On the evening of Jan. 8, 2014, a U.S. Air Force (USAF) Sikorsky HH-60G Pave Hawk helicopter took off from RAF Lakenheath in the United Kingdom. The U.S. crew of four was practicing a nighttime rescue mission and was flying the aircraft about 110 ft above ground level (AGL) at 110 kt when they inadvertently passed over Cley Marshes, a nature reserve well known for its resident bird populations. Apparently startled by the noise of the aircraft, a flock of geese took off into the path of the helicopter. Several birds crashed through the windscreen, hitting the pilot and copilot and rendering them unconscious. At least one other bird hit the nose of the aircraft, disabling the trim and flight stabilization systems. The helicopter crashed to the ground in seconds, killing the pilots and two other crewmembers. The aircraft was destroyed.

Bird strikes have been a serious problem since the beginning of powered flight, according to a number of historical information resources. The first bird strike ever recorded was noted by Orville Wright in his diary in 1905, after his Wright Flyer struck a bird while flying over a cornfield in Ohio. Apparently, there was no damage to the airplane. The first recorded bird strike fatality occurred April 3, 1912, when an airplane flown by aviation pioneer Cal Rodgers — who in 1911 had become the first person to fly across the United States — collided with a seagull during a demonstration flight near Long Beach, California, U.S. Rodgers was killed after he lost control of the airplane, and it crashed into the Pacific Ocean.

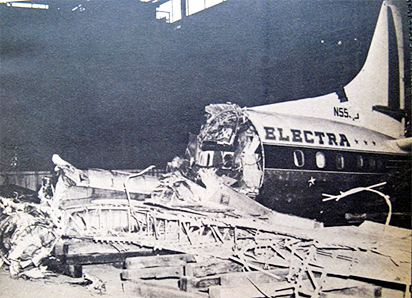

The worst bird strike accident in terms of loss of life occurred on Oct. 4, 1960. Eastern Air Lines Flight 375, a Lockheed L-188 Electra, had just taken off from Logan Airport in Boston when it flew into a flock of starlings at an altitude of 120 ft. Three of the airplane’s four turboprop engines ingested one or more birds, drastically reducing power and resulting in the shutdown of one engine. The loss of thrust and airspeed, and the asymmetry of the thrust, caused the pilots to lose control of the airplane, which crashed into Boston Harbor, killing 62 people.

But the most famous recent bird strike accident had a “happy ending” for the airplane occupants. US Airways Flight 1549, an Airbus A320-200 with 155 people on board, struck a flock of Canada geese shortly after takeoff from New York LaGuardia Airport on Jan. 15, 2009. Enough of the birds were ingested to cause loss of thrust in both engines. Chesley Sullenberger, the captain, and Jeffrey Skiles, the first officer, safely ditched the gliding airplane in the Hudson River in what was called the “miracle on the Hudson.”

The military also has had its share of bird strikes. The worst such U.S. military accident occurred Sept. 22, 1995, when a USAF Boeing E-3 Sentry airborne warning and control system (AWACS) aircraft, taking off from Elmendorf Air Force Base in Anchorage, Alaska, encountered a flock of Canada geese. Both port side engines lost power due to ingested material. The airplane crashed 2 nm (4 km) from the runway, killing all 24 on board and destroying the airplane.

Birds aren’t the only concern. While taking off or landing, pilots occasionally have to contend with terrestrial animals that have wandered onto the runway. On Nov. 17, 2012, a Cessna Citation II being used by U.S. Customs and Border

Protection was on a landing rollout at the Greenwood (South Carolina) County Airport. A deer ran out from the woods and struck the airplane on the left side above the left landing gear, rupturing a fuel cell. The spilling fuel caught fire. The pilot stopped the airplane, and the crew safely evacuated. However, the ensuing fire destroyed the airplane.

To better understand the magnitude of the wildlife strike problem in the United States, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) in 1990 began requesting that pilots and airport personnel report all strikes, regardless of damage. Today, reports can be filed electronically using a website <wildlife.faa.gov/strikenew.aspx> or on paper. To try to determine what types of wildlife are being encountered, the official “Wildlife Strike Report” requests that reporters identify the particular species involved in the strike. If identification of a struck bird/other animal is impossible but the remains are available, they can be sent to the Smithsonian Institution’s Feather Identification Lab, where experts can determine the species of bird involved. Other countries have similar programs.

