British Airways (BA) has taken steps to mitigate human factors–related risk in its line maintenance operations by applying lessons learned during the investigation of a 2013 accident involving one of its Airbus A319s.

The airplane departed London Heathrow Airport (LHR) on May 24, 2013, with both sets of fan cowling doors on its two International Aero Engines V2500 engines unlatched, the U.K. Air Accidents Investigation Branch (AAIB) said in its final report on the accident.1 The doors detached during takeoff, and the flight crew returned to LHR, shutting down the right engine to extinguish a fire fed by leaking fuel along the way. The aircraft arrived safely, with all 75 passengers and five crewmembers evacuating the aircraft after it came to a stop on the runway.

AAIB’s probe pinpointed two primary causal factors in the accident: Two technicians who serviced the airplane “did not comply with the applicable AMM [aircraft maintenance manual] procedures,” and pre-flight walk-around inspections by a tug driver and the flight’s first officer “did not identify that fan cowl doors on both engines were unlatched.”

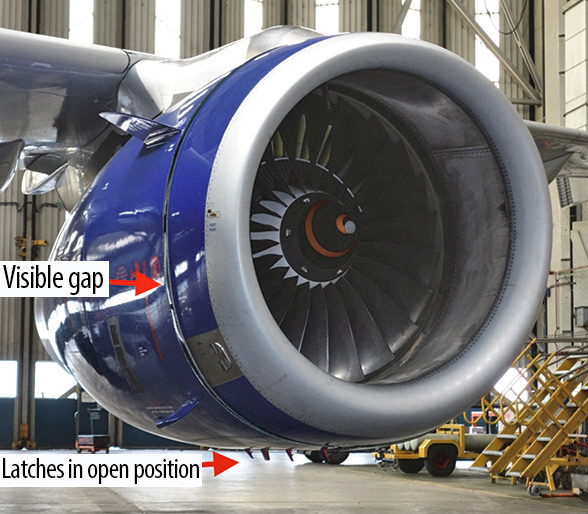

The report also noted three contributing factors: the fan cowling door latch design; the position in which the technicians left the latches — a configuration that was intended to make follow-up maintenance easier but that made the unlatched condition harder to notice; and faded paint on the airplane’s latches that also made their position harder to detect.

The report also noted three contributing factors: the fan cowling door latch design; the position in which the technicians left the latches — a configuration that was intended to make follow-up maintenance easier but that made the unlatched condition harder to notice; and faded paint on the airplane’s latches that also made their position harder to detect.

AAIB made five recommendations that addressed the latch’s design and certification standards, BA’s crew training on in-flight damage assessments, the carrier’s evacuation procedures and industrywide maintenance technician fatigue risk management systems.

Also, two general issues combined to create a series of maintenance human factors issues that laid the groundwork for the occurrence. One, which AAIB concluded was significant enough to be cited as a contributing factor, was the A320-family fan cowling door latch design. As a result of the probe and related incident analysis, Airbus is working on retrofits and forward-fit modifications on the system (see “A320 Fan Cowling Latch“).

The other factor was BA’s overnight line maintenance protocol. AAIB neither identified BA’s organizational procedures as a contributing factor to the accident nor addressed any of its five recommendations to the carrier’s maintenance and engineering division. But the investigation helped BA identify several areas that it determined needed to be strengthened based on AAIB’s probe, and the airline has made changes, according to the AAIB’s report.

First Flight

The fan cowling door loss occurred on the airplane’s first scheduled departure on the day of the accident. The work that led to the fan cowling doors being left unlatched was part of a scheduled overnight maintenance check package.

The aircraft was one of six assigned to two BA maintenance employees—identified as Technicians A and B in AAIB’s report — working their shifts as limited maintenance authority (LMA) technicians. Also assigned to the aircraft were B1 licensed aircraft engineers (LAEs), responsible for “scheduled and defect-driven mechanical maintenance outside the scope of LMA work,” and B2 LAEs, responsible for avionics systems work certification. LAEs only worked on aircraft when needed, and “no one individual had effective oversight of the work undertaken on the aircraft as a whole,” the AAIB report said.

The overnight shift in question was from 1845 local time on May 23 to 0645 on May 24. The pair was assigned work on six aircraft: two A319s, two A320s, an A321 and a Boeing 767. Each required daily maintenance checks, and two of them — the accident airplane and an A321 — also required weekly checks. Both technicians later told AAIB that the workload was not “unusual or excessive,” and both considered it achievable.

