous airspeed indications due to ice accumulation in the pitot tubes when the aircraft entered icing conditions in cloud,” the report said. The pitot-heat controls are located in a position that could be seen and reached only by the captain, and there is no annunciation of system status.

“Given the captain’s level of impairment and the first officer’s limited experience on the aircraft, the pitot heating system may not have been in operation at the time,” the report said. “If a pitot system blockage resulting from ice occurred while in cloud, the pilots may have inadvertently initiated a descent while attempting to ascertain what was happening with the aircraft.”

However, the rapid descent would have produced vertical accelerations and negative g forces that would have been readily apparent to the pilots. “Further, the high rate of descent and airspeed during the dive continued for a period exceeding 10 seconds, which would likely have provided the pilots with sufficient time to recognize the flight path deviation and/or aircraft system malfunction and initiate some type of recovery action before impact,” the report said.

Pilot Incapacitation?

However, incapacitation might have rendered the pilots unable to recognize the situation and recover control of the aircraft. Investigators found no evidence of an event that might have incapacitated both pilots. Furthermore, “there was no indication, or reason to suggest, that the first officer became incapacitated in the moments leading up to the descent,” the report said.

The captain’s heavy drinking before the flight could have led to incapacitation. “Alcohol intoxication almost certainly played a role in the events leading to the accident,” the report said. “The captain’s tolerance to some of the effects of alcohol likely allowed his impairment to go undetected on the morning of the accident. However, a BAC of 0.24 percent would have resulted in significant impairment in the captain’s cognitive and psychomotor performance during the flight.”

Such impairment likely would have caused spatial disorientation, making it difficult for the captain to interpret information from the flight instruments, including the airspeed indicator, and to maintain control of the aircraft.

Lacking recorded flight and voice data, investigators were unable to determine if the first officer had interceded. “If the captain had become completely incapacitated, the first officer should have been able to take control of the aircraft if physically able to do so,” said the report.

Intentional Act?

Although there was no clear evidence that the captain was predisposed to commit an intentional act, several factors are consistent with the theory that the captain intentionally placed the Metro into the fatal descent. “These factors include the absence of technical or environmental factors to explain the sudden, rapid descent; the aircraft’s full nose-down trim setting; the aircraft’s descent in the direction of flight; the absence of any type of emergency communications (e.g., Mayday call) from the pilots to air traffic control; and the absence of any apparent recovery action during the descent,” the report said.

The intentional-act theory is supported by the autopsy results showing signs of long-term, untreated alcohol abuse and dependence — conditions that are associated with increased risk of suicide. “Suicide accounts for 20 percent to 33 percent of the increased death rate among those with alcohol dependence compared to the general population,” the report noted.

Because of the absence of information about what occurred in the Metro cockpit before the fatal descent began, however, several questions about the crash— including whether or not it was a copycat act — remain unanswered.

Alcohol Testing Recommended

Based on the factual evidence uncovered during the investigation, the report concluded that “for unknown reasons, the aircraft descended in the direction of flight at high speed until it exceeded its structural limits, leading to an in-flight breakup” and that “based on the captain’s blood alcohol content, alcohol intoxication almost certainly played a role in the events leading up to the accident.”

Based on the factual evidence uncovered during the investigation, the report concluded that “for unknown reasons, the aircraft descended in the direction of flight at high speed until it exceeded its structural limits, leading to an in-flight breakup” and that “based on the captain’s blood alcohol content, alcohol intoxication almost certainly played a role in the events leading up to the accident.”

The findings of the investigation of the Metro accident prompted the TSB to recommended that the Canadian Department of Transportation “develop and implement requirements for a comprehensive substance abuse program, including drug and alcohol testing, to reduce the risk of impairment of persons while engaged in safety-sensitive functions.”

This article is based on Transportation Safety Board of Canada Aviation Investigation Report A15P0081,“In-flight Breakup: Carson Air Ltd.; Swearingen SA226-TC Metro II, C-GSKC; North Vancouver, British Columbia; 13 April 2015.”

Note

- French Bureau d’Enquêtes et d’Analyses Final Report: Accident on 24 March 2015 at Prads-Haute-Bleone (Alpes-de-Haute-Provences, France) to the Airbus A320-21, Registered D-AIPX, Operated by Germanwings.

Further Reading

Werfelman, Linda. “Intentional Acts.” Flight Safety Foundation AeroSafety World. May 2016.

Image credits

Featured image: composite, Susan Reed; man in a bottle, © MaryValery | VectorStock; North Shore Mountains, © Edgar Bullon | Dreamstime

Aircraft wreckage © Transportation Safety Board of Canada

Swearingen Metro II: © One Mile Up Federal Clip Art

Debris field: composite, Susan Reed; background, © Google Earth; debris field extent, Transportation Safety Board of Canada

Man in a bottle icon: © David Yu | The Noun Project CC-BY 3.0

Sobriety test icon: © Luis Prado | The Noun Project CC-BY 3.0