With a steady increase in reports of disruptive passengers interfering with commercial flights, the industry and its regulators have launched multiple campaigns to crack down on unruly behavior.

Although the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) cautions that comprehensive data are not available because of the absence of a uniform reporting system, the International Air Transport Association (IATA) says that it received more than 66,000 reports of unruly passengers between 2007 and 2017. In 2017 alone, IATA said, 8,731 incidents were reported — the equivalent of one incident in every 1,053 flight sectors, or a rate of 0.95 incidents per 1,000 flight sectors, up from 0.73 incidents per 1,000 sectors the previous year (“Getting Out,” ASW 4/19).1

In reality, the number of incidents probably is higher, IATA said, noting that airlines sometimes do not turn over these data to IATA, either because a separate security department handles the incidents or because airline records do not include all incidents.

ICAO said that incidents of unruly and disruptive behavior include assault, fights among passengers, child molestation, sexual harassment and assault, disorderly conduct as a result of alcohol intoxication, illegal consumption of drugs, refusal to follow a crewmember’s lawful instruction, vandalizing the cabin interior, and the unauthorized use of personal electronic devices.

“It has been noted that ‘what happens generally in the street is now happening on board aircraft,’” ICAO said in its Manual on the Legal Aspects of Unruly and Disruptive Passengers. 2 “In a number of cases, the acts and offences directly threatened the safety of the aircraft. In some cases, the aircraft commander had to make an unscheduled stopover to disembark the unruly and disruptive passenger for safety reasons. These are the occurrences which particularly cause international concern.”

IATA said that the incidents have a “disproportionate impact” on flight operations, “threatening safety, disrupting other passengers and crew, and causing delays and diversions. However, due to loopholes in existing laws, such offenses often remain unpunished.”

Although most reported incidents are classified as “minor” or “moderate,” IATA has expressed concern about the increase in recent years in the number of incidents that are considered “serious” or “flight deck security” events. In 2017, of the 8,731 reported incidents, 84 percent were classed as “minor” and 9 percent as “moderate.” Of the more serious incidents, 3 percent were considered “serious” in that they “could be interpreted as a direct threat to the safety of a person or the aircraft,” and 1 percent were “flight deck security” incidents in which passengers tried to enter the flight deck or “behaved in a manner in which the security of the flight was deemed to be compromised,” IATA said.

IATA worked with ICAO to develop ICAO’s new legal guidance on the most appropriate methods of managing disruptive and unruly passengers. That guidance is included in ICAO’s manual, officially released in June with a joint announcement by ICAO Secretary General Fang Liu and IATA Director General and CEO Alexandre de Juniac. The document includes model legislation for handling a number of unruly and disruptive incidents aboard aircraft, as well as guidance material for establishing a program of administrative sanctions against those who commit these incidents.

“Unruly and disruptive passenger conduct can pose distinct threats to the safety and security of aircraft, flight crew and passengers,” Liu said. “It can also generate costly disruptions to airlines and passengers alike in situations when aircraft must be diverted to manage these incidents.”

De Juniac added that the new guidance would help nations develop a harmonized approach to problems associated with unruly passengers while adhering to their own national laws. The manual “covers many practical measures for consideration by policymakers, including ‘on the spot’ fines to boost enforcement action,” he said.

The manual emphasizes that crewmembers require special protection, “since harming them physically or intimidating them or [making] threats against them would have consequences on their ability to carry out their safety and security responsibilities.”

Legal Jurisdiction

The Montreal Protocol, a 2014 ICAO initiative not yet fully ratified by ICAO member nations, is designed to ensure that authorities in the country where an aircraft lands have jurisdiction over disruptive actions that have taken place during flight. In most cases, existing law assigns jurisdiction to the country where the aircraft is registered, and as a result, when unruly passengers are turned over to local authorities after landing, they often are released without charges.

Ratification of the document, ICAO said, would “strengthen the capacity of states to curb the escalation of the severity and frequency of unruly behavior on board aircraft. The Protocol also recognizes the desire of many states to assist each other in curbing unruly behavior and restoring good order and discipline on board aircraft.”

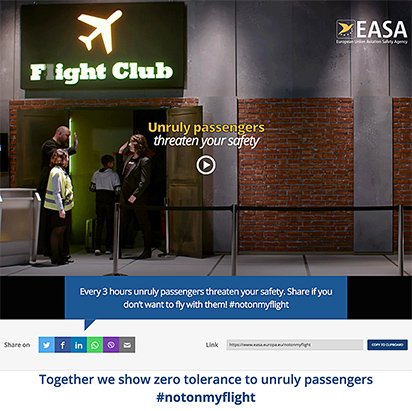

‘Not on My Flight’

IATA has joined in a number of regional efforts to combat unruly behavior, including the European Union Aviation Safety Agency’s (EASA’s) “Not on My Flight” initiative, an informational campaign to increase awareness of unruly behavior and its consequences.3

“Any kind of unruly or disruptive behaviour, whether related to intoxication, aggression or other factors, introduces an unnecessary risk to the normal operation of a flight,” EASA said in its announcement of the campaign in April.