Each of the six aircraft was parked within LHR’s Terminal 5 complex. Four of them were at the main Terminal 5 building, one was at Terminal 5B, and one was at Terminal 5C. (One of the aircraft that the technicians worked on, an A320, was a late addition to their list when an aircraft originally assigned to them ended up not coming to LHR.) The two airplanes undergoing weekly checks were parked on the east side of the main Terminal 5 building, at stands 513 and 517, respectively.

Aircraft assignments did not come with ancillary information, such as “the number and scope of any recently incurred defects,” AAIB found. “This encouraged technicians to prioritize those aircraft scheduled for weekly checks (or larger aircraft, such as 767s and A321s) early in their shift, to assess the magnitude of any additional work required that might impact the progress of their other tasks during the shift.”

Technicians A and B began their work traveling in a single operations vehicle, and opted to start at Terminal 5B, with a daily check on the 767. They then moved to the accident airplane’s stand. The aircraft arrived at 2138.

Shortly after the A319’s engines were shut down, the technicians checked integrated drive generator (IDG) oil levels. Following AMM procedures, Technician A went to the left engine, unlatched the inboard fan cowling door, and raised it high enough to see the IDG oil level indicator. He concluded the IDG needed oil. Technician A lowered the door to its hold-open position — one of five possible positions for the door/latch combination — but did not close or latch it. Technician B performed the same check on the right engine, and determined that it needed oil as well. He also lowered the door to the hold-open position and left it there.

The oil and a special gun to service the IDGs were not in the technicians’ service vehicle. While the IDG oil level inspection is part of all A320-family weekly checks, the oil rarely needs topping off, or “uplifting.” This, Technician A told the AAIB, is why the oil and oil gun were not routinely carried on overnight service vehicles, even when A320 weekly checks were on the schedule. (A BA analysis done as part of the investigation found that adding oil was needed on about 3 percent of A320-family weekly checks.)

The technicians decided to finish the rest of the accident airplane’s daily and weekly service, move on to other aircraft, and come back to the A319 later in the shift after obtaining the needed supplies. Technician A entered the airplane’s flight deck and completed a technical log entry for the daily check, marking the time at 2300. He then made an open entry for the weekly check, but did not make a required entry for the IDG work.

“If an IDG oil uplift was required, an open defect entry relating to the required uplift had to be entered in the technical log, and could only be closed and certified when the oil uplift had been completed, and the additional oil quantity determined,” AAIB said.

BA’s AMM did not require a separate entry to record the opening of fan cowling doors. But it did call for warning notices to be placed in the cockpit before doors are opened. No notices were placed in the cockpit.

“Such warning notices would have been seen by the flight crew … during their preparation for the flight and would have been considered abnormal, requiring follow-up action,” AAIB noted.

After their initial stop at the accident airplane, next on the technicians’ list was the A321’s daily and weekly checks. They then moved on to daily checks on another A319 and an A320. Following a break, the technicians collected a second vehicle and headed back to work.

During the break, Technician B checked the BA engineering materials stores near the break room in Terminal 5A, but could not find the needed IDG oil and gun. When the break ended, Technician B drove his vehicle to an ancillary stores location located on the other side of Terminal 5C to find the oil and gun. Technician A requested that they meet at the final aircraft of the night, an A320 on stand 509, on the same side of Terminal 5 as the accident airplane.

After completing the stand 509 A320’s daily check, the technicians set off for the accident airplane, with Technician A leading and Technician B following. But instead of stopping at stand 513, they proceeded to stand 517 and the A321 that had its weekly check.

Upon pulling up to the stand, the technicians did not verify the aircraft’s registration before attempting to complete the IDG servicing. When they found the fan cowling doors closed, they thought it was “strange,” the AAIB report said. But Technician B relayed an instance in which he took a break while working on an engine, only to find the cowling doors closed when he returned.

The technicians opened the A321’s fan cowling doors and double-checked the IDG oil. It did not need servicing. The technicians — still believing they were back at the accident airplane — reasoned that the engines had cooled in the three hours since their original check, allowing residual oil to drain back into the oil sump.

Concluding that their work was done, the technicians closed and latched the cowling doors on both engines, following required procedures. The aircraft’s technical log had been taken to an engineering office for a routine weekly administrative check, a task that was in line with the carrier’s Terminal 5 short-haul line maintenance procedures for weekly checks.

