Government and industry safety specialists within commercial air transport and business aviation have confronted a number of situations in recent years in which pilots reported low-altitude traffic conflicts with small unmanned aircraft systems (UAS). Among concerns have been sightings of UAS aircraft — unknown to air traffic controllers — operating higher than 400 ft above ground level (AGL), evasive maneuvers and near-midair collisions near airports (see “Opening the Skies”).

These specialists’ counterparts in the U.S. wildlands1 aviation firefighting community have welcomed opportunities to share parallel experiences and the defensive measures they have taken so far, as discussed in their reports, a public education campaign and an update briefing with AeroSafety World.

They are applying risk-analysis methods, tools and tactics through their safety management systems to discourage intrusions by UAS operators that repeatedly have forced suspension of aerial firefighting operations in the fire traffic control areas (FTCAs) of wildfires. Research by subject matter experts shows that wildfires larger than 50,000 acres (20,234 hectares) have increased since 1986, with the largest increase in quantity of wildfires occurring since 2003 and many recent large wildfires ranked as more intense than those in historical records.2

In this context, an Interagency Aviation Safety Alert to the wildlands aviation fire community in July 2014 said, “Increased unmanned aircraft activity presents hazards to all [wildlands fire] aviation users, including resource operations. Most commonly (but not exclusively), unmanned aircraft will be operating within close proximity to terrain, thus increasing risk for low-level resource operations. Resource operations including reconnaissance and aerial application with extremely limited reaction time usually operate without the protection a [U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) temporary flight restriction (TFR)] provides within most incident operations.”

National protocols3 direct air and ground wildland firefighters’ response to UAS intrusions, derived from a fundamental policy that states, “The protection of human life is the single overriding suppression priority. Setting priorities among protecting public communities and community infrastructure, other property and improvements, and natural and cultural resources will be done based on the values to be protected, public health and safety, and the costs of protection. Once people have been committed to an incident, these human resources become the highest value to be protected.”

Three shutdowns of aerial firefighters’ responses to major California wildfires in June and July 2015 — now believed to have involved five privately flown UAS aircraft — received extensive news media coverage, but such incidents are not entirely unprecedented. For example, the Aviation Safety Communiqué (SAFECOM) system <www.safecom.gov/search.asp> — a publicly accessible database shared by Department of Interior agencies and the Department of Agriculture’s Forest Service for wildfire safety education, safety research and operational risk management — contains reports of intrusions or related incidents by FAA–authorized civilian and military UAS aircraft, airplanes and helicopters operated by government agencies, and privately operated airplanes and helicopters.

Regardless of aircraft category, land management agencies’ basis for prohibiting such aircraft intrusions (and prosecuting offenders) is 43 Code of Federal Regulations, “Public Lands: Interior,” Part 9212.1, “Prohibited Acts,” which says, “Unless permitted in writing by the authorized officer, it is prohibited on the public lands to: … Resist or interfere with the efforts of firefighter(s) to extinguish a fire.”

Recent interagency strategy, intended first to persuade UAS operators not to intrude in FTCAs, has led to new policies and procedures; agency familiarization with the characteristics of popular small UAS (also called drones or remotely piloted aircraft) and the demographics of their operators; analysis of about 33 wildfire-intrusion incidents by operators of small UAS since January 2015; and a campaign to educate the public about this threat and UAS safety in general, says Jessica Gardetto, deputy chief, external affairs, U.S. Bureau of Land Management (BLM) National Fire and Aviation, and the National Interagency Fire Center.

“People maybe don’t realize at first exactly how dangerous it is to interfere with wildfire response. They think, ‘I’ve got this little device — how dangerous could it be?’ But even a small UAS being sucked into the rotor can cause a helicopter to go down. That would be a very severe situation and definitely an extreme safety issue,” she said.

Tightly Confined Airspace

Hazards are inherent because of concentrated aerial firefighting traffic in a confined area even before considering the threat created by an intruding drone.