In 1995, the FAA, in conjunction with Department of Agriculture Wildlife Services, started work on a wildlife strike database. The FAA serial report “Wildlife Strikes to Civil Aircraft in the United States” first was published in 1996 and is issued every year. The latest report was released in August 2015 and covers the period from 1990 through 2014..

In 1995, the FAA, in conjunction with Department of Agriculture Wildlife Services, started work on a wildlife strike database. The FAA serial report “Wildlife Strikes to Civil Aircraft in the United States” first was published in 1996 and is issued every year. The latest report was released in August 2015 and covers the period from 1990 through 2014..

Its statistics provide a clearer picture of the wildlife problem for aviation in the United States. The number of reported strikes increased from 1,851 in 1990 to a record 13,668 in 2014, partially because pilots have become more receptive to the reporting procedure. However, it should be noted that bird populations — especially those of larger birds — have increased in recent years, as has air traffic. Also, it is believed that because newer turbofan-powered aircraft are quieter than transport jets of earlier years, they are less recognizable to birds. Keep in mind that the data represent only strikes that were officially recorded and underestimate the actual numbers (ASW, 6/15).

Most wildlife strikes cause no damage. In 2014, 581 strikes, or 4 percent of all reported strikes, resulted in damage to the aircraft. And the number of damaging strikes actually has decreased 24 percent since 2000, likely due to wildlife strike–prevention efforts. The decrease occurred for commercial air transport aircraft, not general aviation (GA) aircraft, where the damaging strike rate has remained fairly constant. However, this still leaves a significant problem. Between 1990 and 2014, 67 aircraft of all categories were destroyed or damaged beyond repair by wildlife strikes. More than 60 percent of these were smaller GA aircraft.

Noting that a precise estimate of monetary losses is difficult, the latest report estimated that in 2014, wildlife strikes resulted in 172,151 hours of down time and $208 million in direct and indirect costs. But the report also said that “actual costs are likely two or more times higher than these minimum estimates.” Over the 25-year period covered by the data, 12 fatal wildlife strike incidents resulted in the deaths of 26 people. In terms of the U.S. military experience, the Air Force reported over 69,000 strikes since 1995, 23 fatalities, 12 aircraft destroyed and over $400 million in damage. Around the world since 1988, bird/other wildlife strikes have resulted in 258 deaths and 245 aircraft destroyed. The European Space Agency has estimated that bird/other wildlife strikes around the world cost airlines over $1 billion a year.

Noting that a precise estimate of monetary losses is difficult, the latest report estimated that in 2014, wildlife strikes resulted in 172,151 hours of down time and $208 million in direct and indirect costs. But the report also said that “actual costs are likely two or more times higher than these minimum estimates.” Over the 25-year period covered by the data, 12 fatal wildlife strike incidents resulted in the deaths of 26 people. In terms of the U.S. military experience, the Air Force reported over 69,000 strikes since 1995, 23 fatalities, 12 aircraft destroyed and over $400 million in damage. Around the world since 1988, bird/other wildlife strikes have resulted in 258 deaths and 245 aircraft destroyed. The European Space Agency has estimated that bird/other wildlife strikes around the world cost airlines over $1 billion a year.

According to the FAA report, “The aircraft components most commonly reported as struck by birds from 1990–2014 were the nose/radome, windshield, wing/rotor, engine and fuselage.” Of strikes inflicting damage, the engines were affected most often and, as illustrated by the incidents previously described, represent the greatest risk for major accidents. As for terrestrial animals, the report says that “most commonly reported as damaged were the landing gear, wing/rotor, propeller and “other.” Terrestrial animals pose the greatest risk at smaller, GA airports where perimeter fencing is absent.

Approximately 6 percent of bird strikes caused a negative effect on flight, and that percentage grew to 21 percent for terrestrial animal strikes, the report said. This includes precautionary or emergency landings and rejected takeoffs. For the landing incidents, 48 of 5,217 events included jettisoning of fuel, an average of 14,136 gal (53,510 L) per incident.

