The loss of Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 was a “one in 100 million flight event,” the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) said in a statement marking the first anniversary of the March 8, 2014, disappearance of the Boeing 777-200ER.

Even as the search for the missing airliner continues, the aviation industry has moved to address gaps in its safety procedures intended to reduce the likelihood of similar events in the future by improving the ability of searchers to locate aircraft that crash in remote areas, ICAO said.

“The aviation sector has … learned from MH370 that we must respond to even very rare events in our network when there is a question of public trust involved,” ICAO said, adding that the response to this event has been cooperative and “as a matter of high priority.”

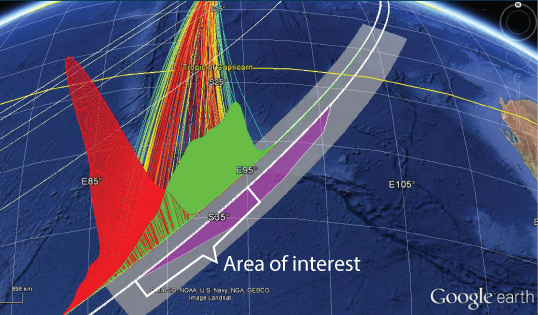

The airplane and its 239 occupants disappeared during a scheduled flight from Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, to Beijing. Air traffic control lost contact with the 777 about 40 minutes after takeoff, when it transitioned from Malaysian to Vietnamese airspace. Subsequent analyses of radar data and satellite communication system signaling messages indicated that the airplane had flown — off course — across the southern Indian Ocean. It is presumed to have crashed, after its fuel supply was exhausted, into the ocean in an area that is part of Australia’s search-and-rescue zone.

The Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB), which is leading the search, has used the analyses to try to pinpoint the likely location of the airplane. The analyses are being conducted by a team of scientists from Australia, Malaysia, the United Kingdom and the United States.

“Refinements to the analysis of both the satellite and flight data have been continuing,” the ATSB said in an October report on its progress. “This ongoing work may result in changes to the prioritisation and locale of search activity over the period of the underwater search.”

A subsequent ATSB report, issued in December, explained how an international team of specialists has used burst timing offset — a measurement of the time required for a signal to travel from a ground station to a satellite to an aircraft and back to the ground station — to calculate the area where the 777 most likely entered the water.

Months of searching by 82 aircraft and 84 vessels from 26 countries have found no sign of the airplane, but as the first anniversary of the disappearance approached, Malaysian Transport Minister Liow Tiong Lai said in a television interview1 that he fully expected the airplane’s wreckage to be discovered within several months, as experts complete their search of a 60,000-sq-km (23,166-sq-mi) area southwest of Australia.

Data “all point out that the plane ended up in the south Indian Ocean,” he said.

On the first anniversary of the disappearance, his office issued a 585-page interim factual report detailing information gathered during the first year of the accident investigation.2

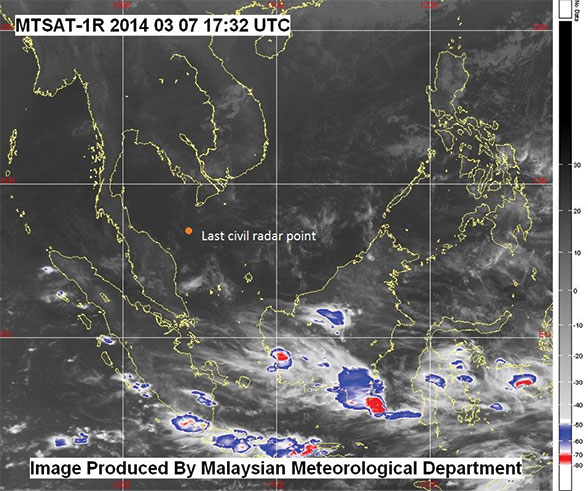

In addition to describing the search for the airplane, the report discusses personnel information, noting that there were no unusual financial, health or behavioral issues affecting the flight crew; airplane information, noting that an examination of records revealed no significant defects and showed that the airplane and its engines were in compliance with all airworthiness directives; airline information, which included descriptions of the organization’s multiple safety programs; a list of cargo, which included 2,453 kg (5,408 lb) of lithium-ion batteries and walkie-talkie accessories and chargers, along with books, electrical equipment, documents and fresh mangosteens; weather information, which indicated that no significant adverse weather conditions had been expected along the planned route; and air traffic control information, including dozens of pages of transcripts that reported communications among controllers trying to determine exactly when contact was lost with the airplane.