“The world of wildfires is very complex, especially regarding air traffic,” Gardetto said. “In most wildfires, firefighting helicopters, small fixed-wing air tankers, large air tankers, air-attack planes and, sometimes, numerous other types of helicopters are working in different areas over a fire. A lot of these aircraft fly low. For example, helicopters are dropping water on the fire while flying hundreds of feet above the ground, which is the same level at which people fly UAS aircraft.

“Then you have someone who is trying get pictures of the wildfire. From what we have seen — assessing and working to try to determine who buys UAS and who flies them regularly — it’s a pretty broad demographic of people. Wildfires are interesting, and we understand that most operators don’t mean any harm. But they don’t know that flying UAS aircraft in the area is actually risking the lives of the pilots and the ground firefighters.”

The National Interagency Fire Center’s database received about 13 reports between January and late June 2016 of small UAS wildfire intrusions in the United States and Canada (see “UAS Intrusions in U.S. Wildfire Airspace in 2016”). In 2015, at least 20 such flights occurred over or near wildfires in California, Colorado, Oregon, Utah, Wyoming and Washington. During 2015, aerial firefighting operations in these states were temporarily shut down on at least 12 occasions, and two cases of near misses with drones occurred, Gardetto said.

Temporary Restrictions

Training of pilots to fly manned aircraft covers compliance with TFRs whenever issued, for various reasons, by FAA. “For a lot of wildfires, they will issue a TFR for the airspace over the fire. However, there’s not always a TFR in place largely because some fires haven’t been burning long enough to get through that process for submitting a request for a TFR. That’s why we’re asking people just to keep those devices as far away from fire as possible regardless of whether or not there’s a TFR in place,” she said.

What constitutes a safe distance from firefighting operations, for either manned aircraft pilots or small-UAS operators, is difficult to state exactly. “The aerial firefighting traffic over a fire can be coming from any or all directions,” Gardetto said. “If you’re a member of the public, you could be close enough to interfere, even though you’re not technically flying your device over the fire. If you’re anywhere near it, you still run the risk of your device colliding with some of the firefighting aircraft because they’re coming in and out of the fire. So we’re asking people, ‘If you see a fire, please do not launch your UAS even if you’re miles away, which is hard because people are curious. For the safety of pilots and firefighters, it’s just the best call.”

Regardless of TFR issuance, air traffic control (ATC) personnel and/or non-ATC airport staff anywhere near a wildfire typically advise pilots of manned aircraft through various standard modes of communication.

“In some cases, firefighting agencies are going to be flying tankers out of a nearby airport or flying within the airport’s airspace, so other pilots definitely will be made aware that we have fire traffic in the area,” she said. “Our air tankers, helicopters and air-attack planes are always being tracked by FAA air traffic controllers and our automatic flight tracking.” If information about aerial firefighting has not been received, the nearest ATC tower or other ATC facility typically is the best source to check, she said.

Similarly, information about extreme weather phenomena generated by wildfires, included in forecasts and current observations (ASW, 2/11), is readily available to pilots and UAS operators from standard aviation weather sources. “The National Weather Service puts out a fire weather warning to all weather services near the area and/or nationally so that they will know if there’s a large column of smoke in the area” or if they’re going to be expecting high winds, dry fuel and/or low relative humidity, Gardetto said.

Self-Preservation

The current UAS wildfire-intrusion safety campaign primarily focuses on threats to air and ground firefighters. This argument alone has persuaded some operators to state in internet forum posts that they are heeding the no-fly warnings, and to criticize fellow operators who argue that their photo/video missions cannot be harmful, for example, because they take precautions to avoid manned aircraft at wildfires. The campaign does not focus on the life-threatening risk to UAS operators.

“Although people want to get closer, a wildfire is actually quite a dangerous situation. So we ask the public, ‘If you see a wildfire, go the other direction.’ Fire can switch direction in a heartbeat — especially if they’re in an area experiencing high gusts of wind. You may think it’s moving away from you in that case, but the fire can easily overtake you before you know it.”