When they returned to the crew room, their tasks included completing the weekly check worksheet and technical log for the accident airplane. The technicians also relayed their story about finding the fan cowling doors closed and the change in oil levels. Nobody questioned whether the technicians had returned to the correct aircraft.

AAIB’s report identifies the technicians’ failure to follow the AMM, as noted, as one of the two causal factors in the accident. But BA recognized that many factors endemic to its procedures — or not accounted for in the procedures — set the stage for the technicians’ mistakes. In the months after the accident, BA made a concerted effort to change its system.

The most significant change was organizing line maintenance teams. “Through the recruitment of 26 additional staff, the line maintenance team structure has been altered to form individual teams” of [LMA], B1 and B2 staff “operating under the oversight of a maintenance supervisor,” the AAIB report explained. “Aircraft assigned for maintenance will be processed by a single team providing improved supervision and oversight of maintenance tasks.”

The carrier’s A320 line maintenance procedures have been updated to require open technical log entries whenever fan cowling doors have been opened. BA also has staggered IDG checks during weekly checks “to prevent the possibility of both sets of fan cowl doors having to be opened on any one occasion,” AAIB said.

BA also created special “wet” and “dry” kits especially for A320 daily and weekly checks. “The non-availability of equipment … nearby to [the accident airplane] may have played a role” in the technicians leaving the fan cowling doors open “by inciting the technicians to postpone completion of the work until they had an opportunity to collect the IDG gun from stores,” the AAIB report said. “The company’s vehicles have been modified to carry the kits and a replenishment process established to enable engineering staff to collect serviceable kits prior to commencing maintenance work,” the report said.

BA has taken steps to boost general awareness of aircraft undergoing line maintenance. It mandates that technicians performing line maintenance on any short-haul aircraft place a red card marked “AIRCRAFT IN MAINTENANCE” along with the aircraft’s registration on the flight deck pedestal. It also requires special gaiters, or high-visibility covers, to be placed over the nosewheel of any aircraft on which “there has been a break in an airworthiness-related task,” AAIB said. Each gaiter includes an identification number belonging to the maintenance team working on the aircraft.

During its probe, BA discovered that aircraft “swap errors” (mistakes in which maintenance personnel confuse one airplane for another) occasionally occurred during line maintenance, but these events were rarely reported. Several factors played a role here: the fact that the errors were considered routine and usually discovered before leading to any notable ramifications, and that BA’s occurrence reporting system did not have a category for tracking swap errors. In the case of the accident airplane, the fact that the same technicians were assigned to both aircraft removed the possibility that other workers assigned to service the other airplane would detect the errors.

“The low level of reporting of aircraft swap error events stemmed from these behaviors having become accepted as a ‘norm’ within the line maintenance operation,” AAIB noted. “As a result, there was limited opportunity to introduce mitigating actions.”

BA has added a category in its reporting scheme for recording aircraft swap errors.

AAIB noted that Technicians A and B had several opportunities to detect their swap error, but failed to follow proper procedures. Perhaps the greatest chance for them to catch their mistake — placing the technical logbooks in every aircraft with open tasks — was taken from them by BA’s logbook review practice. “This working practice inadvertently removed the main safety barrier for trapping the aircraft swap error, as it is probable that the error would have been discovered had the technicians attempted to sign for [the accident airplane’s] weekly check in [the other airplane’s] technical log on board the aircraft.” AAIB’s probe found different logbook protocols within BA, even at LHR. The short-haul line maintenance team was the only one that removed logbooks for administrative checks. BA now keeps technical logs in all aircraft during line maintenance activity.

BA’s application of lessons learned from the accident go beyond its procedures. The carrier’s human factors training has been updated to reflect what it gleaned from the occurrence and subsequent investigation.

The carrier also created an engineering safety culture team “to conduct on-the-job competence assessments of maintenance staff across all production areas on an unannounced, random basis,” the accident report said. “The assessment includes checking interpretation of procedures, observation of tasks accomplished and attitudes toward safety. Where areas of improvement are identified, the team will focus on improvement of procedures and supporting systems.”

Sean Broderick, a former editorial staff member of the American Association of Airport Executives and the civil aviation–maintenance, repair and overhaul team of Aviation Week & Space Technology magazine, is a freelance aviation journalist.

Note

- AAIB. “Report on the Accident to Airbus A319–131, G-EUOE; London Heathrow Airport; 24 May 2013.” Aircraft Accident Report 01/2015, July 2015.

Featured image: © London Heathrow Airport

Engine: © U.K. Air Accidents Investigation Branch

Airport scene: © London Heathrow Airport