The agency cited data that show that, on average, one incident of unruly or disruptive behavior occurs every three hours on a flight within the European Union, with at least 70 percent of these incidents involving aggressive actions. At least once a month, an incident escalates and the flight crew conducts an emergency landing to deal with the problem.

“These figures are worrying as they demonstrate an increasing trend,” EASA says. “What is particularly disturbing is that these incidents have a direct impact on both the safety of crew and passengers.”

‘One Too Many’

A similar public information campaign by U.K. airlines, airports, airport police and elements of the travel industry was implemented in mid-2018, urging passengers to “fly responsibly or you could pay the price.”

The “One Too Many” campaign — aimed specifically at unruly behavior fueled by alcohol consumption — tells potential passengers that “one too many is all it takes to ruin a holiday, cause a delay, cancel a flight, land you in jail, divert a plane.” If unruly passenger behavior leads to cancellation of a flight, the passenger could be banned from future flights, the campaign says.

Participating organizations also developed an aviation industry “Code of Practice on Disruptive Passengers,” which warns of the significant impact of disruptive behavior for other passengers, crewmembers and airport employees as well as for the disruptive passengers themselves.

“The results can be a nuisance and annoyance at one end of the scale, to threats to passengers, crew and aircraft safety at the other,” the organizations said.

During a 2015 meeting, the organizations — after agreeing that more consistency was needed in addressing the problem — developed a voluntary code aimed at minimizing the number of disruptive passenger incidents.

The code specifies that its official supporters “take a zero-tolerance approach to disruptive behaviour” and will try to preempt such behavior in order to avoid potential incidents, that they will train their staff in managing passengers with disruptive behavior, that they will “practice the responsible and controlled selling or supplying of alcohol” and that they will promote “responsible and considerate behaviour among air passengers.”

Among the specific points: that police should investigate all reported incidents and take appropriate action, including seeking prosecution; that employees will have the necessary procedures, guidance tools and training to manage disruptive behavior by passengers; that airlines, bars, restaurants and retailers will not supply alcohol to a person whom they believe is intoxicated; and that participating organizations will educate passengers about why disruptive behavior is a problem.

FAA Reports

In the United States, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) received reports of 90 incidents in 2017 involving disruptive passengers, down from 101 reports in 2016 and well below a peak of 310 reports in 2004. The numbers are presumably smaller than the actual number because security violations — which are handled by the Transportation Security Administration — are not included and because reporting is at the discretion of the crewmembers who were involved in or witnesses to the incidents.5

Under a 2000 law, the FAA may propose a civil penalty of as much as $25,000 for disruptive passengers who interfere with a crewmember’s duties, or the passengers may be prosecuted on criminal charges.

The US. National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s Aviation Safety Reporting System (ASRS), in a sampling of recent reports, cited a series of examples of unruly passenger behavior.6

Among them was a March 2018 incident reported by the captain of a passenger airliner, who said that the purser informed him of a passenger who was “caught vaping, smoking, had cigarette lighter, [was] drunk and [was] harassing other passengers. Purser advised that [the passenger] had become physically and verbally abusive, shoving flight attendants.”

The incident was classified as Level 2, meaning that it involved physically abusive behavior. Later in the flight, the passenger became ill and crewmembers discovered that he had an empty bottle of sleep-inducing medicine. Police and medical personnel met the airplane when it landed, and the passenger deplaned “on his own, after being admonished,” the ASRS report said.

In another ASRS submission, a flight attendant on a passenger airliner reported seeing a passenger repeatedly punch another flight attendant, “causing injury and blood.”

The passenger “was hurling insults at the flight attendant and the airline, while demanding … ice, just before beginning to punch [the flight attendant] numerous times,” the report said. “Passenger went to the restroom … only after screaming that he would cause more harm (to the flight attendant) if he walks by again. … (Passenger) began destroying the aircraft bathroom and causing immense injury to himself … . (Passenger’s) wife said that they had been stuck in (another city) for numerous days and he was upset with (the airline).”

Notes

- IATA. IATA Safety Report 2018, Edition 55, Section 7, “Cabin Safety.” April 2019.

- ICAO. Doc 10117, Manual on the Legal Aspects of Unruly and Disruptive Passengers.

- EASA. “‘Not on My Flight’ Campaign Draws Attention to Safety Impact of Unruly Behaviour on Flights.” April 3, 2019.

- Airlines UK, Airport Operators Association, UKHospitality, UK Airport Police Commanders, UK Travel Retail Forum. “The UK Aviation Industry Code of Practice on Disruptive Passengers.”

- FAA. “Passengers and Cargo: Unruly Passengers.” Updated Feb. 4, 2019.

- ASRS. Database Report Set: Passenger Misconduct Reports. Aug. 31, 2018.

Featured image: composite, Susan Reed; background, © enviromantic | iStockphoto; enraged man, © blamb | iStockphoto

Fighting passengers: composite, Susan Reed; airplane seat, © Aimagenarium | VectorStock; fighting men, © Zhitkov | VectorStock