Mandatory Grounding

Situations described in the BLM database of wildfire UAS intrusions show standdowns of aerial firefighting per the national protocol. The protocol’s flow charts, checklists and decision points cover suspending aerial firefighting operations, diverting participating aircraft pilots to alternate areas, holding these aircraft at an alternate location and altitude, briefing ground crews and investigating the intrusion — until the air tactical group supervisor (ATGS) is confident that the intruder UAS aircraft has left the area and will not return to the area.

“If there is a UAS aircraft spotted in the area, we have to shut down all air traffic until we determine that the UAS is no longer a threat,” Gardetto said. “Unfortunately, in a lot of cases, if we have to shut down air operations, the fire can grow larger because we don’t have helicopters making water bucket drops and we don’t have air tankers making retardant drops, so it’s very detrimental to fire suppression overall.” Aircraft transporting an ATGS or surveillance crewmember are similarly affected, typically degrading the real-time intelligence from observers.

The unexpected interruptions of firefighting have many negative impacts for the pilots, not to mention ground firefighters. “Many different aircraft are coming in and out of the area constantly throughout the day,” she said. “Firefighters and pilots are already working in an extremely dangerous situation. To add an additional dangerous element is very frustrating to them.”

Campaign Update

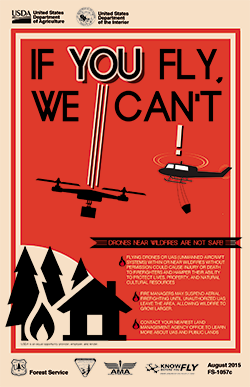

Since an ASW article (ASW, 10/15) first noted the UAS wildfire-intrusion campaign, officials have reviewed or updated a few aspects. The campaign by the Forest Service — called “If You Fly, We Can’t” — has expanded links to public awareness and educational materials, such as extensive multimedia content downloadable from the FAA website <www.faa.gov/uas>. Most importantly, FAA’s free smartphone application — called B4UFLY — has been released for public use.

“B4UFly is very useful if there is a TFR in an area because people can see it right away,” Gardetto said of UAS operators planning flights. “In many cases, they will use that to get their data updated. If there’s not a TFR issued for the wildfire, however, that’s going to be an issue.”

BLM National Fire and Aviation has been working more closely than last year to assist UAS manufacturers that already utilize wildfire TFR data from the FAA for built-in, no-fly geofencing restrictions in their UAS devices, such as DJI <www.dji.com/newsroom/news/dji-fly-safe-system>. Geofencing technology is promising and expected to become especially useful in protecting wildfire operations, Gardetto said.

Also important to the campaign are refinements to data collection and analysis by the aviation specialist at BLM National Fire and Aviation who now tracks UAS incursions using all the available data sources.

Within government agencies, BLM National Fire and Aviation also issues alerts called Safety Nets to the wildlands aviation firefighting community that consolidate facts from SAFECOMs and related internal analyses, Gardetto said, “The entire wildfire community culture has the aspect of people being able to freely report any safety issue at all, and not face any sort of repercussions or punishment — or even feel embarrassed about it.”

Online forums of UAS operators — some at risk of federal enforcement action by posting their UAS-generated footage of wildfires — interest the wildlands aviation firefighting community from the standpoint of gauging how best to reduce intrusions. So far, as noted, appeals to these groups’ shared interest in building a reputation for safely flying UAS and minimizing risk of harm to others have resonated, if the posts to forums are to be believed. Gardetto said the wildfire-related agencies assume typical small UAS operators will appreciate the issues and the seriousness of safety messages.

“We have had people agree strongly with our prohibition of UAS wildfire intrusions when we put things on social media. They make comments like, ‘I would never think to do that, but I can also see how someone might not realize that it’s a dangerous situation.’ But other commenters online are not always in support of the fact that it’s a safety issue.”

