Citing a “significant lack of evidence” — including the failure to locate the main aircraft wreckage and flight recorders and the absence of voice and data transmissions — Malaysian accident investigators say they have been unable to determine why Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 departed from its planned route and vanished more than four years ago.

However, in the final report on the March 8, 2014, disappearance of the Boeing 777-200ER, The Malaysian ICAO Annex 13 Safety Investigation Team for MH370 said that, although it could not determine exactly what happened, investigators believe that the departure from the planned flight “likely resulted from manual inputs” — although it was impossible to identify the person who made those inputs, which directed the 777 over the southern Indian Ocean.

“Without the benefit of the examination of the aircraft wreckage and recorded flight data information, the investigation was unable to identify any plausible aircraft or systems failure mode that would lead to the observed systems deactivation, diversion from the filed flight plan route and the subsequent flight path taken by the aircraft,” said the 449-page report. “However, the same lack of evidence precluded the investigation from definitely eliminating that possibility. The possibility of intervention by a third party cannot be excluded either.”

“Without the benefit of the examination of the aircraft wreckage and recorded flight data information, the investigation was unable to identify any plausible aircraft or systems failure mode that would lead to the observed systems deactivation, diversion from the filed flight plan route and the subsequent flight path taken by the aircraft,” said the 449-page report. “However, the same lack of evidence precluded the investigation from definitely eliminating that possibility. The possibility of intervention by a third party cannot be excluded either.”

The report characterized the disappearance of Flight 370 and the lengthy search as “unprecedented in commercial aviation history,” and urged action to ensure that any similar event in the future will be recognized as quickly as possible, with procedures in place to track an aircraft that has departed from its filed flight plan.

Flight History

The accident flight began with a takeoff at 0040 local time from Kuala Lumpur International Airport. The 777 carried 227 passengers and 12 crewmembers on the flight, which was bound for Beijing. At 0043, a Kuala Lumpur Area Control Centre planner conferred with a Ho Chi Minh (Vietnam) controller, passing along word that the airplane was expected to arrive at waypoint IGARI at 0122.

At 0046, the airplane was transferred to Lumpur Radar and cleared within seconds to climb to Flight Level (FL) 250 (approximately 25,000 ft) and then to FL 350.

At 0119, an air traffic controller told the flight crew to contact the Ho Chi Minh Area Control Centre (HCM ACC), and the crew responded, “Good night Malaysian Three Seven Zero.” It was the last recorded radio transmission from MH370.

Radar showed that the airplane reached the IGARI waypoint at 0120, about one minute before the original estimated time of arrival, the report said.

The airplane’s Mode S transponder signal (an element of secondary surveillance radar or SSR) disappeared from civil and military radar around 0121; earlier, at 0107, the last transmission through the aircraft communication addressing and reporting system (ACARS) had occurred. Although ACARS reports normally are sent every 30 minutes, no subsequent reports were received

Sequence of events of disappearance of MH370.

Key

- Lumpur Tower cleared for takeoff at 0040:37 local time and MH370 departed at 0042.

- MH370 maintaining FL350 at 0101:17. MH370 reported again maintaining FL350 at 0107:56

- At 0119, 8.6 nm to waypoint IGARI, KL ACC instructed MH370 to contact HCM ACC. MH370 acknowledged with “Good Night Malaysian Three Seven Zero” at 0119:30.

- MH370 over waypoint IGARI at 0120:31.

- MH370 Mode S symbol dropped off at 0120:36.

- At 0121:13, 3.2 nm after passing IGARI, the radar symbol of MH370 dropped off.

At 0139, HCM ACC began contacting area control centers in Kuala Lumpur, Hong Kong and Cambodia to check on MH370’s whereabouts, but none of the units had established contact with the airplane.

The Kuala Lumpur Aeronautical Rescue Coordination Centre was activated at 0530, but there was no indication that HCM ACC took similar action with the Ho Chi Minh rescue center.

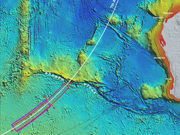

Diversion from planned route

ACARS = Aircraft communication addressing and reporting system

Key

- MH370 cleared for takeoff at 0040:37 local time and departed at 0042 local time.

- Last ACARS message 0107:29.