ELT Issues

Although the airplane was equipped with four emergency locator transmitters (ELTs) — one fixed ELT, one portable ELT and two ELTs packed within slide raft assemblies — the report noted that ELTs are intended for use at or near the water’s surface; their signals cannot be detected when an ELT is submerged in deep water. If an ELT, its wiring or its antenna is damaged, it may not transmit effectively — or at all. Similar problems arise if an ELT is shielded by wreckage or terrain.

The report added that a review of ICAO accident records for the past 30 years showed that, of 257 accident aircraft, 173 were equipped with ELTs. Of those 173 aircraft, ELTs activated correctly in 39.

“The detection of ELT signals after an aircraft crash remains problematic,” the report said. “Several reports have identified malfunctions of the beacon-triggering system, disconnection of the beacon from its antenna or destruction of the beacon as a result of accidents where aircraft [were] destroyed or substantially damaged.”

In addition, the Cospas-Sarsat Programme, the international system that coordinates the detection of distress signals, “does not provide a complete coverage of the Earth at all times,” the report said. “As a consequence, beacons located outside the areas covered by these satellites at a given moment cannot be immediately detected, and must continue to transmit until a satellite passes overhead.”

Also, Cospas-Sarsat satellites currently detect only signals from 406 MHz ELTs, not the older 121.5/243 MHz beacons. The fixed and portable devices in the MH370 aircraft were 406 MHz, but the slide/raft ELTs were 121.5/243 MHz beacons.

Flight Recorders

The airplane was equipped with a solid-state flight data recorder (FDR) and solid-state cockpit voice recorder, both of which had the required underwater locator beacon (ULB) designed to transmit for at least 30 days at ocean depths of as much as 20,000 ft. The battery in the FDR’s ULB apparently expired in December 2012, according to maintenance records, and might have stopped functioning, the report said, adding that maintenance personnel said that the computer system that tracked such maintenance issues was not correctly updated when the FDR was replaced in 2008. The problem was recognized only after the disappearance of MH370, when accident investigators requested detailed information about the ULBs, the report said.

“There is some extra margin in the design to account for battery life variability and ensure that the unit will meet the minimum requirement,” the report said. “However, once beyond the expiry date, the ULB effectiveness decreases so it may operate for a reduced time period until it finally discharges. While there is a definite possibility that a ULB will operate past the expiry date on the device, it is not guaranteed that it will work or that it would meet the 30-day minimum requirement.”

Recommendations

The investigation has been the impetus for a number of safety recommendations and renewed calls for alternative methods of locating aircraft wreckage after accidents in remote areas, and recovering flight data. The recommendations call for improved aircraft position reporting, deployable flight recorders, triggered transmission of critical flight data and longer-lived ULBs (ASW, 3/15).

Most recently, ICAO’s High Level Safety Conference agreed in February to recommend the adoption of its Global Aeronautical Distress and Safety System, which includes a 15-minute tracking standard for normal flight operations — considered a step toward global flight tracking — and a one-minute tracking requirement for aircraft in abnormal or distress situations. The next step would be formal adoption of the measure by the ICAO Council, which is considered likely later this year.

ICAO characterized the 15-minute requirement as “performance-based and not prescriptive, meaning that global airlines would be able to meet it using the available and planned technologies and procedures they deem suitable.”

Plans call for coordinated regional exercises after the standard is adopted, ICAO said, noting that the exercises would be designed to aid countries with “both the standard’s introduction and their ability to respond to abnormal flight behaviour scenarios in an integrated manner.”

Notes

- CNN. Television interview with Liow Tiong Lai. March 6, 2015.

- Malaysian Ministry of Transport. Factual Information: Safety Information for MH370. March 8, 2015.

Featured image: Harris Shiffman | Dreamstime.com

Search area: Australian Transport Safety Bureau

Meteorological radar image: Malaysian Meteorological Department