Notes

- In U.S. terminology, wildlands are natural forests, shrub lands, grasslands and other vegetation areas that have not been significantly modified by agriculture or human development. Wildland fire means any non-st”ructure fire that occurs in wildlands, including prescribed fires, which are planned ignitions by wildland fire authorities, and wildfires, which the National Wildfire Coordinating Group defines as “an unplanned ignition caused by lightning, volcanoes, unauthorized, and accidental human-caused actions and escaped prescribed fires.”

- Stein, Susan M.; Comas, Sara J.; Menakis, James P.; Carr, Mary A.; Stewart, Susan I.; Cleveland, Helene; Bramwell, Lincoln; and Radeloff, Volker C. Wildfire, Wildlands, and People: Understanding and Preparing for Wildfire in the Wildland-Urban Interface. Rocky Mountain Research Station, U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service. General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-299, January 2013.

- U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management, National Park Service, and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service. Interagency Standards for Fire and Fire Aviation Operations, NFES 2724, January 2016.

UAS Intrusions in U.S. Wildfire Airspace in 2016

The following excerpts of selected briefings about unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) flights, edited by ASW, are from a report titled 2016 UAS Airspace Situations Involving Land Management Agencies (Wildfire and Non-Wildfire Included), submitted June 27, 2016, by the U.S. Bureau of Land Management National Fire and Aviation to the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA):

Utah, June 19, 2016 — The structure group for the Aspen Wildfire located near Cedar City reported an intrusion into the temporary flight restriction (TFR) area and over the north end of the fire traffic area by a blue and white drone. Air operations were suspended for approximately four hours, then resumed to support fire line personnel. (Aviation Safety Communiqué [SAFECOM] 16-0370)

Utah, June 19, 2016 — Just after the air tactical group supervisor’s (ATGS’s) aircraft, called the air-attack platform, arrived at the Saddle Fire to assist in a fixed-wing retardant drop mission, a drone passed within 200 ft below and to the right. The platform was at 11,500 ft mean sea level (MSL) and no other firefighting aircraft were in the area. The air-attack pilot climbed, departed the fire traffic area, diverted to Cedar City and landed without incident. The ATGS also canceled missions of all the firefighting aircraft (three large air tankers and four single-engine air tankers, none yet en route) that had been ordered. (SAFECOM 16-0373)

Utah, June 20, 2016 — While performing bucket water-drop operations on the Saddle Fire at about 8,500 MSL, within an active TFR, the firefighting helicopter’s pilot and copilot witnessed a white and silver quadcopter flying past the right door roughly 100 ft below them. The ATGS and helibase managers shut down operations and grounded all aircraft for more than one hour while law enforcement officers searched for the UAS operator. (SAFECOM 16-0376)

Nevada, June 21, 2016 — The Washoe County Sheriff’s office reported that immediately after a helicopter pilot was released from a holding point 400 ft above ground level for the Hawken Fire near Reno, a small quadcopter drone passed under the nose of the helicopter. The drone missed the helicopter by approximately 50 ft (15 m). During the intrusion, the helicopter was inside the fire traffic area, within 1/4 mile (402 m) of the wildfire. No TFR was in effect. (SAFECOM 16-0385)

California, June 25, 2016 — While performing an air-attack mission as ATGS on the Reservoir Fire, we encountered a drone — a white-rotor quadcopter about 3 ft (0.9 m) square — flying over the fire at 1542 within the TFR. We were operating at 7,500 ft MSL, and the drone was approximately 500 ft below us. After a 30-minute tactical pause per UAS-intrusion procedures, and as we began to resume aircraft operations over the fire, we encountered the drone again at 1627. An airspace coordinator at the FAA air route traffic control center later reported that the UAS operator identified was an individual flying his quadcopter to photograph his burned home and his neighbor’s burned home for insurance purposes. (SAFECOM 16-0418)

— WR

Featured image: U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management