- Last secondary radar contact at 0120:36.

- Last military radar tracking at 0222:12.

Malaysian military radar continued to track the “blip” that represented MH370 until it disappeared at 0222, the report said, adding, “Even with the loss of SSR data, the military long-range air defence radar with primary surveillance radar (PSR) capabilities affirmed that it was MH370 based on its track behaviour, characteristics and constant/continuous track pattern/trend. Therefore, the military did not pursue to intercept the aircraft since it was ‘friendly’ and did not pose any threat to national airspace security, integrity and sovereignty.”

Satellite communications data indicate that the autopilot probably was functioning for more than seven hours, and the “inter-dependency of operation of the various aircraft systems” suggests that other elements of the airplane’s electrical power system also were available, the report said.

Changes in the airplane’s flight path after passing IGARI — “heading back across peninsular Malaysia, turning south of Penang to the northwest and a subsequent turn towards the southern Indian Ocean — probably resulted not from an aircraft system failure but from “the systems being manipulated,” the report said.

The report added that the investigation could not determine whether one of the pilots was flying, or if someone else was manipulating the controls.

Hired in 1981

The 53-year-old captain was hired by Malaysia Airlines in 1981, completed ab initio training and began flying as a second officer in 1983 and had accumulated 18,423 flight hours, including 8,659 hours in 777s; he had been a 777 captain since 1998 and was a type rating instructor and type rating examiner.

The captain had a flight simulator in his home that contained numerous default game coordinates, along with seven “manually programmed” waypoint coordinates (that is, waypoints that are not published in airway charts).

“When connected together, [these waypoints] will create a flight path from KLIA [Kuala Lumpur International Airport] to an area south of the Indian Ocean through the Andaman Sea,” the report said. However, the coordinates were stored in a file that saved information when the computer was idle for more than 15 minutes, and investigators could not determine if the waypoints came from one file or multiple files. The investigation found no data showing a route similar to that flown by MH370.

The first officer (FO), 27, completed cadet pilot training and was hired as a 737 second officer in 2008; he was promoted later that year to FO. He moved on to the 777-200 in 2013. He had 2,813 flight hours, including 39 hours in type.

The report said that, although there were no major disciplinary records involving the flight crew or cabin crew, “minor disciplinary issues” among the cabin crew had resulted in the issuance of cautionary administrative letters.

The captain’s “ability to handle stress at work and home” was characterized as good, with “no known history of apathy, anxiety or irritability,” the report said, and the FO was praised for his ability and “professional approach to work.” Neither had undergone any reported changes in behavior or lifestyle, the report said, and “there were no behavioural signs of social isolation, change in habits or interest, self-neglect, drug or alcohol abuse of the [captain], FO and the cabin crew.”

The investigation found “no evidence of irregularities” in the pilots’ capabilities or performance, their training or their scheduling, the report said, and “no evidence of anxiety or stress” in their communications with air traffic controllers.

No Mechanical Issues

The 777 was manufactured in 2002 and by March 7, 2014, had accumulated 53,472 airframe hours and 7,562 cycles. The engines were Rolls-Royce RB211 Trent 892B-17 engines, both manufactured in 2004. The left engine had 40,779 hours and 5,574 cycles, and the right engine had 40,046 hours and 5,508 cycles. No problems were found during turn-around checks before takeoff from Kuala Lumpur, and no ACARS maintenance messages were transmitted during the flight.

Maintenance records showed that the airplane was equipped and maintained in accordance with regulations and approved procedures, except for an expired battery on the flight data recorder’s underwater locating beacon.

The report said there was no indication of a mechanical problem with the airframe, engines, control systems or fuel.

“Although it cannot be conclusively ruled out that an aircraft or system malfunction was a cause, based on the limited evidence available, it is more likely that the loss of communication … prior to the diversion is due to the systems being manually turned off or power interrupted to them or … not used, whether with intent or otherwise,” the report said.

Although the airplane had four emergency locator transmitters (ELTs), the report said that “no relevant ELT beacon signals” were reported.