Most bird strikes occur at lower altitudes. Over 70 percent of strikes occurred at or below 500 ft AGL. For commercial aircraft, the greatest threat occurs at and near airports when aircraft are taking off or are in the landing phase, including approach. For GA, any low-level flight carries a strike risk. Bird strikes decreased markedly with increases in altitude (about 34 percent for every 1,000 ft gain in altitude). However, there is no perfectly safe altitude or flight level. The U.S. record for the highest bird strike on a commercial aircraft is 31,300 feet AGL. The world record for the highest bird strike — 37,000 ft — was set Nov. 29, 1973, on a commercial flight over Abidjan, Ivory Coast. And although the number of damaging strikes has decreased below 1,500 ft AGL (likely due to preventative measures), the number of damaging strikes above this altitude has stayed the same.

The FAA report noted that 518 species of birds have been struck since 1990. Of these, 214 species have caused damage. Doves/pigeons represent the most commonly struck birds (specifically, mourning doves lead the strike list). Larger bird species, especially waterfowl, gulls and raptors, are associated with the most damaging strikes. Waterfowl strikes comprised 29 percent of all damaging strikes. The Canada goose produced the most damaging strikes — 757 over the 25-year period. Not only are these bird larger than most, they also tend to fly in flocks.

Flocks of birds pose a greater risk because they increase the probability of a strike. Also, in terms of engine-ingestion effects, there is more biomass to potentially deal with. Even small birds, if there are enough of them, can cause engine problems and engine failure. Even one bird can bring disaster. On Sept. 28, 2012, a Sita Air Dornier 228-200 operating as Flight 601 crashed just after takeoff from Tribhuvan International Airport in Nepal, killing all 19 people on board. The airplane had struck a black kite, a raptor common in the region.

The FAA study showed that over half of bird strikes in the United States occurred in the four-month period from July through October, the end of nesting and beginning of fall migration. Nearly two-thirds of the bird strikes occurred during the day, when birds are most active. As to flight phases, landing is nearly twice as hazardous as takeoff.

From 1990–2014, 3.1 percent of all reported wildlife strikes involved animals other than birds. Strikes of bats accounted for 0.9 percent of all reported strikes, but these small flying mammals do little damage. Of the 3,360 reported strikes of terrestrial animals, 1,055, or 31 percent, damaged the aircraft, with 12 percent causing damage classified as “substantial” or greater and 30 aircraft listed as destroyed. Of the animals hit, there were 41 species of terrestrial mammals, 21 species of bats and 17 species of reptiles. In Alaska, aircraft have hit moose and caribou. Alligators and snapping turtles have been encountered on some Florida runways. Pronghorn antelope have been hit in Arizona. Planes have struck Texas armadillos. Terrestrial mammals are more likely to be encountered at night, in the fall, and during the approach and landing phases of flight.

Deer (predominantly white-tail deer) are the most common problem, accounting for one-third of all terrestrial animal strikes. Estimates of the deer population in the United States range from 15 million to 30 million. With an animal the size of a deer, contact almost always produces damage. In fact, of the 1,094 strikes involving deer from 1990–2014, 922 strikes, or 84 percent, caused damage (87 percent of all damaging terrestrial animal strikes) with a cost of $45.5 million. Twenty-four aircraft were destroyed, and there was one fatality.

Another animal that has adapted to human habitation is the coyote. Despite a never-ending attempt to limit the harm this species poses, the coyote has flourished and is found in every state except Hawaii. In the past 25 years, there have been 469 strikes involving coyotes, including 42 with damage totaling $3.8 million.

Even something as innocuous as a rabbit can cause problems. Eastern cottontails were struck 73 times over the past 25 years. Four incidents had an effect on flight, and three resulted in damage to aircraft totaling $96,000.

Domestic animals also have been struck by aircraft. The first recorded terrestrial wildlife strike involved a dog on July 25, 1909. Before Louis Blériot became the first person to fly a plane across the English Channel, a farm dog ran into the propeller blades of his Blériot XI aircraft while the engine was warming up.

Although nonfatal strikes don’t garner headlines, U.S. wildlife strikes that have a negative effect on flight — or actually do damage — occur every day.

Edward Brotak, Ph.D., retired in 2007 after 25 years as a professor and program director in the Department of Atmospheric Sciences at the University of North Carolina, Asheville.

Featured image: © north | Vectorstock

Electra: U.S. Civil Aeronautics Board

Boeing E-3: U.S. Air Force

Cessna Citation II: U.S. National Transportation Safety Board

Report cover: U.S. Federal Aviation Administration

Damaged windscreen: Henrique Rubens Balta de Oliveira — própria | Wikimedia PD

Damaged engine: © I, Plenumchamber | Wikimedia CC-BY-SA 3.0