Several pieces of a 777 that were found on La Réunion Island and Mauritius were confirmed to have come from MH370, and other pieces of debris may have come from the airplane, but parts considered crucial to any investigation have not been recovered, the report said. Because some of the debris came from the cabin interior, investigators believe that the airplane broke apart, but they lack the information needed to determine whether the breakup occurred in the air or after striking the ocean surface, the report added.

Batteries and Fruit

During the investigation, questions arose about possible interactions between two items in a cargo hold — lithium ion batteries and mangosteens — and investigators attempted to determine if the water-soaked foam and juice extracts used in packing the tropical fruit could have come in contact with the batteries and resulted in a hazardous condition. “Highly improbable,” the report said, concluding that the combination could be hazardous only “if exposed to a certain extreme condition and over a long period of time.”

The batteries were not themselves classified as dangerous goods because they were packed according to guidelines, the report said. No other cargo was classified as dangerous, the report added.

ATC ‘Should Have Taken Action’

Operations at the Kuala Lumpur Air Traffic Services Center (KL ATSC) also were “normal with no significant observation” until MH370 was handed off to HCM ACC, which “did not notify the transferring unit (KL ATSC) when two-way communication was not established with MH370 within five minutes of the estimated time of the transfer of control point,” the report said.

“Likewise,” the report added, “KL ATSC should have taken action to contact HCM ACC [but] instead relied on position information of the aircraft provided by [Malaysia Airlines] Flight Operations. By this time, the aircraft had left the range of radars visible to the KL ATSC. … [A]bout one minute elapsed from the last transmission from MH370 and the SSR being lost from the radar display.”

Controllers in both centers failed to initiate required emergency actions and that failure delayed the start of search and rescue operations, the report said.

In the aftermath of the report’s release, Azharuddin Abdul Rahman, director general of civil aviation, submitted his resignation, saying, “While the report does not suggest that the accident is caused by the Department of Civil Aviation … nevertheless, there are some very apparent findings with regards to the operations of the Kuala Lumpur Air Traffic Control Centre.”

Recommended Improvements

The report urged changes to ensure that, in the future, any similar event “is identified as soon as possible and mechanisms are in place to track an aircraft that is not following its filed flight plan for any reason.”

The document noted the significant expenditure of funds and resources in searches for missing airplanes in recent years, citing, in addition to MH370, the June 1, 2009, disappearance of Air France Flight 447 while en route from Rio de Janeiro to Paris. The wreckage of the Airbus A330 was found nearly two years later by an underwater vessel searching the floor of the Atlantic Ocean.1

“In this technological epoch, the international aviation community needs to provide assurance to the travelling public that the location of current-generation commercial aircraft is always known,” the report said. “It is unacceptable to do otherwise.”

The accident investigation prompted a number of safety recommendations to address that point and eventually resulted in International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) action calling for autonomous transmission of positon information at least once a minute by an aircraft in distress, and for operators to establish tracking capability for airplanes throughout their areas of operations.

This article is based on Safety Investigation Report MH370/01/2018, “Malaysia Airlines Boeing B777-200ER (9M-MRO), 08 March 2014.” The report was written by the Malaysian ICAO Annex 13 Safety Investigation Team for MH370 and made public July 2, 2018.

Note

- French Bureau d’Enquêtes et d’Analyses (BEA). “Final Report on the Accident on 1st June 2009 to the Airbus A330-203, Registered F-CZCP, Operated by Air France, Flight AF 447, Rio de Janeiro–Paris.”

- The BEA traced the accident to the formation of ice crystals that obstructed the A330’s pitot tubes, causing air data sources to produce unreliable airspeed information. The crew’s incorrect response led to a stall from which the airplane did not recover. It plunged into the Atlantic, killing all 228 passengers and crew.

Featured image: © Rathke | iStockphoto

Accident aircraft: Laurent Errera | Wikimedia CC-BY-SA 2.0

Map 1: map background, TUBS | Wikimedia CC-BY-SA 3.0 modified by Susan Reed using information from the Malaysian ICAO Annex 13 Safety Investigation Team for MH370.

Map 2: map background, Andrew Heneen | Wikimedia CC-BY 3.0 modified by Susan Reed.

Flaperon: Malaysian ICAO Annex 13 Safety Investigation Team for MH370

Kuala Lumpur ATCC: WhisperToMe | Wikimedia CC0